Aug 25, 2015

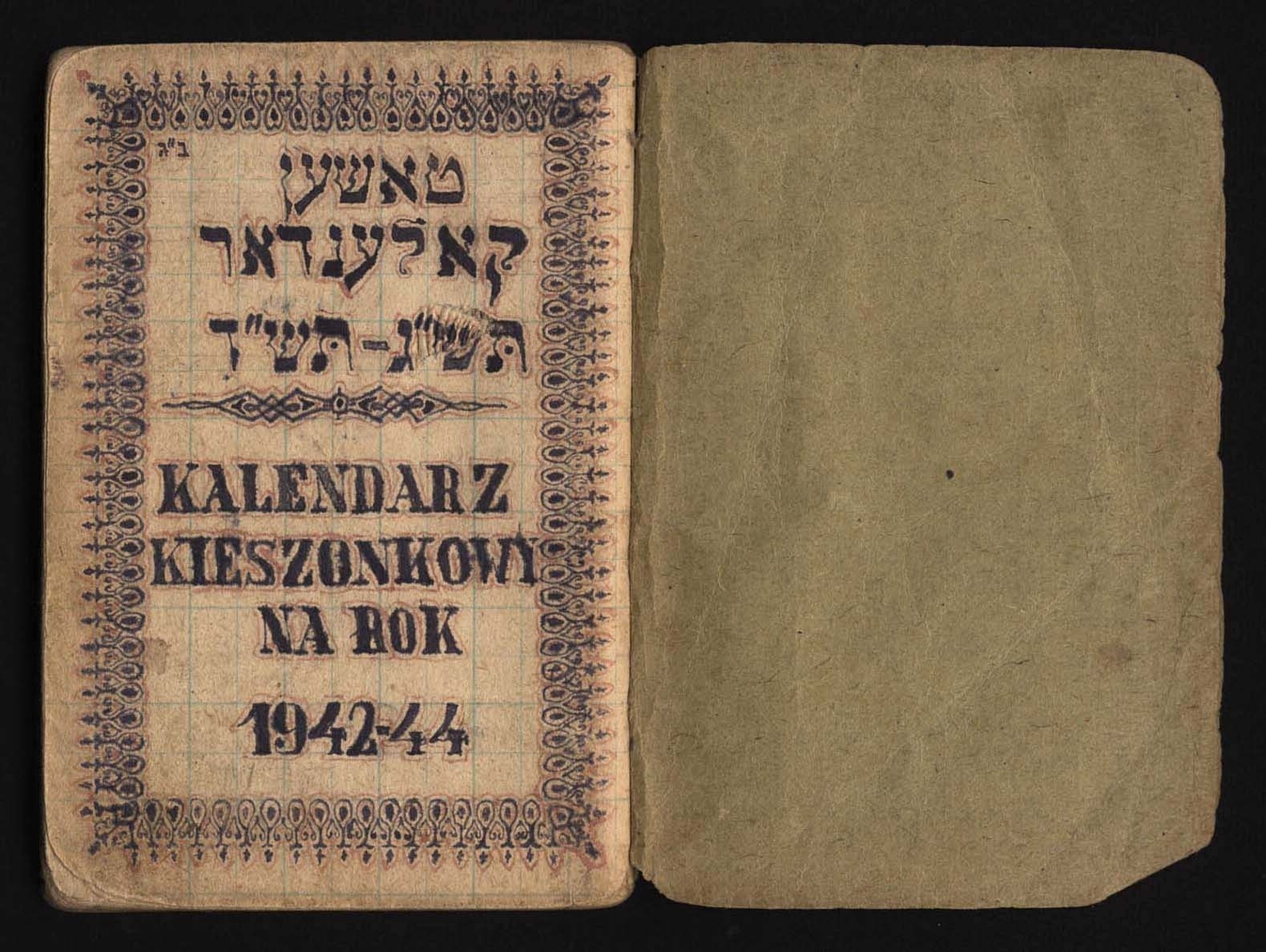

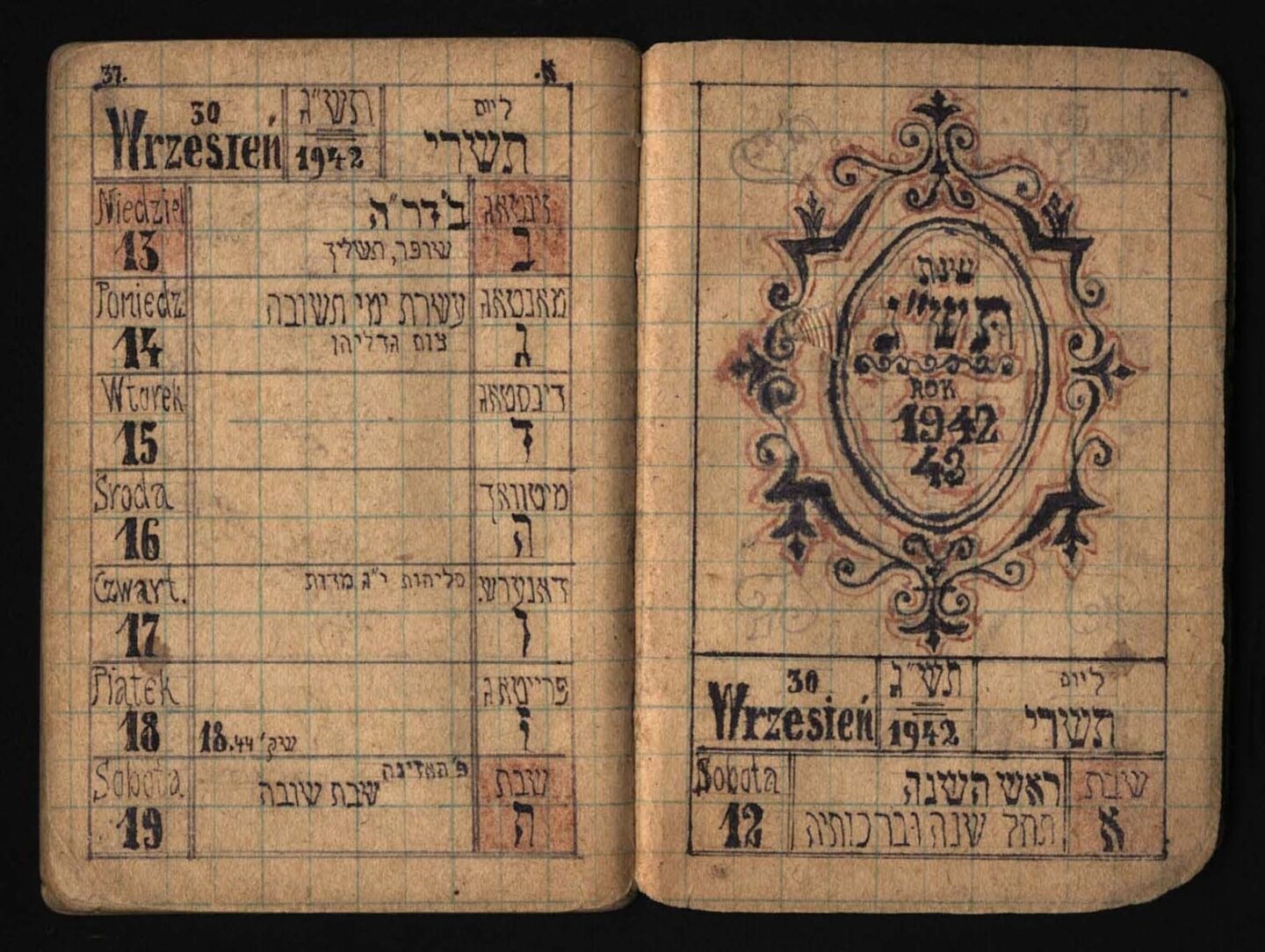

Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Scheiner’s magnificently calligraphed calendar for the Jewish year 5703, in Hebrew, Polish, and Yiddish.

ABSTRACT

Is there a special connection between the study of the Holocaust and the study of Yiddish? It seems obvious that study of the Holocaust would need to highlight Yiddish. But such has not been the case. The study of the Holocaust has often been pursued without the slightest nod to Yiddish. What is lost when Yiddish is left out?

I am not by training or vocation a Yiddishist. This means that the reflections that follow grow out of my study of the Holocaust rather than out of my study of Yiddish. It also means that my remarks may be relevant not only to those for whom Yiddish is central but also to those who, like myself, come at, or to, Yiddish in a more roundabout manner.

In light of my scholarly focus, I was asked to comment on whether I believed there is a special connection between the study of the Holocaust and the study of Yiddish. On the one hand, the connection seems obvious. The fury of the Holocaust tragically swept up a large swath of Eastern and Central European Yiddish speakers. Not only were huge numbers of lives and communities lost but the infrastructure of European Yiddish culture was decimated as well. Equally important was that much of the wartime Jewish response from these regions issued forth in Yiddish.

For both of these reasons, it would seem to be taken-for-granted that study of the Holocaust would need to highlight Yiddish. But such has not been the case. The study of the Holocaust has often been pursued without the slightest nod to Yiddish. The roots and history of this strange twist are too complex to review here in any detail. But reasons include 1) preferring the ostensible reliability of German documentation versus the subjective vagaries of victim testimony; and 2) having the study of the Holocaust fall under the rubric of European rather than Jewish history, with a corresponding emphasis on what were deemed to be relevant European (but not Jewish) languages. In this unfortunate calculus, Yiddish has secondary or tertiary importance at best when it comes to analysis and study of the Holocaust. This heartbreaking obliviousness has prompted numbers of rejoinders. A particularly shrewd one was Israel Knox’s preface to Jacob Glatstein’s 1968 Anthology of Holocaust Literature, which spelled out that a skewed view of Jewish response within the Holocaust stems from a lack of access to Yiddish-language sources. Nearly a half-century later, many researchers are still not aware that inattention to Yiddish carries weighty implications.

My trajectory has been the reverse. Though I might aim to study this or that topic on its own, Yiddish ends up being indispensable. My book Sounds of Defiance was ostensibly about the outsider position of the English language in relation to the Holocaust. Because English-language writing recognizes its own distance from the events, because it was a language of neither the perpetrators nor the victims, a certain honest ambivalence has until recently characterized Holocaust-related writing in English. In the epilogue, however, I note that the book was as much about Yiddish as about English, a claim I felt I could make because I couldn’t have chronicled the ambivalence of English-language writing on the Holocaust without the larger context of Yiddish’s insider position. Indeed, it has often been by way of association with Yiddish—for example, by posing as a translation from the Yiddish, or by speaking a broken English shot through with a Yiddish accent—that English-language Holocaust writing has endeavored to gain what legitimacy it could.

The same could be said for my next book, which dealt with Latvian-born psychologist David Boder’s 1946 interviews of displaced persons. Not every interview—not even most—was conducted in Yiddish. Indeed, Boder himself had facility in nine languages. But when he spoke during his project to a Parisian audience of European Jews, he chose Yiddish, because, as he put it, “I feel everyone should understand me.” In my current book project on Holocaust-era Jewish calendars, Yiddish usually plays an understated role. One finds, for instance, occasional columns of days named in Yiddish. This is the case, for instance, with the stark printed Jewish calendars circulated each year in the Łódz Ghetto, where Yiddish days complement the Hebrew months and the German headings—including at times a top-of-the-page banner, “Litzmannstadt,” the enemy’s name for the ghetto.

But the real payoff in such calendars comes between the lines: Rabbi Shlomo Yosef Scheiner’s magnificently calligraphed calendar for the Hebrew year 5703, rendered in hiding in wartime Poland, uses red-inked Yiddish insertions to record, on relevant dates, exactly who among his friends and neighbors was murdered where. To be sure, other languages figure importantly in setting out the calendar’s days, weeks, months, holidays, and fast days. Hebrew marks the Jewish months and festivals; Polish the Gregorian; and even Yiddish, in its semiofficial capacity as an essential folk tongue, is used to refer to the days of the week. That was all well and good, encompassing, as it were, the formal side of things, which gave the calendar all the components it needed to do the job calendars are meant to do—to track time, to distinguish between the sacred and mundane, to graphically lay out a future and provide the means for archiving the past. Even, or especially, while hiding in a bunker in wartime Poland in 1943. But the informal, improvisatory side of things—etching into a ledger the names of the murdered Jews—that, seemingly, had to have been done in Yiddish. Without attention to Yiddish, one would simply overlook the calendar’s true memorializing purpose.

Perhaps this rings true more generally. Without attention to Yiddish, one might ignore the reasons that can make study of the Holocaust, anguishing though it must certainly be, a profoundly worthwhile endeavor. These reasons include honoring Jewish wartime responses to their ordeal as authentically as possible. Reckoning with such vast intensive obliteration, scholarship on the Holocaust cannot help but memorialize—aim at retrieving from oblivion—the decimated lives and communities, many of which lay in the heartland of Yiddish-speaking Eastern and Central Europe. To efface Yiddish from the map of Holocaust Europe strangely adds to the oblivion rather than cuts through it. For when Yiddish disappears from the scene of Holocaust inquiry, so do Jewish voices, often, disappear as well.