Jan 17, 2017

Illustration by Al. Vaynshtayn, originally published in Kehos Kliger, Ikh un der yam (Buenos Aires, 1958)

INTRODUCTION

This reading guide is the second in a series designed to make our translations accessible for use by educators in a variety of settings.

For a PDF version of this teaching guide click here.

Introduction:

Yoysef Kerler’s poems “Old Fashioned” and “The Sea” (1979) grapple with themes of nature and history, personal and communal identity, and the shock and incongruity of living peacefully in a brutal world. Studying the historical and political context of these poems, their poetics, and the response to trauma that they convey will be instructive to students of modern Jewish history, poetry, and genocide studies, among other topics. This reading guide aims to direct instructors to resources that may be of use as they plan lectures, discussions, and classroom activities around Maia Evrona’s translation of these poems. It offers opportunities for instructors to gain the background knowledge that they might need to teach the text, and provides suggestions for using the text in a history or literature classroom.

Overview:

Yoysef Kerler (1918-2000) was a poet, lyricist, and literary editor born in Heysyn, in southern Ukraine (Podolye). He is considered one of the major Soviet Yiddish poets of the generation following Stalin’s death, and his poetry describes and emerges from his struggles as a member of a persecuted minority. 1 1 Though Kerler himself did not escape Stalinist oppression, he spent five years in the Vorkuta gulag. The biographical information in this teaching guide comes from Dov-Ber Kerler, “Kerler, Yoysef.” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2011).

Kerler’s life and writing reflect the tumultuous environment of Jewish life in the Soviet Union: hope for the blossoming of Yiddish culture that existed in the early years, the bloodshed and tragedy of war, and the anti-Semitism and authoritarianism of the postwar years.

In his early life, Kerler worked on a collective farm in northern Crimea, attended a Yiddish language technical school in Odessa, studied Yiddish literature and creative writing with Irme Drucker (1906-1982), and attended the Yiddish Drama School of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater, graduating in 1941.

After the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Kerler enlisted in the Red Army and was wounded in battle. Following a long recovery, he dedicated himself to writing and to activism on behalf of Yiddish. In 1947, Kerler moved to Birobidzhan, where he worked for the Birobidzhaner stern and protested the government’s policy to stop teaching Yiddish in the region. He returned to Moscow in 1948, and in April 1950 he was sentenced to 10 years of labor in the mines of Vorkuta for his “anti-Soviet nationalistic activity.” He was released in late 1955.

In the early post-Stalin years, Kerler worked as a lyricist, consultant and author of cabaret-style plays for Yiddish performers and wrote several popular songs. In 1965, he first applied for permission to immigrate to Israel, but while the permission was granted, it was later revoked and emigration appeared impossible. Kerler became one of the first refuseniks and wrote letters and articles that were smuggled to the West to shed light on the situation of Soviet Jewry. Risking further imprisonment, Kerler sent his protests and gulag poems to the New York Yiddish Daily Forward and the Yiddish literary magazine Di goldene keyt in Tel Aviv. The newspapers published his works at Kerler’s insistence, even though they feared for his fate.

In March 1971 Kerler finally left the Soviet Union and arrived in Israel, where he was awarded the Itzik Manger Prize for Yiddish Literature. Kerler worked to organize a Jerusalem branch of the Israeli Yiddish Writers and Journalists Association, edited several books and in 1973 founded the annual collection of literature and culture Yerusholaymer Almanakh (Jerusalem Almanac), which he edited and published until his passing.

Kerler’s first poems appeared in the newspaper Odeser arbeter in 1935. He published articles and poems in Eynikayt, the newspaper of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, during World War II, and his war poems appeared in his first book, Far mayn erd, (For My Land; 1944). In the Vorkuta gulag, Kerler was the only Yiddish poet to succeed in publishing his poems in Russian translation, camouflaged as “songs of the [Nazi] ghetto” in his second poetry collection, Vinogradnik moege otca (My Father’s Vineyard; 1957). Despite a near-impossible publication climate for Yiddish poetry, he published a second book of poems in Russian translation, Khochu byt’ dobrym (I Wish I Could be Kind; 1965). After his arrival in Israel, he published his first Israeli collections of Yiddish verse, Dos gezang tsvishn tseyn (Song through Clenched Teeth; 1971) and Zet ir dokh (Despite All Odds; 1972), centering on his Soviet experience. His later Israeli verse, published in Di ershte zibn yor (The First Seven Years; 1979), Himlshaft (Heaven Above; 1986) and Abi gezunt (For the Sake of Health; 1993) describe his new reality and echo with the memory of his Russian past. In the volume Shpigl ksav (Words in the Mirror; 1996), he published a selection of poems alongside those of his son, Dov-Ber, (pseud. Boris Karloff). His memoirs and critical essays on a selection of Soviet Yiddish writers are included in his books Der 12ter oygust 1952 (12 August 1952; 1977) and Geklibene proze (Prose Selections; 1991). His works have been translated into Russian, Chuvash, Hebrew, English, Spanish, Swedish, and French. Kerler’s last book is a Hebrew translation of his first Yiddish book published in Israel, Ha-Zemer ben ha-shinayim (Song through Clenched Teeth; 2000), translated by Ya‘akov Shofet. A posthumous collection of his poems, Davke itst—fun di letste un andere lider (Now Is the Time—New and Last Poems) appeared in 2005.

The poems in this selection may, on the surface, appear difficult to teach to students of Jewish literature or history. They do not contain the “documentary descriptiveness” favored by anthologists of Yiddish poetry who seek to “vivify a lost world” through the translation and transmission of poems. 2 2 Abraham Novershtern, “Review: Yiddish Poetry in a New Context.” Prooftexts 8, no. 3 (September 1988): 355-363. But while readers may not learn ethnographic details about the Jewish past in these poems, they can learn about the emotional history and experience of displacement and the memory of trauma.

Further, the poems and Kerler’s life story provide an interesting entry point for students to encounter Yiddish literature in three circumstances that are less commonly taught: Yiddish in the Soviet Union, Yiddish in Israel, and Yiddish after World War Two. While the Hebrew language and Jewish religious expression were largely suppressed throughout the Soviet period, Yiddish received strong state support in the first two decades after the Russian revolutions, and again for a brief period around World War Two. The fact that Kerler attended a technical college conducted in Yiddish and that he spent time in the Jewish autonomous region of Birobidzhan, where Yiddish was an official language, are just two examples of what state support meant for Yiddish in the Soviet Union. Even though many Jewish immigrants to Palestine and later to Israel were native Yiddish speakers, the Zionist nation-building project’s emphasis on Hebrew as the national language meant that people were discouraged from speaking Yiddish—sometimes violently so—especially in the early decades of the new state. Despite this, there was a small but active community of Yiddish writers in Israel, the best known among them being Avraham Sutzkever. Sutzkever, Kerler, and others continued to produce Yiddish literature and culture in Israel, and their work is an important reminder that Yiddish culture did not end with the Holocaust, but continued in Israel, Europe, the Americas, South Africa, and Australia, and continues today.

Classroom Activities:

- The Difficulties of Translation: In her introduction to the text, Maia Evrona discusses her struggles to translate the term kdoyshim. Ask students why they think the translator has felt it necessary to explain her choices regarding this word. Why is this word, in particular, so important in the poems? Ask students to consider Evrona’s explanation of the term and to argue for why they agree or disagree with how she has translated it. They may choose to offer some alternative possibilities for translating the term. You may also ask them if they can think of analogous words in English that would be difficult to translate to another language.

- Illustrating the Text: When publishing texts, the editors at In geveb must choose images to accompany the publication. These images suggest the editors’ interpretation of the poem and the context in which it should be read. Invite students to discuss the image that accompanies Kerler’s poem and how the editors have chosen to situate these poems through their choice of an image. Then, invite students to search for and suggest their own images (of nature, from historical archives, or even of their own creation) and explain how their image reflects their readings of the poems.

- What is Missing?: In each of these poems, the concrete reality of the poet’s present evokes feelings and memories from the poet’s past. Ask students to find moments that allude to this past and to speculate, based on the tone and language of the poem and on what they have learned about the poet’s life and context, about the “hidden” ideas and memories that the nature scenes convey (or that they obscure).

- What is Old Fashioned?: Break the class into three groups, and invite each to read a different stanza of “Old Fashioned.” Ask each group to write a definition of the word “old fashioned” based on the content of the stanza. When you bring the class back together and read the three definitions, ask the class how the definitions progress, and if and how the poem builds across the stanzas through new iterations of the term “old fashioned.”

- A Focus on Sound (For instructors who know Yiddish): Distribute the poems in Yiddish before you distribute the English. Read the poems aloud in Yiddish several times. Ask students to listen and make notes (on the Yiddish or separately) about what they hear: what tones of voice came across during the performance and when and where did a shift occur? What can they tell about the form of the poem from listening to it? For example, what repeated consonants did they hear? What rhymes or rhythms were apparent? What do they already know about what the poem conveys, even if they don’t understand the meaning of the words? Then distribute the English and ask students if, how, and where the translation was consistent with what they observed of the original.

- Compare and Contrast: Ask students to create Venn Diagrams comparing the two poems. Students should think about what they share and how they differ in terms of emotion, images, and sound.

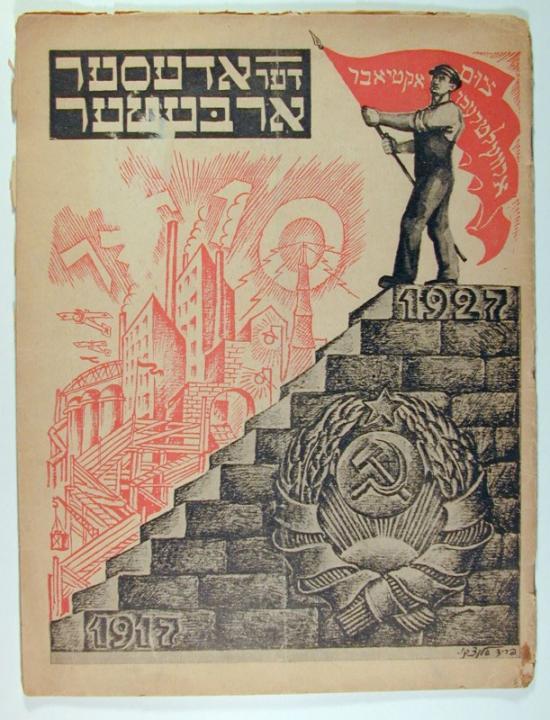

Kerler’s first poems appeared in the newspaper Odeser arbeter in 1935. Image via Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme.

Discussion Questions:

You may choose to ask these questions during class discussion, give them to your students alongside their reading to help them read and interpret the text, or assign them for reflection papers after your in-class discussion is complete.

Questions for “Old Fashioned”

- Who is the speaker in this poem?

- What word(s) characterize the emotion of the first stanza? Hopeful? Happy? Reassuring?

- What is the relationship between the sky and the satellites in this poem?

- What is the relationship between asphalt and the adjective “old fashioned”? How do you think the poet relates to the built environment in contrast to the natural environment?

- Does “old fashioned” exceed the span of an individual life?

- What is the relationship between the storm in the first stanza and the rainfall in the second?

- What is “old fashioned” about the newly born? Is this statement paradoxical?

- What is the relationship between the murdered Jews and the newly born? What claims does the poet make about the generation of murdered Jews through this comparison?

- How does the poet’s memory of the murdered Jews change over time?

- How does the poet himself change with age? To what extent is this a poem about aging?

- Does the poet represent his memory as reliable or stable?

- Describe the impact of the final line. Does it feel resilient? Defiant? Insistent? Redundant?

Questions for “The Sea”

- Is the quality of the sea of “today” exceptional in comparison with the sea throughout the century?

- How do you interpret the gender dynamics of this poem?

- What is the relationship between the “dazed century” and the “astonishment” of the sea? Are these parallel emotions, or are they different kinds of shock?

- What is the effect of the juxtaposition of the historical past (this past century) and the mythical past (Creation) in this poem?

Writing Prompts and Extension Activities:

These prompts are designed to direct students’ research and may be used for term papers or adapted for class discussions and activities.

- Taking Inspiration: Invite students to use Kerler’s poems as a model for their own writing. Students should take a scene from nature or from their own daily reality, and in describing it they should evoke a memory or idea that may be incongruous with the scene they are describing. Students should then write a short reflection on how their poem is inspired from, and how it differs from, Kerler’s writing.

- Translation Choices: During the translation process, Maia Evrona created two versions of the poem “The Sea.” She and the editors chose to publish one version, but she generously shared this other version with In geveb for the teaching guide. Ask students to reflect on the differences they see between these translations and how the choice of translation changes the meaning conveyed by the poem. Ask Yiddish readers to draw a comparison between each poem and the original. Students may also be asked to voice a preference for one translation or the other, and to justify that choice.

- Theories of Space and Time: Consider these poems alongside Jordan Finkin’s An Inch or Two of Time (2015). How do time and space intersect and interact in these poems? How do measurements of space like “great,” “thin,” and “infinite” reflect concepts of time like “old,” “newly born” and “memory”? In what ways are these poems representative of a diasporic sensibility?

- Comparative Poetry Assignment: Compare these poems with the poems of Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim in this article. 3 3 Z. K. Newman, “Rivka Basman Ben-Hayim: A Quiet Yiddish Israeli Voice” Midstream (Winter 2010): 13-16. How do these writers deal differently or similarly with the incongruities of past trauma and their present circumstances? How do their representations of nature compare?

- Comparative Poetry Assignment: Ask students to compare Kerler’s poems to these three poems by Avrom Sutzkever, also written in Yiddish in the late 1970s in Israel, and which also deal with images of water and ideas of memory (and were also translated by Maia Evrona).

- Thinking about Language: These poems come from the first collection of Yiddish poetry that Kerler wrote after immigrating to Israel, called “The First Seven Years” (Di ershte zibn yor), perhaps referring to the seven years he had at that point spent in Israel. Ask students to research and reflect on what it might have meant to write Yiddish poetry in Israel at that time. Why not Hebrew? Does this seem similar or different to Kerler’s choice to write in Yiddish in the Soviet Union; why not Russian? Ask students to read Avraham Sutzkever’s poem from 1948 “Yiddish”; are there common themes between this poem and “Old Fashioned”?

Suggestions for Further Reading:

The aim of this collection of articles is to help educators gain the context they might need to design lectures and lesson plans around the primary source document.

Dov-Ber Kerler, “Kerler, Yoysef.” YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe (2011).

Harriet Murav, Music From a Speeding Train: Jewish Literature in Post-Revolution Russia. Stanford University Press, 2011.

Murav explores Russian and Yiddish-language literature produced by Jews in the Soviet Union. She argues that before the 1930s Jewish writers used elements of Jewish traditions and motifs to question historical determinism about the future. When socialist realism forced Jewish writers to adapt to a new Soviet aesthetics, in which the shtetl (small town) represented the Jewish past and the urban factory or agrarian collective farm represented the future, Biblical tropes nevertheless appear in the Soviet Yiddish literary representation of a new promised land and challenge Soviet constructions of time and space. She writes about Soviet writers that called for revenge for the Holocaust in contrast with Western literary reflections of the Holocaust that tended to suppress urges for revenge, and she considers the notion of the writer as witness to the destruction of Jewish life during the Holocaust. She explains that postwar writers draw upon images of the Jewish past that had been destroyed.

Gennady Estraikh, “Literature versus Territory: Soviet Jewish Cultural Life in the 1950s.” East European Jewish Affairs, 33:1 (2003): 30-28

Estraikh describes the creation and context of post-Stalinist forums for Yiddish letters in the Soviet Union, and the Yiddish literati who participated in it. He discusses aborted plans for Yiddish publishing and theater, as well as Yiddish concerts and performances that were successfully undertaken in the context of an official Soviet effort to reduce Jewish cultural activities. He discusses the cultural activities surrounding Sholem Alechem’s yahrtzeits, as well as the publication of the periodical Sovetish heymland.

Shachar Pinsker, “Choosing Yiddish in Israel: Yung Yisroel between Home and Exile, Margins and Centers,” in Shiri Goren, Hannah Pressman and Lara Rabinovitch (eds.), Choosing Yiddish: Studies on Yiddish Literature, Culture, and History, (Detroit: Wayne State University, 2012), 277-294.

Pinsker tackles the complicated question of the role of Yiddish in Israel during the formative years of the state (1950s-1970s), examining the work and reception of the Yung Yisroel group of writers, who he argues were distinctively Israeli in their themes, images, representation of landscape and Yiddish literary language.

Jordan Finkin, An Inch or Two of Time: Time and Space in Jewish Modernisms. Penn State University Press, 2015.

This book examines interwar Yiddish and Hebrew poetry in order to argue that the metaphorical interaction of time and space is one of the innovative techniques of modern and modernist poetry, By using language to create time out of space and space out of time, poets imposed order on a world seemingly out of control.

Jeffry Mallow, “The Poetry of Yoysef Kerler,” Jewish Frontier (July–September 2002).

A collection of poems by Yoysef Kerler translated into English. These poems span a variety of political and personal themes, and evoke images from Russia and Jerusalem.

“The Black Sea” by Ivan Aivazovsky (1881) via The State Tretyakov Gallery

We’d like your feedback to make these guides as useful as possible. Please write to [email protected] to tell us what you found helpful, what needed clarification, what you would like to see more or less of, and what texts you would like us to produce guides for next.

If you are interested in creating a reading guide for a text on our site (independently or in collaboration with our pedagogy editor), or if you are already teaching with a text on our site and have ideas to share, please also write to [email protected].

Whether or not you are already teaching with texts published on In geveb, we are interested in sharing your strategies for teaching texts in translation with our readers. You can learn more about how In geveb readers are teaching with translations here. It’s not too late to tell us about your own teaching! We will publish additional thoughts in addenda to our Loyt di lerers post as readers write to us, and we are always looking for worksheets, reflections, and other resources: send them to [email protected].