Jun 05, 2019

Bais Yaakov students in Buczacz perform in a play called “Joseph and His Brothers.” Esther Wagner can be seen in the second row, fifth from the right. Esther Rivka Wagner (born Esther Willig) is the daughter of Rabbi Shraga Feivel Willig (b. 1870) and Sarah Chaya Blei (b. ca. 1890). Bais Yaakov students in Buczacz perform in a play called “Joseph and His Brothers.” Esther Wagner can be seen in the second row, fifth from the right. Esther Rivka Wagner (born Esther Willig) is the daughter of Rabbi Shraga Feivel Willig (b. 1870), the rabbi and mohel of the city, and Sarah Chaya Blei (b. ca. 1890). Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

INTRODUCTION

As the founder of Archive Transformed, a five-day collaborative residency hosted by CU Boulder, Chautauqua, and the Boulder Public Library that brings an artist and scholar together to “transform” archival material for the present and future, I had the pleasure of sitting down with the collaborators for one of the winning projects that is being incubated in May 2019 in Boulder, CO. Naomi Seidman, Chancellor Jackman Professor of the Humanities at the University of Toronto, and Basya Schechter, musician and founder of Pharoah’s Daughter, are working on their compelling project called The Bais Yaakov project.

Sarah Schenirer began the Bais Yaakov movement out of her apartment in Krakow in 1917 to address the lack of spiritual guidance for Orthodox Jewish girls and women. In 1919, the emerging school system received its name Bais Yaakov, making this the 100th anniversary of the movement. The Bais Yaakov had an unparalleled impact on a traditional Jewish society threatened by assimilation and modernity, educating a generation of girls to take an active part in their community. The movement grew at an astonishing pace, expanding to include high schools, teacher seminaries, summer programs, vocational schools, and youth movements, in Poland and beyond; it continues to flourish throughout the Jewish diaspora. In her recently published study, Seidman explores the Bais Yaakov movement through the tensions that characterized it, capturing its complexity as a revolution in the name of tradition.

Music was and still is a central component to building community in Bais Yaakov schools, and Seidman and Schechter are working to put out an album of Bais Yaakov music meant to transform the musical archive for the contemporary moment.

The Bais Yaakov project is underpinned by a website managed by Dainy Bernstein, currently a PhD candidate at CUNY Graduate Center. The website serves as a growing digital archive of resources about the Bais Yaakov movement. I sat down and spoke with Schechter and Seidman about the meaning of the musical component of the project, which is what they will be working on at Archive Transformed.David Shneer: The archive you are both working with is more or less being created as you do the project. What compelled you to bring together the stories, sounds, and images of the Bais Yaakov school system, founded by Sarah Schenirer as a school for Orthodox girls parallel to schools for Orthodox boys, and then to produce new work based on this archive?

Basya Schechter: Naomi contacted me to work musically with Bais Yaakov songs from pre-war Europe. For her I was a fit, because I myself had grown up in the Bais Yaakov world. I then left that community and became a musician. Whenever people ask what music school I went to, I tell them honestly that I didn’t go to music school, but my formative years in Bais Yaakov were in some strange way like a deep folk and traditional musical education. It was part of our daily culture to sit around during recess and sing together in harmonies, to get together late Shabbos at different friends’ houses, eat kokosh cake and sing shaleshudis songs. A natural sense of energy, pathos, and harmony emerged from those experiences. In the songs, one would find their place--whether it be the melody, high harmony, low harmony, counter melody. Even though there was a meld of voices, there was an opportunity in this meld to find your own creativity and expression in the group mind.

Since then, I have always wanted to do something with a “Bais Yaakov Choir.” There’s something in that format that was a “seal” of sorts, a certain way of singing, not reading charts or super careful singing, but full body, heart, voice, passion type singing. When Naomi, who knew me from the “ex-Orthodox creative world,” asked me to collaborate on this project, I knew immediately I wanted to form a choir--a choir made up of girls who all went to Orthodox girls’ schools inspired by the Sarah Schenirer movement. The material at this point is all pre-war Yiddish Bais Yaakov propaganda songs--the precursor of the songs from the 1960s to the 1990s. Those were the years that the members of this choir grew up in the Bais Yaakov movement.

Naomi Seidman: I spent a lot of time in archives writing the book about Sarah Schenirer, but once word got out that I was working on it, people started contacting me with various things they had in their families, and other material they had dug up themselves. So now I have a lot more documents and photos than I did when I was actually researching, and there was so much more than what I could use in the book. That’s part of what the website is about; it’s a way of sharing primary sources that are more than any one researcher can handle. And since it was so hard to find Orthodox archives or to get access to them as someone who is now considered an “outsider,” I wanted to make sure it was all open to all.

As for the musical part of the Bais Yaakov project, I was so inspired by what I saw Anna Shternshis do with Yiddish Glory [profiled here on In geveb], and by the work you, David, have been doing with Jewlia Eisenberg and others. And I recognized that what I had found in the archives was potentially so much easier to stage, since I found lyrics and music, not to mention documents about how the songs came to be (there was a contest in 1929 for a B’nos anthem, for instance). Add to that that Bais Yaakov still exists and flourishes, and the idea of reviving the musical repertoire of those early years was a gimme. Of course Basya Schechter was the obvious person to turn to, and when it turned out that she’d been dreaming for years about doing something Bais Yaakov-related, it just seemed so obvious. And getting this opportunity to spend real time together instead of the rushed few hours we’ve managed so far is a dream.

![<p><span class="dquo">“</span>Bais Yaakov Gezang” was written by Eliezer Schindler (<span class="numbers">1892</span>−<span class="numbers">1957</span>), one of the preeminent Orthodox Yiddish poets of interwar Europe. Born in Tyczyn, Poland, he lived in the Soviet Union before moving with his wife, Sali, to Munich, Germany, in the early <span class="numbers">1920</span>s. In <span class="numbers">1938</span> he emigrated to America and became a farmer near Lakewood, New Jersey. Greatly influenced by Nathan Birnbaum, he was an active supporter of and writer for the Olim [the <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>Ascenders”], the movement Birnbaum founded to revive Orthodoxy through communities of young Jews living <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>simple,” communal lives in rural and agricultural settings, devoted to traditional Jewish learning, language, art, music, and mystical piety and apart from the <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>pagan” and materialistic elements of modern urban life. Schindler’s poetry and essays, full of religious yearning, were particularly popular in the Bais Yaakov movement. This song appears in the Bais Yaakov songbook, <i>Undzer Gyzang: lider far bays-yakev shuln, basye farbandn, un bnos agudas yisroel organizatsiyes</i> (Lodz, <span class="numbers">1931</span>), <span class="numbers">2</span> – <span class="numbers">3</span>. Schindler worked with at least four composers, but this tune was probably set to music by Joshua Weisser. <span class="caps">NS</span>: Note: I am using Bais Yaakov’s own idiosyncratic transliteration (on the Polish side of the title page) for the title of the book.</p>](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ingeveb/images/gezang.png)

“Bais Yaakov Gezang” was written by Eliezer Schindler (1892−1957), one of the preeminent Orthodox Yiddish poets of interwar Europe. Born in Tyczyn, Poland, he lived in the Soviet Union before moving with his wife, Sali, to Munich, Germany, in the early 1920s. In 1938 he emigrated to America and became a farmer near Lakewood, New Jersey. Greatly influenced by Nathan Birnbaum, he was an active supporter of and writer for the Olim [the “Ascenders”], the movement Birnbaum founded to revive Orthodoxy through communities of young Jews living “simple,” communal lives in rural and agricultural settings, devoted to traditional Jewish learning, language, art, music, and mystical piety and apart from the “pagan” and materialistic elements of modern urban life. Schindler’s poetry and essays, full of religious yearning, were particularly popular in the Bais Yaakov movement. This song appears in the Bais Yaakov songbook, Undzer Gyzang: lider far bays-yakev shuln, basye farbandn, un bnos agudas yisroel organizatsiyes (Lodz, 1931), 2 – 3. Schindler worked with at least four composers, but this tune was probably set to music by Joshua Weisser. NS: Note: I am using Bais Yaakov’s own idiosyncratic transliteration (on the Polish side of the title page) for the title of the book.

DS: How will your project transform the archive?

BS: Adding a musical, performative element to a project is a way to breathe a three-dimensional experience into the stories and history that are part of the spoken, written, and visual presentation. These are songs that choirs sung back then, and we, as descendents of that movement, are reviving those songs, with the benefit of nearly a decade of work. Through this work, and possibly others writing on the evolution of this piece of the work, the Bais Yaakov archive itself will be added to.

NS: Bais Yaakov was a movement that brought religious passion into the lives of girls and young women, carrying them into a religious life through the force of shared singing, hiking, praying. Without feeling those things, even a little, it’s impossible to understand how it grew at such an enormous rate and how it managed to transform Orthodox life. And nothing helps you feel it like music. As for me, singing together with others who shared this formative experience, and who also left it, has been so powerful and deep. It’s made something about Bais Yaakov come alive for me again in a way that ten years of research didn’t manage to do.

DS: This is clearly a community building project about adult women, who grew up in the Bais Yaakov movement.

BS: At this early stage in our vision of what this project will become, we are mostly bringing women who have left the Bais Yaakov world together. There is a natural sisterhood forming between all of the singers in the choir, which makes it very much a community building project. Many of the group haven’t had a chance to sing as adults. There are so many organizations like Footsteps, which help ex-Orthodox men and women make transitions in their lives, and Cholent, which gives a space for creative expression and hanging out. This is a way for some of us women to gather and reconnect with some of the best experiences in our history, and remember the schools, camps, and challenging/joyful memories from that time period.

NS: It’s lonely being a scholar, as you know, David. And for me to have a project together with other people with whom I share so much is very precious. In academia we tend to be kind of independent contractors, working on our own resumés and careers. I’m married to a jazz musician, and I’ve always envied the collaborative part of his work life. It just seems so great to have part of the responsibility for making something and to have others contribute what they’re good at. To be able to hand songs that I was worried were simple or clichéd to Basya, and to see her turn them into things of beauty, and then to hear the choir make these songs their own, has been to witness the exponential powers of collaboration, and to feel enclosed in a community in a way that Bais Yaakov understood very well.

DS: What happens when the scholar and the artist have conflicts?

BS: For the most part we have a pretty aligned vision. But conflicts do happen, and we argue and process things out in the planning pretty quickly. Neither of us holds onto an unexpressed idea too long. We are both fairly immediate people, so things move quickly. Sometimes Naomi compromises, and at times I compromise. We each come so strongly from our own disciplines, or in my case lack of discipline, and there is a difference but we share a goal of connecting our stories/research/art--and we are both willing to try different things until we find the perfect balance. There’s something that I’m learning from the depth of information that is woven through the program. It also informs my performance life--research is good for all performance material.

NS: Our jobs are so different that I think it’s obvious who should have the final say on a particular issue, at least when it comes to things like how the music and performance should come together. Basya has also helped me see my own presentation style from the perspective of a performer rather than another academic, and I heartily recommend that other academics subject themselves to that kind of critique. The way we get away with boring our audiences to tears is really unforgivable. And Basya has such an ability to connect with audiences, to be real and in the moment and allow others to shine.

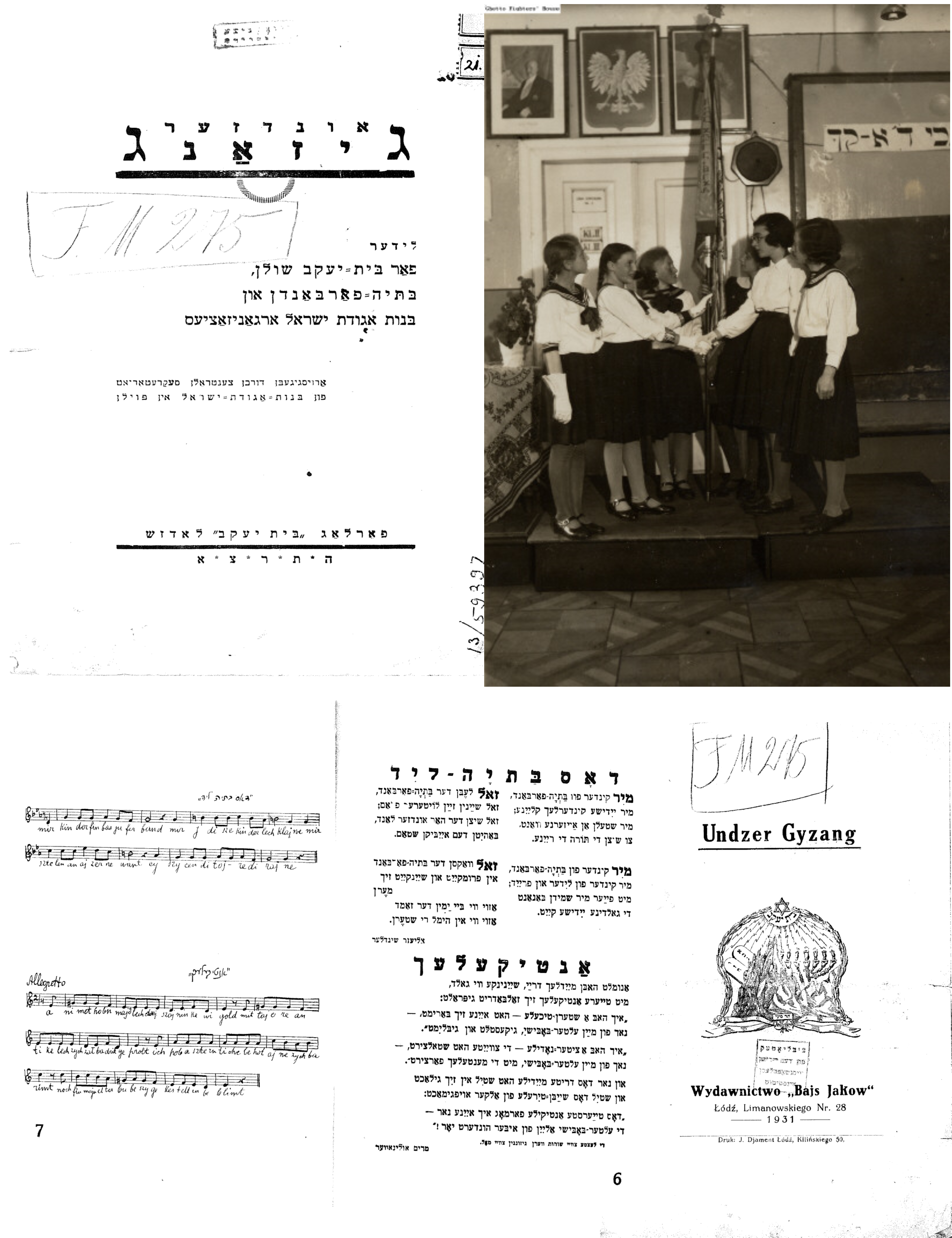

Cover and pp 6 – 7 of the Bais Yaakov songbook, with undated photo of girls raising the Polish flag in Lublin. Performance by pupils in a Bais Yaakov school, apparently in Lublin. Photograph by Ursus Foto in Lublin. Courtesy of the Ghetto Fighters House Archive. The two songs are “Dos Basya Lid,” by Eliezer Schindler, and “Antikelekh,” by Miriam Ulinover. Basya was the name of the youth movement for younger girls led and run by Bnos, the movement for girls from 15 – 18. “Antikelekh” is the title of a riddle-poem by Miriam Ulinover (1890−1944) published in her 1922 volume Der bobes oytser. Photo courtesy of Natalia Krynicka, Bibliotèque Medem, Paris.

DS: I’m interested in this notion of compromise as a way to collaborate. Can you talk more about a specific instance when either of you compromised as a way to push the project forward?

NS: One thing that’s come up is my tendency to want the songs to sound something like they did in 1931, and Basya’s tendency to make them new and her own.

DS: Jewlia Eisenberg, my musical collaborator, and I have the same dynamic, highlighting my desire to get the past “right” and her desire to bring the past into the present.

BS: I’m actually surprised, Naomi, at how excited you get when I bring a new musical element to the melody, or arrangement idea. I think for me, the conflict, or maybe not “conflict” per se but challenge, is when envisioning the album format: to expand the material or to keep it focused on the pre-war era.

NS: We’re clear that there’s an album in the future, but whether this album will be of interwar music or also of Bais Yaakov songs from the post-Holocaust era is something we’re still working through. I’ve also been super uptight about Yiddish pronunciation and consistency, and have come around to thinking that these songs were sung by girls with a wide range of Yiddish accents, and some for whom Yiddish was probably far from a native language. More generally, I’m letting go of the idea that I’m the “scholar” in ways that I think are changing my approach to research more generally.