Jun 23, 2020

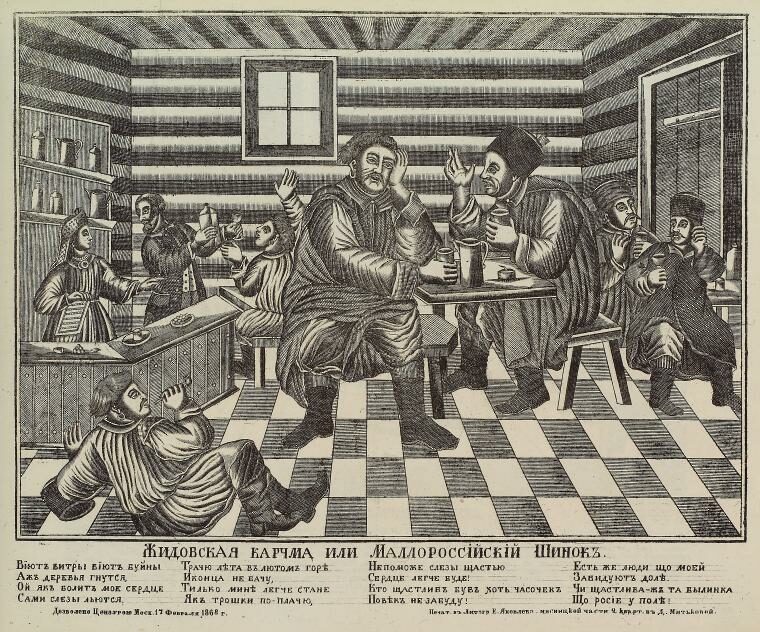

Scene inside a tavern, 1868. From the The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, New York Public Library. (NYPL digital collections)

ABSTRACT

This essay explores the ways in which the tavern and its urban-modern parallels function in the works of Sholem Aleichem. It argues that through his masterful, talkative Yiddish prose (or to use the term Roskies coined for Yiddish literature’s emulation of the spoken word: “Jewspeak”), he created a unique spatial setting that symbolically mitigated the shock of modernity for the Yiddish public.

For a pdf of this article click here.

Introduction

Taverns, and similar public gathering places, play various roles in the works of Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916). In Motl, the Cantor’s Son, the tavern is one of the stations that Motl and his family must endure on their way to America. In his novel Wandering Stars, the tavern is the place where the Jews of Vienna prefer to go to “gather for a beer, smoke cigars, and listen to someone singing…” rather than go to the Yiddish theater. 1 1 Sholem Aleichem, Blonzende shtern (New York: Hebrew Publishing Company, 1920), 198; trans. Wandering Stars (New York: Viking, 2009), 153. His early novel, Children’s Game, features a character with the traditionally Jewish occupation of tavern keeper. Also memorable is the amusing dialogue in The Letters of Menakhem-Mendl and Sheyne-Sheyndl involving the innkeeper of the most beautiful (and also the only) inn in Zhmerynka; in which Menakhem-Mendel’s dream of becoming a matchmaker is crushed.

Through the lens of Sholem Aleichem’s writings, this essay explores the ways in which the tavern, and its urban-modern parallels, function in his works. It argues that through his masterful, talkative Yiddish prose (or to use the term Roskies coined for Yiddish literature’s emulation of the spoken word: “Jewspeak” 2 2 Described by Roskies as “an essential expression of the once-living folk.” See David G. Roskies, “Call It Jewspeak: On the Evolution of Speech in Modern Yiddish Writing,” Poetics Today 35, no. 3 (2014): 238-250. ), he created a unique spatial setting that symbolically mitigated the shock of modernity for the Yiddish public.

The tavern, a public drinking space, fundamentally challenges core familial and religious institutions, rendering it a threat to the main ingredients that constitute Jewish identity. While drinking inside the Jewish home is an integral part of the religious ritual, drinking at the tavern can be a gateway to sexual permissiveness and revolutionary politics. Sholem Aleichem used the tavern in his writings as a spatial literary device that juxtaposed traditional and modern sets of ideas and behaviors. This space corresponds with the way Shachar Pinsker used Edward Soja’s term “thirdspace” to analyze the role of cafés in the creation of modern Jewish culture. If the café is the “quintessential modern diasporic Jewish space… a thirdspace that mediates between reality and imagination, inside and outside, past and present… without the false promise of homecoming”

3

3

Shachar Pinsker, A Rich Brew: How cafés created modern Jewish culture (New York: NYU Press, 2018), 310.

– then the tavern world offers all that plus a carnivalesque atmosphere. If the traditional Jews in the small Jewish town in Sholem Aleichem’s work “experience the transcendent power of Jewish myth” through the holiday cycle and its rituals, then for him it was there and then that “the carnival aspect of life broke.”

4

4

David G Roskies, A Bridge of Longing: The Lost Art of Yiddish Storytelling (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995), 167.

In contrast, the modernizing Jew, who abandoned those traditional rituals, regains in the tavern and its parallels a new set of experiences to replace them.

How do people talk about and within taverns in Sholem Aleichem’s works? Who frequents the tavern? Who runs the tavern? What is their relationship to one another? How do Sholem Aleichem’s taverns function compared to representations of taverns in other examples of Jewish and non-Jewish literatures? This essay argues that the tavern space plays a central role in Sholem Aleichem’s works by the dynamic ways in which it encapsulates the chaos and insanity of modernity.

The Tavern in Literature

The tavern commonly appears as a setting in literature. According to a recent anthology of drinking in literature, the tavern is a: “center of communal gathering; rival of home and church; male sanctuary from wife and children; corruptor of youth; site of sexual adventure; shelter for poverty-stricken; revolutionary breeding-ground; and political club.” 5 5 Nicholas O. Warner, In Vino Veritas: an Anthology of Drinking in Literature (Jefferson: McFarland & Co., 2012), 19. One can find contrasting literary representations of the cultural and moral benefits of the tavern in society. English poet William Blake praised the tavern in “The Little Vagabond” (1794) for its cheerfulness and welcoming atmosphere, contrasting it to the cold, oppressive atmosphere of the church. He wrote: “Dear Mother, dear Mother, the Church is cold,\ But the Ale-house is healthy & pleasant and warm;\... if at the Church they would give us some Ale…\ Then the Parson might preach & drink & sing,\ And we’d be happy as birds in the spring…”. Charles Dickens, on the other hand, condemned the taverns for their negative effects on the community in “Gin-Shops” (1836): “The gin-shops in and near Drury-Lane, Holborn, St. Giles’s, Covent-garden, and Clare-market, are the handsomest in London. There is more of filth and squalid misery near those great thorough-fares than in any part of this mighty city.” 6 6 Both quotes in: ibid, 92-127.

In Eastern-Europe, for centuries before Sholem Aleichem was born, Jews traditionally held positions of tavern keepers.

The Russian-Ukrainian writer Nikolai Gogol, was one of the main literary influences on Sholem Aleichem. 8 8 Roskies, Bridge of Longing, 153-156. In his story “Viy” (1835), Gogol gives the following description of a ‘Jewish tavern’:

Despite the hot July day, everybody got out of the wagon and went into the low, dingy room where the Jew tavern keeper rushed with signs of joy to welcome his old acquaintances. Under his coat skirts the Jew brought several pork sausages and, having placed them on the table immediately turned away from this Talmud-forbidden fruit. They all settled around the table. A clay mug appeared in front of each guest… [S]ince people in Little Russia, once they got a bit merry, are sure to start kissing each other or weeping, the whole place was soon filled with kissing… 9 9 Nikolai Gogol, The Collected Tales of Nikolai Gogol (New York: Vintage Classics, 2011), 168-169. “Little Russia” is an old name for the Ukraine.

In this spatial setting of a “low, dingy room,” we meet the Jewish tavern keeper. He is well-known in the region – he has “old acquaintances” who he welcomes with “joy” at his establishment. He runs his business well, with prompt service. However, his Jewish distinctiveness is clear both to him and to his non-Jewish customers. For him there looms the danger of consuming the non-kosher foods he provides to his customers, described here as “Talmud-forbidden fruit.” Another danger is sexual temptation: drinking is expected to make the place “merry” and “filled with kissing.” For his clients, who include Cossacks and a Christian theologian on his way to combat a pagan witch, but no Jews, he never ceases to be the other, referred to by his customers as the “the Jew.” 10 10 The Jewish tavern keeper also appears in Ukrainian songs as the object of hostility, the cause of peasant impoverishment. See Robert A Rothstein, “ ‘Geyt a yid in shenkl arayn’: Yiddish Songs of Drunkenness,” The Field of Yiddish: Studies in Language, Folklore, and Literature, Fifth Collection, ed. David Goldberg (1993): 245.

Speaking about the Tavern in Modern Jewish Literature

From its earliest stages, we find depictions of the tavern space in modern Jewish literature. Drinking and taverns played a prominent role in Hasidic literature, since its founder and the protagonist of many of its stories, the Besht, was himself once a tavern keeper. 11 11 Dynner, Yankel’s Tavern: Jews, Liquor, and Life in the Kingdom of Poland, 39. We also find it in Joseph Perl’s anti-Hasidic epistolary satire, The Revealer of Secrets (1819), written in both Hebrew and Yiddish. The tavern here functions as another tool in Perl’s arsenal to prove the debauched and corrupted nature of the Hasidim. It is part of their terrain. In letter 14, the Hasidic protagonist reports of an attempt to conceal the identity of the melamed (teacher) who helped the Hasidim cover their tracks in order to hide from the landlord (the porets), after they tried to steal an anti-Hasidic book from him. The landlord’s servant, recognizing the melamed, is persuaded by a friend of the Hasidim to go to a “shenk hoyz” (tavern house) run by another Hasid, the “shenkir,” who “gave them fish and a few glasses of mead. They ate and drank to their heart’s content, and while the servant was drinking, the melamed fled to the cellar and from the cellar to the outside.” After the servant noticed the escape, the tavern keeper gave him two rubles from the charity box (“the alms box of Rabbi Meyer Balanes”) to keep him quiet. The Hasidim also assumed the servant wouldn’t talk out of fear his master would find out that he was drinking in a tavern while he should have been fulfilling his duties. 12 12 Dov Taylor, Joseph Perl’s Revealer of Secrets:The First Hebrew Novel (Boulder, CO, 1997), 40-41; see also Letter 5 in which Perl mocks Hasidim for their excessive drinking (ibid, 29). For the original text see Joseph Perl, Sefer Megale Temirin, 1-2, critically edited and introduced by Jonatan Meir, with an afterword by Dan Miron (Jerusalem: Mossad Bialik, 2013).

The common stereotype held by Eastern-European Jews of the gentile working man who comes home drunk and is violent towards his wife appears throughout modern Yiddish and Hebrew literature, from Peretz to Bialik and beyond. For example, Bialik’s Hebrew poem “Jacob and Esau” (1922), itself an adaptation of a popular Yiddish song “Geyt a goy in shenkl arayn,” includes stanzas that alternate between negative depictions of the drunken goy (“To drink he must\ For that what makes him a goy”) and the pious Jew (“Wakes up early to pray\ Gives his creator praise and glory.”).

13

13

See: Hayim Nahman Bialik, Ha-Shirim, ed. Avner Holtzman (Or Yehudah, lsr., 2004), 437. About Yiddish songs of drunkenness, which often include ”drunken Jews,“ see Rothstein, “ ‘Geyt a yid in shenkl arayn’: Yiddish Songs of Drunkenness,” 243-62; and in Z. Skuditski Folklor-lider: naye materialn-zamlung (Folklore Songs: New Collection of Materials), vol. 2 (Moscow: Ernes, 1936), 259-270.

Bialik, whose father ran a tavern, very sharply contrasted the piety of his father to the piggish drunkenness of his customers in his poem “Avi” (“My Father,” 1928):

Between the pure gate and the tainted shuttled the cycle of my days,\ the sacred wallowed in the gross, and innocence in squalor,\ In the cave of human swine, amidst the foul pollution of the tavern,\ through vapors of detested draught, and sickening mists of smoke,\ behind the casks of liquor, above his yellow-parchment book\ appeared to me my father’s face, the skull of the martyr\…\ around us roared the drunkards and the gluttons splurged in their vomit,\ monsters with leprous faces and streams of defiling tongues… 14 14 Bernhard Frank, Modern Hebrew Poetry (Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1980), 5-7.

The bitingly sharp distinctions that Bialik drew between his pious Jewish tavern keeper father and his non-Jewish clientele are consistent with his Jewish-separatist, Zionist commitments, which Sholem Aleichem shared in theory but not in his finest art. Amongst Jewish-socialist writers, we can also find the detesting, social-moralistic attitude towards the tavern as the pinnacle of spatial corruption. These views appear most vividly in I. L. Peretz’s anti-capitalist Yiddish poem “Meyn nisht” (“Do Not Think”; 1906). In its first stanza, the tavern serves as a metaphor for the corrupt and unequal economic system. The speaker repeatedly warns the haves in the aftermath of the failed 1905 revolution that their judgment day is yet to come:

מיין נישט, די װעלט איז אַ קרעטשמע -

באַשאַפֿן צו מאַכן אַ װעג זיך מיט פֿויסטן און נעגל

צום שענק־פֿאַס, און פֿרעסן און זויפֿן, װען אַנדערע

קוקן פֿון װײַטן מיט גלעזערנע אויגן

פֿאַרחלושט, און שלינגען דאָס שפּײַעכץ און ציען צוזאַמען דעם מאָגן, װאָס װאַרפֿט זיך אין קרעמפֿן!

אָ, מײן נישט די װעלט איז אַ קרעטשמע!

Do not think the world is a tavern –\ Created so you can make a way for yourself with your fists and your nails\ To the tavern-barrel, and gorge and booze, when others\ Are looking from afar with glassy eyes,\ Fainting, and swallowing their spit and pulling together their bellies, quivering with cramps!\ Oh, do not think the world is a tavern!

The repeated warning in this poem “Do not think the world is…” appears in each of its three stanzas, where each time the noun changes between “tavern,” “stock market,” and “lawlessness.”

Enchanted Inns and the Fall of the Small Jewish Town

Taverns play a pivotal role in one of Sholem Aleichem’s best-known stories, “Der ferkishefter shnayder” (“The Enchanted Tailor”; 1900). In the story, an impoverished tailor, who bears the unusual name Shimen-Eli Shma-Kolenu (in Hebrew the first part means “hear [or be heard] my God,” second part means “hear our voice”), is sent by his bossy wife Tzipe-Beyle-Reyze to the neighboring town to buy a goat. His small hometown of Zlodiyevke (a recurring place name in other stories by Sholem Aleichem), and its surrounding grotesquely-named towns like Khaplapovitsh (khaplap means haphazardly), and Kozodoyevke (the neighboring town he is headed to; kozo literarily means “goat”), are all part of a fantastical Ukrainian geography created by Sholem Aleichem as part of what David Roskies termed a stylized folk narrative. 15 15 Roskies, Bridge of Longing, 160-167.

Shimen-Eli is a comical figure, expressed by his speech which is full of misquotations and twisted expressions. 16 16 Roskies, “Call It Jewspeak: On the Evolution of Speech in Modern Yiddish Writing,” 248-250. He is no world traveler. Leaving his familiar shtetl space for the next town to get the goat is a novel experience for him. On the way, he has to withstand the dangers of the chaotic outdoors. He meets his biggest challenge on his journey when he stops at his cousin Dodi’s tavern. This tavern is introduced in the beginning of chapter three as follows:

באמצע הדרך - פּונקט אין דער מיט װעג, צװישן די צװײ שטעט זלאָדײעװקע און קאָזאָדאָיִעװקע, שטײט אַ פֿעלד־קרעטשמע, װאָס מע רופֿט זי „די דעמבענע.“ די דאָזיקע קרעטשמע האָט אין זיך אַ כּוח, עפּעס נאָר אַ מאַגנעט, װאָס זי ציט צו זיך אַלע בעלי־עגלות מיט אַלע פּאַרשױנען, סײַ די װאָס פֿאָרן פֿון זלאָדײעװקע קײן קאָזאָדאָיִעװקע, סײַ די װאָס פֿאָרן פֿון קאָזאָדאָיִעװקע - מע מוז זיך אָפּשטעלן אין דער „דעמבענער“ כאָטש אױף עטלעכע מינוט! קײנער װײס ניט דעם סוד דערפֿון נאָר עד היום. אַ טײל זאָגן, אַז ס׳איז דערפֿאַר, װײַל דער בעל־הבית פֿון דער קרעטשמע, דאָדי דער רענדאַר, איז זײער אַ ליבלעכער פּאַרשױן און אַ גרױסער מכניס־אורח, דאָס הײסט, פֿאַר געלט האָט איר געקאָנט קריגן דאָרטן תּמיד אַ רעכט גלעזל משך מיט די שענסטע פֿאַרבײַסנס.

Midway along the road – exactly halfway between Zlodeyevke and Kozodoyevke, there was a rustic inn called the Oak Tavern. And this tavern excreted an irresistible force. It was a magnet, drawing on all the draymen and all the travelers going from one shtetl to the other. You just had to stop at the Oak Tavern, if only for a minute or two! This mystery has never been solved. Some people say that Dodi, the tavernkeeper, was a very charming and hospitable man – if you had the money, that is, you could get a proper schnapps and the finest snacks. 17 17 Translation taken from Joachim Neugroschel, The Dybbuk and the Yiddish Imagination: A Haunted Reader (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000), 189-190. The original can be found in Sholem Aleichem, Ale verk fun Sholem Aleykhem, Vol. 9-10 (New York: Folks-Fond, 1927), 9-68. All other Sholem Aleichem stories discussed in this essay are from the Folks-Fond edition.

This tavern, a country inn located midway between the twin shtetls, mystically attracts travelers from town to town. There are hints of the dubious businesses Dodi does on the side that provide him with extra income beyond what he earns from running a successful inn: “[He] never deal[s] with stolen goods themselves, but seems awfully chummy with all the infamous robbers” (idem). Dodi is wealthier than his cousin, a situation which contributes to the social-economic confrontation that drives the plot, and, as Dan Miron points out, eventually leads to Shimen-Eli’s mental devastation and death.

After their first interaction, Dodi decides to take revenge on his cousin for taunting him for being an unlearned Jew. He tricks Shimen-Eli by secretly replacing the she-goat for a billy goat and vice versa in each of the three visits the tailor pays him during his trips. The tailor’s stupidity and his affection for drink make it easier for Dodi to prank him. Sholem Aleichem was borrowing common stereotypes from Polish literature that represented the tavern keeper as possessing devilish characteristics, being fond of trickery, with his tavern located “at the edge of a boundary.” 18 18 See Opalski, The Jewish Tavern-Keeper, 11-15; and Horvath, “The Tavern As a Place of Communication in Hungarian Jewish Literature,” 282-283.

Like Sholem Aleichem’s most famous character, Tevye, Dodi’s location in the countryside amongst non-Jews rather than in the “Jewish” shtetl, metaphorically means confronting a modern-urban set of issues and conflicts. Dodi is a rich and “connected” urbanite compared to the poverty stricken, unworldly shtetl dwellers. Sholem Aleichem deals with this set of modern issues through the stylized folksy setting that is so essential to the esthetic pleasure a reader derives from the text.

Dodi is thus parallel to the acculturated urban Jew, who is unlearned in Jewish affairs, but materially rich. Roskies termed Dodi “the most demonic character in Sholem Aleichem’s storytelling corpus,” because of his big, hairy ogre-like physical appearance, and him being a prankster. 19 19 Roskies, Bridge of Longing, 167. But it is doubtful whether Dodi is more devilish than the New-York business-man Mr. Baraban, the narrator of “A Story with a Greenhorn” (1916). In a righteous tone, Baraban tells a gruesome story of how he cheated a new immigrant out of his pretty wife and fortune. At least Dodi had a sympathetic motive for his actions (paying back the tailor for his insults) rather than being motivated by sheer greed and envy.

In the story, Dodi is paralleled to Hodel the Excise Lady, who runs a tavern in Zlodiyevke (termed “shenkel,” a small tavern, as opposed to Dodi’s “kretshme”). Like Dodi, she is also a connected figure, though she is connected to government officials and to the working people of the town rather than to the underworld. Her place serves as a working-class meeting ground, where class struggles are played out. We meet her at a later stage in the story (chapter 10), when Shimen-Eli, trying to cope with his goat-crisis, goes to her tavern to drown his troubles with schnapps and to seek advice.

Hodel tells him a parallel version of his escaping-goat affairs, involving her aunt Perl trying to get hold of an allusive ball of cotton. Her tavern enhances the sexual drama at the core of the story, which includes many male\female contrasts: he-goat\she goat, Shimen-Eli\Tzipe-Beyle-Reyze, etc. Shimen-Eli dismisses her story by misquoting the Talmudic verse “nashim da’atan kala” (women are light-minded), wrongly attributing it to the Bible. His mistake serves as proof of his ignorance and thus of his own “femininity,” in the context of traditional Jewish patriarchal society in which women were not permitted to study sanctified texts. For in Hodel’s story lays a warning for the tailor himself – the cotton ball began chasing her aunt, until she eventually suffered a mental breakdown.

Whether it is the enchanted country inn or the working-people’s shtetl-tavern – both taverns embody the nihilist, chaotic terrain in Sholem Aleichem’s works, a thesis established by Miron. He sees in “The Enchanted Tailor” an important first step in the anti-progressive, pessimistic trend in his works. 20 20 Miron, “Afterword,” 237-248.

In the monologue “A mentsh fun Buenos-Ayres” (“A Man from Buenos-Aires”; 1909) Sholem Aleichem gives voice to his most immoral and ruthless character, worse than Baraban and Dodi: that of a top operate in an international sex slavery crime syndicate. Although this story takes place in a train, and is part of the collection “Rail-Road Stories,” the space here functions in effect as a tavern on wheels. The naïve narrator in the story tells at first how he and the man from Buenos-Aires warmed up to each other:

אױף פֿער ערשטער סטאַנציִע, װוּ מיר האָבן זיך אָפּגעשטעלט אױף עטלעכע מינוט, האָט ער מיך שױן געכאַפּט אונטער דער האַנט, צוגעפֿירט גלײַך צום בופֿעט, און גאָרנישט געפֿרעגט מיך, צי איך טרינק, צי נײן, האָט ער געהײסן אָנגישן צװײ געלזלעך קאָניאַק. באַלד נאָך דעם האָט ער געגעבן אַ װוּנק צו מיר, איך זאָל מיך אַ נעם טאָן צום גפּל, און אַז מיר זײַנען פֿאַרטיק געװאָרן מיט די אַלע מינים געזאַלצנס און פֿאַרבײַסנס, װאָס געפֿינען זיך אין יעדן בופֿעט, האָט ער געהײסן אָנגין צװײ קופֿל ביר, פֿאַררײַכערט - זיך אַ ציגאַר, מיר אַ ציגאַר - און אונדזער גוטפֿרײַנטשאַפֿט איז געשלאָסן געװאָרן.

At the first station at which we happened to stop for a few minutes, he grabbed me by the arm, led me straight to the buffet and, without asking me whether I drank or not, he ordered two glasses of brandy. Right after that he motioned to me to pick up a fork and when we were through with the various snacks and appetizers that you find at a railroad buffet, he ordered two mugs of beer, gave me a cigar, lit one for himself – and our friendship was as good as sealed. 21 21 Sholem Aleichem, “The Man from Buenos-Aires,” in Favorite Tales of Sholom Aleichem, trans. Julius and Frances Butwin (New York: Avenel, 1983), 516. The original can be found in Sholem Aleichem, Ale verk fun Sholem Aleykhem, Vol.10 (New York: Folks-Fond, 1927), 55-56.

Thus, with brandy, beers, and cigars, consumed in the railroad-station buffets along the way (the pair makes two more buffet-stops; the passengers even receive a booklet with the mapping of the station-buffets), the man from Buenos-Aires created the spatial atmosphere of a familiar taproom that puts his interlocutor at ease. This setup of generosity, of plying his listener with liquor and treats prepares the narrator to hear the man’s side of the story. It is one of several methods used by the wealthier man from abroad in his attempts to win over and legitimize his abusive and non-normative line of work in the eyes of the narrator.

In another famous monologue set in an urban modern space entitled “Yoysef” (“Joseph”; 1905), Sholem Aleichem again stages the modern conflict in a lively public eating place. In this instance, it is a small Jewish restaurant (“a idishe restoratsye”; perhaps parallel to a “Jewish tavern”), in a big Eastern-European city. The owner is a beautiful Jewish woman, a widow. Her daughter works alongside her as a waitress in the restaurant which functions as an underground meeting place for political radicals referred to as the “yenkelekh.” Here, a nameless, self-perceived bourgeois gentleman tells the story of his unrequited love to the attractive young waitress and of his fascination with the radical social atmosphere of the restaurant. The text doesn’t explicitly state that alcohol is served at the restaurant, but it also doesn’t state the contrary, and the restaurant serves food that one often consumes with wine or other forms of alcohol.

The story’s subheading “Story of a ‘Gentleman’ ” refers to the speaker’s nickname amongst the radicals; a name that underlines his strangeness amongst them. The speaker’s attraction to the radicals, and in particular to their charismatic leader Joseph, can be explained in homo-erotic terms, or by the possibility that the speaker is in fact a government agent, or a combination of the two. 22 22 See Dan Miron, Mipeh la’ozen: Sihot umah shavot ‘al omanut hamonolog shel Shalom ‘Alekhem (Ramat Gan, Israel: Afik, 2012), 179-220. The speaker gives the following description of the restaurant, including some hints at why he frequents it:

די מוטער... האַלט אַ ייִדישע רעסטאָראַציִע, כּשר. און איך, דאַרפֿט איר װיסן, כאָטש איך בין, װי איר זעט מיך, אַ יונגערמאַן, אַ הײַנטיִקער, און אַ שײנער פֿאַרדינער, און אַ קערבל אין בלאָטע, אי טאָמו פּאַדאָבנע, - פֿונדעסטװעגן עס איך דװקא כּשר. נישט מחמת איך בין אַזאַ צדיק און האָב חלילה מורא פֿאַר דעם װאָס קװיטשעט, נאָר, פּשוט, איך היט מיר אָפּ דעם מאָגן, - איז אײנס; און צװײטנס, זײַנען די ייִדישע עסנס טאַקע מער באַטעמט אױך... אַלזאָ האַלט זי אַ רעסטאָראַציִע, די אַלמנה הײסט עס, און קאָכט אַלײן און באַקט אַלײן; און זי, די טאָכטער הײסט עס, דערלאַנגט אַלײן צום טיש. נאָר װי אַזױ קאָכט מען דאָרטן! װי אַזױ דערלאַנגט מען דאָרטן! עס זינגט, זאָג איך אײַך, סע פֿינקלט און סע שעמערירט! דאָרט צו עסן איז אַ פֿאַרגעניגן. נישט אַזױ דאָס עסן אַלײן, װי דאָס אָנקוקן די מוטער מיט דער טאָכטער - אײנע שענער פֿאַר דער אַנדערער.

[The mother] [k]eeps a Jewish restaurant. Kosher. Oh, about that: well, I confess, for all I’m your progressive modern chap really, good income, scads of the old ready I don’t much mind parting with nor miss if I do, et cetera, I make it a point to eat kosher. Oh, it’s nothing to do with being observant. Good God, no! Don’t entertain the least scruple anent your grunting livestock myself. Sensible regard for the old turn is all it is, really. That’s one reason. Besides, you’ll agree Jewish dishes are far and away the tastiest. . . . Anyway, keeps a restaurant. The widow, that is. Does all the cooking on the premises herself, don’t you know. Daughter serves. Though what cooking, what service! I tell you it’s a song! It sparkles, it gleams! Sheer paradise, eating there. But the pleasure’s not in the eating so much as in feasting your eyes on the mother and daughter both. 23 23 Sholem Aleichem, “Joseph,” in Ken Frieden, Classic Yiddish Stories of S. Y. Abramovitsh, Sholem Aleichem, and I. L. Peretz (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2011), 109. The original can be found in Sholem Aleichem, Ale verk fun Sholem Aleykhem, Vol. 12 (New York: Folks-Fond, 1927), 72-3.

The speaker wants to create the impression that he is one of Heinrich Heine’s modern acculturated Jewish protagonists, whose one element they hold on to from their Jewishness is the cuisine of their heritage for its divine tastes, with a special fondness for cholent. But his fluent Yiddish, to name one example, suggests his Jewish identity is still stronger than he’d like to admit. This restaurant provides him with everything he needs as a single man in the big city: a hot meal, a connection to his roots, and a double, or possibly triple, sexual fantasy – he can feast his eyes on an attractive mother-and-daughter pair while feasting on tasty and familiar foods. The fact that the speaker, who brags about how well he does in business, chooses to frequent such a low-brow establishment says a lot about him and his motives. But more interesting for our purposes is the way Sholem Aleichem’s narrator speaks about an underground hot spot for Jewish socialists, spiked with dangerous and sexy elements, an attractive place where activists would meet and plan “konspireyshens” to overthrow the regime.

When the authorities get their hands on Joseph (whether because of the narrator’s snitching or otherwise), the radicals stay away from their favorite meeting place. Joseph’s arrest also affects the mother and daughter a great deal, because of the daughter’s infatuation with Joseph, and because of their political kinship. By the time Joseph is hanged, the underground restaurant had already closed down and vanished into thin air, and the mother, daughter, and the activists all fled the scene.

From the perspective of a bourgeois narrator, Sholem Aleichem provided an enduring portrayal of a popular revolutionary meeting place. It also contrasts starkly with the bourgeois gentlemen’s club where the narrator sometimes visits to have a drink and play cards. This portrayal is also unique compared to those found in Peretz’s work. Peretz was close to radical political circles in real life, but in his writing, he tended towards a moralistic condemnation of a tavern, as previously noted.