Nov 01, 2022

Jewish cultural figures who would become members of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee signing an appeal to world Jewry to support the Soviet war effort against Nazi Germany, Moscow, 1941. (Front row, left to right) Dovid Bergelson, Solomon Mikhoels, and Ilya Ehrenburg; (second row) David Oistrakh, Yitskhok Nusinov, Yakov Zak, Boris Iofan, Benjamin Zuskin, Aleksandr Tyshler, Shmuel Halkin. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum via YIVO Encyclopedia)

ABSTRACT

Soviet nationalities policy towards its Jewish citizens was in flux during the first two decades of the new communist state’s existence. While Yiddish was made an official language and benefitted from unprecedented state support in the 1920s, the 1930s were largely marked by renewed repressions. The outbreak of the Great Patriotic War between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in June 1941 meant a new renegotiation of power between Yiddish culture and the Soviet government. Previously stifled Jewish connections across borders were renewed, as is best represented by a major August 1941 rally in Gorky Park, which was broadcast to a Jewish audience abroad and from where Dovid Bergelson made an appeal to his “brother Jews of the entire world!” This article looks at the wartime artistic and journalistic output of Dovid Bergelson and Dovid Hofshteyn, two prominent Soviet-Yiddish writers and members of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, to see how these writers appropriated Soviet terminology which called the Russians the “elder brothers” of the Soviet family in order to paint Soviet Jews as the elder brothers in a worldwide Jewish family of their own. To do so, they reminded their audience of the Jewish connection to Ukraine, which was currently under attack, demonstrated the ways that Soviet Jews maintained an authentic connection to that land, and exhibited the effect that Soviet power had had in cultivating the Soviet Jews for their new role, having turned them into suitable leaders of the future Jewish family.

Click here to read a pdf version of this article.

On August 24, 1941 some of the most famous figures of the Soviet Jewish intelligentsia gathered for a wartime rally in Moscow’s Gorky Park. The speakers that day included Solomon Mikhoels, director of the Moscow State Jewish Theater; Ilya Ehrenburg, one of the best-known novelists and journalists in the country; Peretz Markish, the Yiddish poet; and Dovid Bergelson, who was at that time perhaps the most famous Yiddish writer in the Soviet Union. Bergelson began his speech by addressing his “Dear brothers and sisters, Jews of the entire world!” 1 1 Dovid Bergelson, “Lo amut ki ekhye! Ikh vel nit shtarbn, ikh vel lebn!” in Brider yidn fun der gantser velt! (Moscow: Melukhe-farlag “Der emes”, 1941), 17-20. Published in English translation “From Speeches Delivered at the First Jewish Rally (August 24, 1941). Document 9,” in Shimon Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism: A Documented History of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR (Routledge: London & New York, 2013), 180-181. In some ways, he meant this literally: the rally was broadcast over the radio to an audience both within the Soviet Union and abroad. He used the speech to describe the horrors currently being carried out by the Nazis and to link them to the thousands of years of injustices suffered by the Jews, and then ended with a rallying cry of three short, powerful statements, which he spoke in the collective voice of the Jewish people: “Lo amut ki ekhye. Ikh vel nit shtarbn. Ikh vel lebn!” (“I will not perish. I want to live. I will live!”). Aimed at a worldwide Jewish audience, Bergelson gave these lines in a mix of Hebrew and Yiddish, the first one even coming directly from Psalm 118 of the Hebrew Bible. This reference helped strengthen his theme of continuity of the Jewish people, both out of the past and into the future. The orientation to such an international Jewish public, along with the very rally itself, was surprising in the USSR: Soviet education and propaganda before the war had taught that there was no significant common destiny between the Soviet Jew building socialism and the Western Jew in capitalist countries, and did much to prevent the establishment of such nationalist ties.

The 1920s had initially seen an unprecedented level of state support for minority languages and cultures in the Soviet Union; Yiddish in particular benefitted, as it was identified as the language of the Jewish working class and promoted over Hebrew, which was viewed with suspicion in the world’s first socialist state thanks to its Zionist and religious connections. The 1930s, however, had been largely marked by the repression of national expression to such an extent that even Der emes, the central Soviet Yiddish newspaper, was shut down by the authorities in 1938. The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 precipitated massive changes in every aspect of Soviet life, including an immediate and far-reaching one in internal Soviet nationalities policy, particularly for the Jews: the shocking outbreak of war prompted a reversal on the crackdown and brought a return to the practices which had initially encouraged Yiddish expression.

On August 16, 1941 many of the the leading Yiddish writers of Moscow, including Dovid Bergelson, Peretz Markish, and Leyb Kvikto, sent a proposal to the Soviet Information Bureau (Sovinformburo), reading: “We, members of the Jewish intelligentsia, consider it appropriate to organize a Jewish rally aimed at the Jews of the USA and Great Britain, and also at Jews in other countries. The purpose of this rally would be to mobilize world Jewish public opinion in the struggle against fascism and for its active support of the Soviet Union in its Great Patriotic War of liberation.” 2 2 “A Proposal to Organize a Jewish Rally in Moscow. Document 7,” in Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism, 173-174. As radical as it was, considering the circumstances outlined above, the situation during the first two months of war had grown so dire that this proposal was accepted, and on August 24, 1941, the First Jewish Rally was held in Moscow’s Gorky Park.

When the Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Vyacheslav Molotov famously addressed the nation by radio on the first day of the Nazi invasion, he also ended his speech with three brief and powerful sentences, just like Bergelson: “Our cause is right. The enemy will be defeated. Victory will be ours!” 3 3 “Molotov addresses the Soviet people re. German invasion.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM). Accession Number: 1995.147.1. RG Number: RG-60.0880. Film ID: 25. Yet despite the similarity in form, the two functioned completely differently. Unlike Molotov’s radio address, which urged unity among “the entire population of our country, all workers, peasants, intellectuals, men and women,” Bergelson’s speech was aimed toward a specifically Jewish audience. Whereas Molotov’s speech used the first-person plural (“Our cause is right”) to convey a sense of Soviet collectivity, Bergelson chose the first-person singular (“I will live”) to express a distinctively Jewish cause. Such utterances mark just how greatly power had been renegotiated between Soviet authorities and Yiddish culture upon the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. When Soviet power was at its weakest, it needed to surrender some of the absolute control of literature and culture that had been won through repressions of the 1930s, particularly in the field of Yiddish literature. As a part of this renegotiation of power, the Yiddish language was turned into a weapon, and tremendous strength was gained by those who knew how to use it well – namely, the leading figures of Yiddish literature and culture.

That power is best exemplified in political terms by the Sovinforburo’s creation of the Jewish Antifascist Committee (JAC) in the aftermath of the First Jewish Rally. Many of the Committee’s leading members were figures of literature and culture; Solomon Mikhoels was named Chairman of the JAC in December 1941. Five such Anti-Fascist Committees were established in early 1942: one each for Slavs, women, youth, scientists, and Jews, intended to appeal to their respective target demographic for political, monetary, and military support for the Soviet war effort. 4 4 The founding and history of the JAC is well summarized in “Introduction: Night of the Murdered Poets,” by Joshua Rubenstein, in Stalin’s Secret Pogrom: The Postwar Inquisition of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, eds. Joshua Rubenstein and Vladimir P. Naumov (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 1-64. As part of that work, the JAC established Eynikayt (Unity), a new Yiddish newspaper first published on June 7, 1942, appearing every ten days and later as a weekly, which was aimed at a readership both in the Soviet Union and abroad. 5 5 The history of Eynikayt is described in Dov-Ber Kerler, “The Soviet Yiddish Press: Eynikayt During the War: 1942-1945” in Why Didn’t the Press Shout?: American and International Journalism During the Holocaust (Yeshiva University Press, 2003), 221-249. However, the circulation of Eynikayt was so limited that its influence must be questioned; approximately 7,000 copies of the newspaper circulated in the USSR and only 3,000 abroad. 6 6 These are the numbers given by Gennady Estraikh and based on “Bulletin on the activities of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee in the USSR (August 1941 - August 1945)” GARF. F. R-8114. Op. 1. D. 1063. L. 32; Appendix Document No. 4.1), as described in “Smertel’no opasnoe natsional’noe edinenie,” in Sovetsakaia geniza: novye arkhivnye razyskaniia po istorii evreev v SSSR. Tom 1, eds. Gennadii Estraikh and Aleksandr Frenkel’ (Academic Studies Press / BiblioRossica: Boston / Saint Petersburg, 2020), 296-297. The power of such a newspaper can therefore be said to be more symbolic than literal: it meant something for the Soviet Union to possess an outlet for publishing these well-established writers who, for better or worse, had connections and name recognition in the West, even if they did not have the readership of a more popular Soviet writer like Fayvl Sito. Nevertheless, it was largely within the pages of Eynikayt that the Yiddish writers were tasked with creating a new type of Soviet Yiddish culture, one international in reach. To this end they instrumentalized the Yiddish language itself, turning it into a weapon that would galvanize the Soviet war effort. The poet Dovid Hofshteyn summed up the newfound might of the Yiddish language in one of his wartime poems, in which he describes a factory working day and night to produce arms for the front; the poet explains that he is equipping himself for battle as well, but that “my weapons are words.” 7 7 In Yiddish, “mayn gever iz verter.” The poem was written in Ufa in June 1942, and published in Dovid Hofshteyn, Ikh gleyb (Moscow: Der emes, 1944), 42.

To speak to their new international audience, no matter how small it may have actually been in number, the Yiddish writers also appealed to worldwide Jewry’s common cultural memory and shared geographic homeland in the lands of the former Pale of Settlement, particularly Ukraine – the territories of the Soviet Union presently occupied by Nazi Germany. Millions of Jews in the West had either come from this land themselves or could trace their family roots back to there over the last few generations and thus maintained a vested interest in these communities. American Yiddish newspapers like Forverts published updates from Jewish communities in Ukraine and elsewhere in the USSR and American landsmanshaftn kept the sense of community connection alive for millions of emigrants. Similarly, many of the Soviet Jews who had migrated to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic had also come from what had been the Pale over the previous 25 years. Though Moscow was certainly the center of all cultural life in the USSR, it was a relatively new center for Yiddish: its leading figures of intellectual and cultural life were not Moscow born-and-bred, and thus the entire center carried a strong connection to the periphery – particularly Ukraine, which was itself a complicated site for Soviet power. It was not entirely Soviet before 1939, as large amounts of what would become the western territory of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and millions of ethnic Ukrainians were located in the Second Polish Republic; nationalist sentiment was also strong in Ukraine, reflected in the independent state it managed to maintain during the Civil War from 1917-1920. It therefore benefited the Soviet government as well to show how Ukraine was a fundamental part of this Soviet family, emphasizing the tripartite mixing of Jews, Ukrainians, and Russians.

The dynamic between the Yiddish writers and Soviet power remained fluid over the course of the war and its immediate aftermath. In 1943, as the tides of war began to change and the Soviet Red Army liberated territory on its drive westward, the task of the Yiddish writers changed again: they had to find a way to make sense of the destruction they were confronted with, to help rebuild a broken world, and to remember it. Yiddish writers pushed the limits of acceptability in their complex expression of documentation and mourning. By focusing on two individuals, Dovid Bergelson and Dovid Hofshteyn, and reading their creative work and journalism of the war years, I illustrate the changes in their thinking, in their task, and in the relationship between Soviet power and Yiddish literature. Arkadii Zeltser has demonstrated that Eynikayt was dominated by articles glorifying Jewish heroism during the war, which far outnumbered those about the Nazi atrocities. He reads the permissibility of such pieces as driven by the urge to dispel antisemitic tropes about the Jewish incapability to engage in combat, by an overall anxiety around the increased Russo-centrism in the military, the party, and society as whole, and by dissatisfaction with the Jews being depicted as “little brothers” to the Russians in the Soviet family.

8

8

See Arkadii Zeltser, “How the Jewish Intelligentsia Created the Jewishness of the Jewish Hero: The Soviet Yiddish Press” in Soviet Jews in World War II: Fighting, Witnessing, Remembering, eds. Harriet Murav and Gennady Estraikh (Academic Studies Press, 2019), 104-129.

Despite initially being discouraged as “Great Power chauvinism,” Russian nationalism had been gradually rehabilitated in the USSR starting in 1933. In 1935, Stalin declared that “the mistrust of Russians had been defeated” and on February 1, 1936 Pravda ran an editorial proclaiming the Russian nation “first among equals,” which soon became a standard epithet. The “brotherly help” the Russian people had provided non-Russians became an immense theme of nationalist propaganda in the years that followed.

9

9

See Terry Martin, The Affirmative Action Empire: Nations and Nationalism in the Soviet Union, 1923-1939 (Cornell University Press, 2001), particularly the section “The Friendship of the Peoples,” 432-461. Though Martin’s book ends in 1939, it shows how the language describing the relationship between nationalities in the USSR had been established on the eve of war.

The promotion of Russian nationalism was accelerated during the Great Patriotic War, the title of which itself was a callback to Russian Imperial history, and Russians were singled out as the “elder brothers” of the USSR.

10

10

See David Brandenberger, “‘…It Is Imperative to Advance Russian Nationalism as the First Priority’: Debates within the Stalinist Ideological Establishment, 1941-1945,” in A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin, eds. Ronald Grigor Suny and Terry Martin (Oxford University Press, 2001), 275-300.

Unlike some Soviet Yiddish writers, Bergelson and Hofshteyn did not fight back against the patronizing position of the Jew as “little brother.” Instead, they reappropriated that language to paint the Soviet Jews as the elder brother in their own worldwide Jewish family.

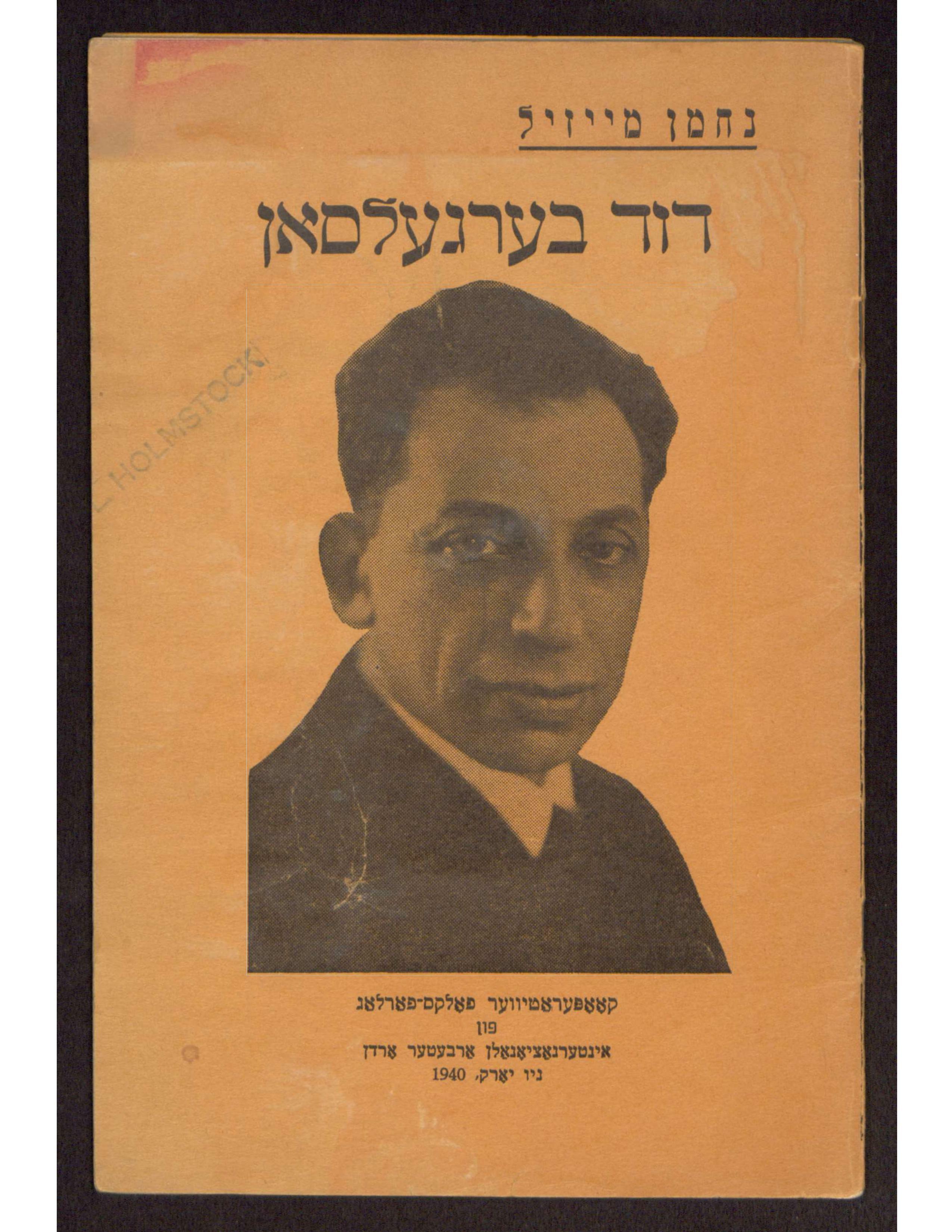

David Bergelson, from a literary biography of Bergelson by Nachman Meisel, 1940, published by the kooaperativer folks farlag of the Interational Workers Order. Digitized by Cornell University Library.

These two writers are fitting examples, both for what they shared and for what distinguished them. Bergelson had spent more than a decade in emigration living in Berlin. Only in 1934 did Hitler’s rise to power, combined with other pressures of being a Yiddish writer without a local audience, finally compel him to return to the Soviet Union. Bergelson’s early modernism had shown the death and decline of traditional life in the shtetl and small towns of Ukraine, but after his repatriation he turned his gaze to rebirth instead and was particularly concerned with the construction of a new Jewish homeland in the Jewish Autonomous Region in the Far East. Hofshteyn’s attitude toward place was quite different. He lived abroad in Palestine for only two years between 1924-1926 before returning to the Soviet Union, and instead of the cosmopolitan capital Moscow he chose to live in Kyiv, the spiritual origin of the Kyiv Group of modernist Yiddish writers. The fact that he was the only major writer from the Kyiv Group to remain in that city represents his continued attachment to the Ukrainian land. Amelia Glaser has shown how, in the 1930s, Hofshteyn used his translations of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko to describe Ukraine in a way that allowed him to reflect on the Jewish relationship to Ukraine and Ukrainians, as well as on the nation within the socialist state.

11

11

See the chapter “My songs, My Dumas: Rewriting Ukraine” in Amelia Glaser, Songs in Dark Times: Yiddish Poetry of Struggle from Scottsboro to Palestine (Harvard University Press, 2020), 174-210. Shevchenko had been canonized by the Soviet state as the best example of Ukrainian literature in what Katerina Clark in Moscow, The Fourth Rome (Harvard University Press, 2011), calls the “Great Appropriation” in which writers of the past, and of non-Russian languages, were repackaged in order to reflect current Marxist values. Glaser shows how Hofshteyn’s translations of Shevchenko are therefore an example of the poet using the tools of the state in unexpected ways as he showed the links between minority nationalities in the USSR.

During the war, while both were members of the JAC and contributors to Eynikayt, many of those differences between them were diminished as both writers found that their displacement and distance from the action of the war heightened their sense of origin and connection to the lands of Ukraine and its literary and cultural heritage. Regarding that geographic homeland as common between Soviet Jews and their “brother Jews” around the world, they used that shared attachment as a tool to create a strong, worldwide but uniquely Soviet-Yiddish culture.

Already at the beginning of the war, both Bergelson and Hofshteyn sought to remind their Soviet and international audience of the Jewish connection to the land and culture that was under attack. It was not coincidence that the two, like so many of the Yiddish cultural leaders of the time, came from Ukraine specifically, which in some ways came to be recognized as the origin point of Soviet-Yiddish culture. The reasons for this are multiple: on the practical level, large amounts of the former Russian Empire’s Jews lived in the independent Baltic states or the Second Polish Republic between the revolutions and 1939, and many of the Belarusian Yiddish literary elite had been purged in the 1930s, leaving only the Ukrainian Jewish writers. Yet it was also driven by literature: the same way that Shevchenko had been canonized by the state, the Ukrainian Yiddish writers Mendele Moykher Sforim and especially Sholem Aleichem were idolized by the regime as the official classics of Yiddish literature, and continuity was sought.

Bergelson and Hofshteyn demonstrated the particular ways that Soviet Jews maintained an authentic connection to that land, the origin of both Western and Soviet Jewish life, and therefore established a sense of continuity that marked themselves as the “elder brother” in an international Jewish family, in the same way that Russians were in the Soviet one. To this end, the writers wanted to exhibit for worldwide Jewry the effect that Soviet power had had in cultivating the Soviet Jews for this role, having turned them into suitable leaders for the Jewish future. Bergelson and Hofshteyn put forth these arguments despite their distance from the actual events of the war; both writers in fact capitalized on that distance, utilizing their physical and emotional safety in ways that allowed them to process and report on the horrors of the War and Holocaust, which were not possible for those closer to the action, for whom the impossibility of representing the horrors was a more common motif. They wrote through the 1941 invasion and their own evacuations, and continued their witnessing from a distance after the course of the war changed in 1943 and they were permitted to return to Moscow. Their viewpoints evolved once again in 1944 when the physical distance from the evidence of the Holocaust and other Nazi atrocities was finally diminished. At that time, both writers balanced the question of Jewish leadership with some of the very first and most personal calls for remembrance and confrontation with the horrors they saw upon their return to Ukraine.

1941-1942: Evacuation in Ufa, Tashkent, and Kuibyshev

The success of the First Jewish Rally in August 1941, which led to the creation of the JAC and the eventual publication of Eynikayt in June 1942, almost resulted in an even earlier revival of Der emes, to which the Central Committee gave its approval to begin publishing in Moscow on October 15, 1941. 12 12 “Proposal to the Central Committee to Publish a Yiddish Newspaper in Moscow. Document 15,” in Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism, 189. That plan was unfortunately halted when the advancement of the German army necessitated the hasty evacuation of Moscow in mid-October. Many of the Moscow Yiddish writers, including Bergelson, were sent to Tashkent, capital of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in Central Asia. The 21,472 Jews who lived in Tashkent in 1939 were soon joined by thousands of refugees from the western Soviet republics as well as Poland, of whom it is estimated that up to 63% were Jewish. 13 13 The first wave of evacuees came to Tashkent in the late summer and fall of 1941, followed by a second wave in the summer of 1942. In August 1942 alone fifty-five thousand evacuees were reported to have come through Tashkent station. See Rebecca Manley, To the Tashkent Station: Evacuation and Survival in the Soviet Union at War (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009). A sizable Yiddish-speaking community thus emerged, buoyed by such institutions as the Moscow State Jewish Theater (GOSET) which had also been evacuated there. 14 14 For a history of the Yiddish theater in Tashkent, including the years of GOSET in evacuation, see Maks Veksel’man, Evreiskie teatry (na idish) v Uzbekistane: 1933-1947, (Filobiblon: Jerusalem, 2005). Bergelson shared the long train ride from Moscow to Tashkent with other notable names of the Moscow intelligentsia, including the famous Soviet literary theorist Viktor Shklovsky, and the Yiddish poet Peretz Markish. 15 15 Markish gives a fictionalized description of the train ride in his novel Trot fun doyres (March of the Generations), and it is recounted by his wife Esther Markish in her memoir, The Long Return (New York: Ballantine Books, 1978), 114-119. In fact, Tashkent was such a center for the Yiddish literary elite that Bergelson found himself as next door neighbor to Markish and his wife, with the writer Der Nister on the floor directly above them.

Hofshteyn had been similarly evacuated as the Nazis approached Kyiv; he was sent to Ufa, Bashkiria – a large industrial city to the west of the Ural Mountains – along with 104,000 other refugees of which Jews were a significant percentage. 16 16 The conditions of Jewish evacuees in Bashkiria during the war are described in Emma Shkurko, “Evakuirovannye evrei v Bashkirskoi ASSR (1941-45 gg.): demograficheskie, kul’turnye i psikhologicheskie aspekty,” in Evreiskie bezhenitsy i evakuirovannye v SSSR, 1939-1946, ed. Zeev Levin (Assotsiatsiia Khazit ka-kavod: Jerusalem, 2020), 104-124. While there, he and his wife were billeted at the home of Bashkir writer Akhtiam Ikhsan, and Hofshteyn took odd jobs doing handywork and spent his nights pouring over reports from the front and writing. 17 17 The Hofshteyns’ life in evacuation is described by his wife Feyge Hofshteyn in her memoir, Mit libe un veytik (Reshafim: Tel Aviv, 1985), 27-34. There, so far from home, the writing was meant to convey connection to the land of the former Pale which had been evacuated, as well as how Soviet power had both improved that territory and the place of the Jews in society as a whole. In such an understanding, Jews had become full members in a multinational family, which included all the peoples of the USSR – to the point where one could feel at home even with Uzbeks or Bashkirs. At the same time, the texts’ orientation to a presumed Jewish reader of Yiddish cements the Soviet Jews’ position in that family as well.

One of those pieces of Hofshteyn’s writing, which describes the time spent in Ufa between 1941 and 1943, is a short story found in the archive of the JAC, called “The Monologue of Tevye Not-the-Dairyman.” 18 18 D. Gofshtein, “Monolog Tev’e ne molochnika,” Gosudarstvennyi arkhiv rossiiskoi federatsii (GARF), f. 8114, op. 1, d. 128, 238-239. The story begins in the voice of its eponymous character, who is a local produce seller the author meets at a market in Ufa: “I see that you’re also from Ukraine,” the produce seller says, immediately establishing a connection between them, an identity to which their shared geographic homeland is fundamental. He goes on: “You’ve probably read Sholem Aleichem. Who among the Jews has not read Sholem Aleichem? I can tell you that I’m also named Tevye, though not Tevye the Dairyman…” he continues, establishing the second important pretext for worldwide Jewish culture and solidarity: their literary culture as exemplified by Sholem Aleichem, the father of Yiddish literature.

The Ukrainian Jew elaborates on his connection with his namesake, one of Sholem Aleichem’s best-known characters, the father of seven daughters who each take very different paths. Alluding to Tevye’s daughter Hodl, who follows her revolutionary husband into exile in Siberia, he says, “I’m also the father of a daughter, but with her it’s the opposite… Tevye’s daughter went from Ukraine to Siberia, and she went because she was driven there. And my daughter, at her own will, is going from western Siberia to the Ukrainian front.” 19 19 Hofshteyn’s description of the Soviet Jew as Hodl predates and predicts the analysis of Yuri Slezkine in The Jewish Century (Princeton University Press, 2004). In his recounting of Russian Jewish history, Slezkine describes the early embrace of revolution by Russian Jews, whom he calls “Hodl’s children,” and who left the Pale of Settlement for the Soviet interior. Having received six months of training as a machine gunner, this version of Tevye’s daughter is not persecuted by the Tsar but instead empowered by the Soviet state, and is now equipped with the tools needed to return to the traditional Jewish homelands in Ukraine and help liberate them. In this story Hofshteyn succinctly shows his perception of how Soviet Jews remained connected to their land and culture while also modernized by Soviet power. Such a connection was vitally important during the first years of war, and was something that Hofshteyn and Bergelson used to emotionally connect their worldwide Jewish audience as they made both the case that worldwide Jewry was obligated to help the war effort in any way that it could and that the Soviet Jews were well-suited to lead that fight.

While in Ufa, Hofshteyn also continued to work on several poems which would go on to be included in the collection Ikh gloyb (I Believe), the publication of which again represents the desire for a far-reaching audience. It was published by Der emes in the Soviet Union in 1944, and in the United States by the Yiddisher Kultur Farband (YKUF) just one year later, thanks to the help of a group of landsmen from his home shtetl of Korostyshev who had settled in New York City. Their help was fitting, since Hofshteyn described the collection as having grown out of the atmosphere of Korostyshev.

20

20

As described by Hofshteyn in his letter to Kalman Marmar, 18.5.1946, in Briv fun sovetisher shraybers, ed. Mordechai Altshuler (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1979), 148.

The book, which celebrates a Jewish home in the diaspora, actually begins with the title poem in which Hofshteyn’s poetic voice regrets the diasporic condition of the Jews:

eyn oysbrukh nokh dem tsveytn geyt,

un vider vert

tsezeyt, tseshpreyt,

tseshtoybt,

vos shoyn ineynem iz geven —

un dokh mayn folk nokh gloybt,

az oyb

bashert

iz bayzayn umetum, —

tsi heyst es den

inergets nit?!

One generation sinks into the abyss

one eruption after another goes on,

and again, it

scatters, spreads,

disperses

that which had once been together —

and yet my people still believe

that if

destiny

disperses

is now everywhere, —

does it not mean

it is nowhere?

21

21

Dovid Hofshteyn, “Ikh gloyb” in Ikh gloyb (New York: IKUF, 1945), 9.

For Hofshteyn, however, the problem is eluded because he is what he calls a “Jew of the new style,” one who is not defined by the same liminal everywhere/nowhere status like the generations which have come before and sunk into the abyss. Instead, he does have a specific homeland and he belongs to those of “the great here, / my great home - / the USSR!” In plain and clear language, Hofshteyn’s poetic voice expresses the fact that Soviet power has not only given the Jews purpose and strength, but it has empowered them in their own homeland, the space in which they feel literally and spiritually grounded. In this sense, the Soviet Union has rectified the inherent tension of life in the diaspora, and Hofshteyn’s poetry predates what Harriet Murav describes as the way “Postwar Soviet Jewish literature radically reworks the traditional Jewish opposition of ‘diaspora versus Israel,’ adding new dimensions to what constitutes the Jewish notion of home.”

22

22

Harriet Murav, Music from a Speeding Train: Jewish Literature in Post-Revolution Russia (Stanford University Press, 2011), 248-249.

That a nation should be tied to territory was fundamental to Stalinist nationalities policy, yet Hofshteyn makes clear to the reader that the territory he sees as a basis of the Jewish nation is not the result of Jewish resettlement (either within the Soviet Union or in Palestine), but a reclamation of the very land on which they have already lived, and to which “the nostalgia is heavy.”

23

23

Dovid Hofshteyn, “Tfiles” in Ikh gleyb (Moscow: Der emes, 1944), 25. According to his wife Feyge Hofshteyn, this poem was written in Ufa in the summer of 1942. Mit libe un veytik, 31.

Bergelson was similarly removed from the lands under attack while in evacuation in Tashkent, but kept his attention focused on the action and kept writing about it. His very first essay about the Nazi invasion appeared in 1941 and, like Hofshteyn’s poetry, was published simultaneously in the Soviet Union by Der emes and in the United States by the Organisation for Jewish Colonization in Russia (YKOR). As David Shneer proved in his reading of the text, “Jews and the War with Hitler” demonstrates for an American Jewish socialist readership how the Soviet Union built and gave a homeland to a new type of Jew. 24 24 See David Shneer, “From Mourning to Vengeance: Bergelson’s Holocaust Journalism (1941-1945)” in David Bergelson: From Modernism to Socialist Realism, eds. Joseph Sherman and Gennady Estraikh (London: Legenda, 2007), 248-267. By 1942, as the situation grew more desperate, so did Bergelson’s pleas to a Western Jewish audience. Though he himself remained in the Soviet Union, his words were able to reach them; one such example comes from the text of a speech sent to be presented at the Conference of British Jews on September 5, 1942 - an example of Bergelson actually having a concrete audience. 25 25 D. Bergelson, “Privetstvennoe pis’mo izvestnogo evreiskogo pisatelia D. Bergel’sona ot imeni sovetskikh evreiskikh pisatelei Konferentsii britanskikh evreev.” GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 113, 349. His speech greets the conference “in the name of Soviet Jewish writers” and describes the trials facing the Jewish people in Eastern Europe. In words very similar to Hofshteyn’s poem, Bergelson’s speech explains how diaspora, “being scattered all over the world,” has actually harmed the Jews and led them to this trouble. Rather than a Zionist negation of the diaspora, this is in line with Soviet thinking that ties nation to territory. Yet when he specifically describes the Soviet Jews as “the eldest brother,” he subverts Soviet talking points by reaching beyond the “brotherhood of nations” within the Soviet Union – among which Russians were always “first among equals” – and places Soviet Jews in another, entirely Jewish family spanning the globe. By designating the role of eldest brother to the Soviet Jews, he implicitly assigns them the role and responsibilities of a leader within that family.

While in Tashkent in late 1941, Bergelson began writing his first wartime play, Kh’vell lebn! (I Will Live!) - the title of which reappropriated his own words from his speech at the Gorky Park rally earlier that summer.

26

26

The timeline is established by Joseph Sherman in “David Bergelson (1884-1952): A Biography,” in David Bergelson: From Modernism to Socialist Realism, 60. Based on an unproduced screenplay for a film version of I Will Live! dated 1942 and intended for the Kyiv Film Studio which was found in the JAC archive, Olga Gershenson shows that the play was likely revised after the plans for filming fell through. See Olga Gershenson, “The First Phantom: I Will Live! (1942)” in The Phantom Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and Jewish Catastrophe (Rutgers University Press, 2013), 29-39.

He was far from the only one writing plays in Yiddish at this time and though I Will Live! was never actually performed in the Soviet Union, others were.

27

27

Bergelson’s play was, however, performed by the Nayer Yidisher Folks Teater in New York, with a premier of December 19, 1944 as advertised in Forverts (November 29, 1944, p. 7), as well as by Habimah in Tel Aviv - though it received an unfavorable reception. See Ben-Ami Feingold and Ruth Bar-Ilan, “The Hebrew Theater: Between the War and the Holocaust,” Israel Studies (Fall 2003, vol. 8, no. 3: Israel and the Holocaust), 168-193.

The move to the theater was grounded in the idea that it could reach an audience, as Yiddish theaters in evacuation attracted an even greater number of spectators than they had before the war, including Jews who didn’t know Yiddish but in whom news of the destruction of the Jews aroused feelings of national consciousness; the theater became a place where those feeling resonated and thus acquired increased importance as sites of national expression.

28

28

See “Teatr. Istoriia evreiskogo teatra. V sovetskom soiuze do razgroma evreiskoi kul’tury (1918-1949)” in Elektronnnaia evreiskaia entsiklopediia.https://eleven.co.il/jewish-ar...

Bergelson’s play touches on many of the same themes of Jewish strength and survival as the Rally speech with which it shares its name. It is set in a small town in Ukraine as the invading German army approaches, and its characters are Russians, Ukrainians, and Jews who exemplify the Soviet notion of Friendship of the Peoples. When the Germans enter the village, several main characters flee to the woods to become partisans, while others are taken prisoner. The main drama of the play surrounds the Germans’ search for a notebook with data about the local agricultural-technical station, and it ends with the Red Army and partisans liberating the village after Frida, a young Jewish woman, cunningly leads the German soldiers into a trap. The plot has similarities to Markish’s An Eye for an Eye and to other pieces from the Yiddish theatre at that time, such as Vengeance by Israel Levin: the wartime Yiddish plays all emphasise Jews working together with Russians and Ukrainians, feature a brave and talented female heroine, and end with partisans and the Red Army achieving their goals. 29 29 Israel Levin was an actor in the Belarusian GOSET, and his play Vengeance (Nekome) was staged by the theatre in evacuation in Novosibirsk in 1942. See Leonid Smilovitsky, Jewish Life in Belarus: The Final Decade of the Stalin Regime, 1944-1953 (Central European University Press, 2014),189. There was no directive on how to write wartime theater, yet the Yiddish writers — perhaps from years of training under Socialist Realism — were still able to grasp what forms and plots were acceptable, thanks to examples from the rhetoric all around them in different genres.

The seemingly straightforward nationality question in Bergelson’s play is challenged via characters who are marked by histories of migration and therefore do not so neatly align, such as the German Jew Professor Kronblit, who fled from the Nazis and found safety in the Soviet Union. Despite the calls for worldwide Jewish solidarity, Bergelson uses Professor Kronblit as a punching bag for his frustrations with Western Jews, which were growing at the time. In two separate articles sent to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency in New York in 1943, for example, he both praised Jews worldwide for their help in the fight against Nazi Germany, and simultaneously complained that they were not contributing enough capital to the Red Army — neither financial, in terms of money, nor human, in terms of their sons. 30 30 D. Bergelson, “What Will Your Reply Be?” GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 37, 160. D. Bergelson, “How Jews of Different Countries Help the Red Army” GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 346, 40-47. Unlike the Soviet Jews who are quick to rise up and join the Russians and Ukrainians in partisan resistance in the play, Kronblit exemplifies the reticence of Western Jews when his first impulse upon the Nazi invasion is to commit suicide, “like so many German Jews.” 31 31 David Bergelson, ““Kh’vel Lebn! Lo Amut Ki Ekhye. (Drame in 3 Aktn).” Sovetish heymland 11 (1968), 34. I cite the version published by Sovetish heymland long after Bergelson’s rehabilitation. Its contents are similar to the many unfinished versions available in the JAC archive.

Bergelson also made reference to a supposed mass suicide of Jews in Berlin and Vienna during his Gorky Park speech, which gives the impression that he did indeed believe this was happening and was truly concerned about a suicide epidemic among German Jews. Suicide carries a well-established symbolic meaning in Bergelson’s creative work. His early novel The End of Everything (1913) ends ambiguously with the possible suicide of the protagonist Mirl; it is the driving force of his 1920 novel Descent, which takes place in the aftermath of death by suicide, and is also present in “The Deaf Man” (1910) and “Among the Refugees” (1927). Overall, suicide in Bergelson’s earlier work represents one of the only options of escape available to the individual trapped in the shtetl environment. In “Among the Refugees,” even though set in Berlin, the young would-be-terrorist who takes his own life in the end implies it is because he remains metaphorically in the shtetl. Professor Kronblit, however, does not have to resort to this. He is talked out of it by the local Jew Avrom-Ber, whose gives a moving monologue ending with the words “Lo amut ki ekhye!”: “I will not die, I will live!” 32 32 Ibid., 35.

As an educated Jew fleeing from Hitler’s Germany to the Soviet Union, it is possible to read Professor Kronblit as a representation of Bergelson himself – however Avrom-Ber’s repetition of Bergelson’s own lines turns him into another suitable stand-in for the author. His monologue can therefore be read as а recreation of Bergelson’s speech at the Gorky Park rally, which allows Kronblit to serve as a personification of the entire worldwide Jewish audience which Bergelson had addressed with it. Bergelson had hoped to rally Western Jews out of both despair and complacency with his words, which is just what Avrom-Ber does to Kronblit. Kronblit ultimately does not need to commit suicide because here in the Soviet Union he is being offered protection: a community of strong Jews, living shoulder to shoulder with their Russian and Ukrainian comrades. Bergelson shows how the Soviet state has turned the Soviet Jew into a leader in the international population of Jews; it has rescued the Jew from the oppressive shtetl environment from which he once had to die in order to escape, and transformed that territory into something worth fighting for.

The play’s themes of worldwide Jewish connection to the land under attack and the transformation of Soviet Jews into a leading “elder brother” are also to be found in Bergelson’s wartime journalism. One such article, “The Young Soviet Jew,” demonstrates this by drawing a metaphorical connection between an old, pious Jew named Moyshe Leyb Shoykhet, who supposedly lived in the author’s home shtetl, and the young Lieutenant Shoykhet, who heroically gunned down eighty-five Nazis at Stalingrad.

33

33

David Bergelson, “Der yunger sovetisher yid”, Eynikayt 7 November 1942, 2.

The name Shoykhet comes from the word for a ritual slaughterer in Judaism, the echo of which lives on in the young Lieutenant who is able to kill Nazis. Though not actually related, their shared last name helps to continue the metaphor of family relations and represents just how much of “an inheritance from the pious Jew”

34

34

Ibid., 2.

lives on in the young Soviet Jew. The relationship shows that the changes to Jewish life brought by rapid Sovietization have not nullified traditional Jewish life but transformed and strengthened it. Reading Bergelson’s creative work and journalism from the early years of the war shows the unity of the Soviet patriot and the proud Jew within him, whereby the two identities simply reinforce one another: they were two parts of the same family.

35

35

In her chapter on Bergelson’s wartime and postwar activities, Harriet Murav explores the ways that Bergelson’s Jewish identity, his role as “a patriot to the Jewish people,” truly rose to the surface at this time. See “The Gift of Time,” in David Bergelson’s Strange New World: Untimeliness and Futurity (Indiana University Press, 2019), 322-360 (digital version).

Bergelson left Tashkent in April 1942, when he was summoned to Kuibyshev to serve on the editorial committee of the newly-founded Eynikayt newspaper. 36 36 See “Lozovsky’s Cable to Aleksandrov concerning Eynikayt (April, 1942)” in Redlich, War, Holocaust and Stalinism, 192. Some of the articles he contributed as early as 1942 already moved beyond the despair, rage, and call to action of his first work and began calling not just for revenge, but for remembrance. “May the World Be a Witness” (July 25, 1942) calls specifically for bearing witness through writing, so that there is a record of Nazi crimes. “Remember” (September 5, 1942) implores its readers to do just that, even as the horrors of the Holocaust were still at their height. 37 37 David Shneer offered an insightful reading of both articles in “From Mourning to Vengeance,” 253-255. Bergelson made a similar plea for the importance of bearing witness in his fiction of the time, particularly in Night Became Day (Geven iz nakht un gevorn iz tog), his 1943 novella which literalizes the metaphor of an eye-witness by imagining the images left on the retinas of the victims. The novella is explored by Harriet Murav in David Bergelson’s Strange New World, 327-330 (digital version).

Hofshteyn was making similar early calls for remembrance while still in evacuation and not yet able to personally bear witness to the destruction he describes. At that time, he wrote the poem “Vi zayln fun shteyn zaynen fest…” (“Like pillars of stone are firm…”), in which he describes his situation far away from the traditional Jewish homeland. 38 38 Dovid Hofshteyn, “Vi zayln fun shteyn zahmen fest…” in Ikh gloyb (New York: IKUF, 1945), 22. “Yes, my country is still wide, is still large, / my country is important everywhere, / and home is wherever I go,” he wrote of his time in evacuation. Hofshteyn’s lines allude to “Wide is My Motherland” (“Shirokaia strana moia rodnia”), the patriotic Soviet song made famous in the 1936 film Circus. The song stands for the friendship of the peoples in the Soviet Union and represents the apparent ease he at least should feel while displaced in his own “homeland.” Nevertheless, “the city and the land still draw me to it,” he writes; he longs to return to the city which has been destroyed (tseshert) and desecrated (farshvekht) “with old Gothic script.” More than just a longing to return, what makes this poem fascinating for its time is its longing to remember. The “pillars of stone” from the poem’s opening line conjure up Biblical imagery from Genesis. Fleeing from Esau, Jacob sleeps one night on a pillow of stone and is visited by God, who promises “I will restore you to this land” (Genesis 28:15). Afterward Jacob consecrates the pillar of stone to mark and remember the place where God spoke to him and vows to return to it. Hofshteyn’s poem, in which he speaks about marking, remembering, and returning to his home city of Kyiv is thus a very Jewish way of marking place and remembrance. The use of Biblical motifs marks the tremendous power available to Yiddish literature at this time, free to reach into a uniquely deep reservoir of possible allusions.

These themes — the Jewish connection to the lands currently under occupation, the advocating for the leadership of Soviet Jews, and early calls not just for Jewish revenge but for Jewish remembrance — were all present in Hofshteyn and Bergelson’s early wartime work. They would all continue to be driving forces, albeit under new pressures, when the tides of war began to change in 1943 and the thought of returning became something not simply imaginable, but possible.

1943: Seeing the Liberation from Moscow

The end of the Battle of Stalingrad on February 2, 1943 is commonly seen as a turning point in the Great Patriotic War. After their defeat, the Nazi advance eastward was reversed and the Red Army began the process of re-liberating the occupied territories of Eastern Europe. Many members of the JAC were able to accompany the Red Army on their march westward gathering information, interviewing witnesses, and documenting the horrors of the Holocaust. The most famous example of this was The Black Book, compiled during the war by JAC members Vasily Grossman and Ilya Ehrenburg, though never published in its entirety in the Soviet Union. 39 39The Black Book included personal statements as well as documents such as letters, diaries, and descriptions from both Jewish survivors and non-Jewish eyewitnesses. Though some excerpts were published in both Yiddish and Russian in the Soviet Union, the book was never allowed to published in in its entirety due its insistence on the uniqueness of Jewish suffering during the Holocaust and war. Excerpts were sent abroad and published, but a full Russian edition did not appear until 2015. See the “Introduction” by Helen Segall, in the English translation, The Complete Black Book of Russian Jewry, translated and edited by David Patterson (Routledge: London and New York, 2017), xiii-xvi. Bergelson was eventually able to return to Moscow from Kuibyshev along with the rest of the JAC leadership and Eynikayt editorial board in 1943; from Moscow he too began to document the destruction, answering his own calls from the previous year to “Remember” and specifically to bear witness through writing. Though both Bergelson and Hofshteyn were unable to bear eyewitness, they began to encounter more and more of those who had, and were once again able to transform those impressions into creative works (be they fictional or journalistic in nature) from a distance. 40 40 Hannah Pollin-Galay notes what she describes as a “a clear division of labor in the work of witnessing: the escapees report what they saw, heard, and suffered in their towns and cities, and Ephsteyn [her example from among JAC members], their advocate and intermediary, testifies to the meaning and accounts on a higher moral level.” “Avrom Sutzkever’s Art of Testimony: Witnessing with the Poet in the Wartime Soviet Union,” Jewish Social Studies , Vol. 21, No. 2 (Winter 2016), p. 8.

Liberation provoked a complex emotional mixture of mourning and hope. David Shneer has explored how Bergelson managed to universalize the Nazi atrocities while simultaneously developing deeply Jewish nationalistic themes in his wartime journalism. 41 41 Shneer, “From Mourning to Vengeance.” Harriet Murav shows a similar development in Bergelson’s creative work written during the war and its immediate aftermath, in which his Soviet patriotism did not distract from his loyalty to the Jewish people. 42 42 Murav, David Bergelson’s Strange New World, 353 (digital version). Bergelson wrote three articles for Eynikayt in 1943 which reflect that hope for Jewish restoration. As the Red Army liberated city after city, writers described the fallout for an eager Jewish readership in both the Soviet Union and abroad; he wrote these articles in Moscow, each one dedicated to a specific city in Ukraine — Pereyaslav, Dnipropetrovsk, and Kyiv — cities that carried significant symbolic weight for the Jewish reader no matter where that reader might be located.

The first was an article marking the liberation of Pereyaslav published September 30, 1943 called “Sholem Aleichem’s City Liberated.” 43 43 D. Bergelson, “Bafrayt Sholem-Aleykhems shtot,” Eynikayt, 1943 September 30, p. 2. As is obvious from the title, the town was best defined for Bergelson by its most famous son. “There, in Pereyaslav, he learned to see with the eyes of his entire people,” Bergelson writes of Sholem Aleichem. The House Museum erected there in the first home of the father of Yiddish literature was “a symbol of the freedom of the Jews,” an ode to one of the triumphs of Jewish culture, and a place that, apparently, Jews and non-Jews alike happily visited. That the House Museum was destroyed by the Nazis was therefore not just an attack on Jewish culture, but on the entire notion of Friendship of the Peoples in the Soviet Union: “The city of Pereyaslav has always remained a symbol of the brotherhood of the Soviet peoples. And, as a symbol of brotherhood, it is dear to the heart of every Soviet citizen.” Bergelson achieves much in his brief article: not only does he combine the specific attack against the Jews with a more universal attack on Soviet ideals, he also draws worldwide Jewish attention back to its ‘birthplace,’ the same one as Sholem Aleichem’s, in an effort to show just how important it is to rebuild Jewish life and culture right there.

One month later he wrote “Dnipropetrovsk is Free Again!” about the liberation of that city, present-day Dnipro. 44 44 D. Bergelson, “Dniepropetrovsk iz vider fray!” Eynikayt, 1943 October 28, p. 2. “Another stone has been lifted from the heart of the Soviet country, and from the heart of the Ukrainian people, from the heart of every Soviet Jew,” he writes, universalizing the atrocities of the War and tying Jewish fate to that of their non-Jewish compatriots. The article does not focus however on the act of liberation nor on the present state of the city, which an on-the-ground reporter may have been better positioned to do; instead, written as journalism from a distance, Bergelson tells of Dnipropetrovsk’s past and its future. He describes its history as a centre of culture, home to many newspapers, theatres, clubs, and schools at which young Jews could find refuge and escape from the wretched existence of the shtetl. Though this was true even when it was known as Ekaterinoslav before the revolution, he says, “Dnipropetrovsk has had even more meaning for Jews in Soviet times.” This center of industry has been particularly important for the Yiddish writers, as it has created the type of educated reader who needs their work. Dnepropetrovsk is therefore a second example, for a Jewish audience both within and outside the Soviet Union, of how the Soviet state has combined the connection to Jewish literary culture with the empowerment of the Soviet Jews. Instead of focusing on the massive loss of life, he ends the article with a story of survival and a prediction for the future: Chaim Rivkin and Meri Zaydvaser had both been evacuated at the onset of the War, and now, “there are thousands and thousands of Chaims and Meris still living, and they will return to their hometown and they will build it anew.”

The last of the three articles dedicated to the liberation of a particular Ukrainian city was “Our Kyiv,” published November 11, 1943. 45 45 D. Bergelson, “Unzer Kiev,” Eynikayt, 1943 November 11, p. 3. Kyiv was the capital of Soviet Ukraine since 1934, Bergelson’s home for many years before the Revolution where he first found success as a writer, and from where the Kyiv Group of modernist Yiddish writers sprung. Its liberation was thus immensely important for reasons political, personal, and cultural. Just like he did of Pereyaslav and Dnipropetrovsk, Bergelson describes the meaningful place taken by Kyiv in both Jewish and Soviet identity, as a city so full of culture and vibrancy. 46 46 Shneer has also identified the Biblical references in this article which stresses the city’s specifically Jewish identity, and “view[s] the rebuilding of Kiev through the prism of Jewish prophecy.” “From Mourning to Vengeance,” 261. “Kyiv has once again become Soviet,” he concludes — but just as importantly, like all these cities, towns, and villages of Ukraine, Kyiv has once again become Jewish. All of these articles about Ukrainian cities were written in Moscow; it is as if his displacement has only heightened his sense of place and the genre of journalism from a distance has acquired a certain poetic poignancy which might have been more difficult for eyewitnesses themselves to draw out and give voice.

Hofshteyn was also permitted to move to Moscow around the same time in 1943, and the poetry he wrote during his time in the capital actually thematizes the sense of distance and turns into a powerful poetic tool to express the same kind of mixture of grief and hope that we see in Bergelson’s journalism. The poem “Mayn onheyb-heym” (“My First Home”), written in Moscow in January 1944, serves as a fitting example; Hofshteyn foregrounds the narrative distance by placing the poetic voice directly in Moscow.

47

47

Dovid Hofshteyn, “Mayn onheyb-heym” in Ikh gloyb, 50.

Though the poet is “in the noise of the capital,” his attention is turned fully to “my city, my first home, once a small shtetl on the Teter River.” He explains the picture:

Dort tsvishn feldun, ze ikh, hengt a breyter brik,

dos zemdl shpreyt zikh in der veytn klor un reyn

dort hobn zikh gekayklt teg fun yungn glik,

dort hot gerut mayn elter-elterns gebeyn.

There, between the cliffs, I see, a wide bridge hangs,

The grains of sand spread out in the distance, clear and clean,

There giggled days of young happiness,

There rest my grandparents’ bones.

Despite being in Moscow, the picture of the shtetl in his memory is so clear to him that he describes it as “seeing,” using the words “I see” as emphasis and as if he were indeed present. He is able to see the physical landmarks of the shtetl and to remember the entire span of life from childhood until death. For Hofshteyn, the distance has not dulled his view on his homeland, but sharpened it. He employs the metaphor of sight, in contrast to eyewitnesses who could use no such metaphor and in fact often claimed that words failed them when visually confronted with the horrors of the war and Holocaust. One of the earliest witness poems in Russian literature, “I Saw It” by Ilya Selvinsky, even includes the phrase “You can’t use words for this,” when trying to describe what was seen. Selvinsky thematizes speechlessness in the face of such horror, whereas Hofshteyn gives us both sight and speech from a distance. 48 48 Selvinsky’s poem is discussed by Harriet Murav in “Poetry After Kerchʹ: Representing Jewish Mass Death in the Soviet Union,” in Soviet Jews in World War II, 151-167, as well as Maxim D. Shrayer in I Saw It: Ilya Selvinsky and the Legacy of Bearing Witness to the Shoah (Academic Studies Press, 2013), Vasily Grossman also struggled to find the words necessary when he first set foot in liberated Kyiv and his hometown of Berdichev: “It’s hard to express what I felt and what I suffered in the few hours when I visited the addresses of relatives and acquaintances.” 49 49 Grossman wrote this in a letter to his wife in early 1944. A Writer at War: Vasily Grossman with the Red Army, 1941-1945, ed. and trans. Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova (New York: Pantheon Books, 2005), 254. For Bergelson and Hofshteyn in Moscow, however, the distance offers a protective layer that allows them creative expression in both journalism and poetry, and even provokes a new kind of aesthetics of far-away.

In the poem “Fun amol” (“Back Then”), Hofshteyn again situates the poetic voice in Moscow, the place of writing, in order to establish and thematize narrative distance, while still admitting his thoughts are of the shtetl and countryside. 50 50 Dovid Hofshteyn, “Fun amol” in Ikh gloyb, 52. “I always remember the fields,” he writes, referencing his own early poem from 1912, “In Winter Evenings,” the famous opening lines of which begin: “In winter evenings in Russian fields! / Where can one be lonelier, where can one be lonelier?” 51 51 Dovid Hofshteyn, “In vinter farnakhtn,” in Lider un poems, band eyns (Tel Aviv: Yisroel-bukh, 1977), 28. Hofshteyn then moves from the remembrance of the past to predictions of the future, and questions of continuity: “rivers will flow water, writers will write books and poets sing songs.” By establishing a congruency between rivers and words, Hofshteyn claims a connection between writing in Yiddish and the very landscape. He assures the reader that not only will they return to the land from whence they came, but that Jewish life and culture will continue there, rebuilt and flourishing once again in the USSR. Hofshteyn, as a writer and poet specifically, takes up the task of rebuilding that life and puts it upon himself.

1944: Return to Kyiv

In February 1944, Hofshteyn was invited to visit liberated Kyiv along with a group of other Yiddish writers so that they could survey the destruction first-hand. This finally gave him the chance to literally see what had been so vivid in his mind’s eye while in evacuation. He composed the poem “In aeroplan Moskve-Kiev” (“In the Airplane from Moscow to Kyiv”) about his journey there; by choosing to focus on the airplane ride, he once again thematizes distance as he is literally able to see the city from an aerial distance. He uses the last moments before being forced to face the destruction in order to interrogate his feelings of displacement and gives voice to the angst and fear raging inside him.

Kh’hob khadoshim gegreyt zikh, gegreyt zikh tsum shoyder, tsum vey,

shoyn khadoshim, az kh’shtik im, dem ershtn geshrey,

ven derzen kh’vell ot dortn dos alts, vos ikh veys –

undzer umglik, dem brokh in zayn tif, in zayn greys…

Un atsind kh’bin nit zikher, kh’bin nit greyt oykh atsind

in barirung tsu kumen mit vey un mit vind,

un mit eygene oygn fun noent derzen

ot di ale, vos zaynen ot dortn geven…

I have prepared myself for months, prepared for the shock, for the woe,

Already for months I have suffocated it, the first scream,

Our misfortune, the disaster in all its depth, in all its greatness.

And I’m not yet sure, I’m not yet ready,

To come into contact with such woe and such pain,

And to see up close with my own eyes,

All that was there…

52

52

Dovid Hofshteyn, “In aeroplan Moskve-Kiev” in Ikh gleyb (Moscow: Der emes, 1945), 50.

Though he has obviously heard enough about the Nazi atrocities to know what to expect in Kyiv, he is still not ready to see it with his own eyes. In his poetry from the year before, he was able to metaphorically “see” his hometown in all its pre-war peace and serenity, but once he is present in Kyiv he knows there will be nothing but “the disaster in all its depth” for him to comprehend instead of the full spectrum of life he was previously able to perceive. Being an eyewitness means he will lose the kind of distance that has allowed his thoughtful reflection for the last few years; this poem is the opportunity to extend and relive those last few minutes of a stifled scream before, he is sure, it will become too much to bear.

By all accounts it was indeed too much to bear; upon arrival Hofshteyn apparently wandered the destroyed city in a daze for entire days at a time. He learned that his mother and brother had been murdered at Babi Yar, but could not bring himself to visit the killing field. 53 53 Feyge Hofshteyn, Mit libe un veytik, 32. The loss of his own family illustrates how personal the Holocaust was for the Soviet-Yiddish writers; years later, in the 1952 trial of the JAC members, Bergelson himself acknowledged that many of them “were very grief-stricken. Many of their relatives had been murdered.” 54 54 “Testimony of David Bergelson (Court Record of the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, May 8-July 18, 1952),” in Stalin’s Secret Pogrom, 158. Hofshteyn’s poem can be read as a very personal reaction to trauma:a refusal to confront the scene of the traumatic event is a common trauma response. 55 55 The psychiatrist and psychologist Dori Laub has written extensively about the problem of the witnessing trauma, particularly regarding the Holocaust. The overwhelming nature of the traumatic event often silences the victim. See Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis, and History, eds. Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub (Routledge, 1992). In his study of Jewish combatants of the Red Army confronting the Holocaust, Mordechai Altshuler writes of a Jewish soldier who liberated Kyiv and then heard from an old man about the mass murders at Babi Yar. The soldier wrote in his memoirs: “I just left the old man standing there and started to run… I ran so that I wouldn’t have to see anything or hear anything.” 56 56 Quoted in Moderchai Altshuler, “Jewish Combatants of the Red Army Confront the Holocaust,” in Soviet Jews in World War II, 25. The same way that a victim or witness may choose to either voluntarily physically remove themself from a traumatic scene, or involuntarily remove themself through a physiological process like dissociation, Hofshteyn’s poem very consciously keeps its distance, situating the poetic eye above and away from what he knows will be emotionally overpowering as he provides an aerial depiction instead of an up-close and personal confrontation. 57 57 “Avoidance” and “Dissociation” are both common experience and responses to trauma according to Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services, Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 57. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4801 (Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

The poet and his wife returned to Kyiv permanently in summer 1944, and he did all he could to help the remaining and returning Jews in the city. He described two of them in a short piece called “Saved from the Hands of German Executioners.” 58 58 D. Hofshteyn, “Spasennye ot ruk nemetskikh palachei.” GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 92, 43. Hofshteyn describes spotting two young Jewish women on the streets of Kyiv, a sight not yet common in the waning days of war. One of the women is Miriam Shekman, who fled when the Nazis were approaching and joined a nearby group of partisans, and who therefore represents the heroic fate of the Jews in the Great Patriotic War; the other is Roza Gelman, whose story represents the other, tragic side of the Jewish experience of war. “In front of her own eyes, the Hitlerites shot her father and mother. She and her ten-year-old brother managed to hide with Russian neighbours… Roza’s brother died of hunger in her arms.” Though now still only 18 years old, Roza looks like an old woman already. Hofshteyn explains how he has helped her to become a nurse and how Soviet agencies have given her clothes, linens, and met the other material needs that have brought “the youth of a Jewish girl” back to her. In Hofshteyn’s picture, Soviet power can reverse time and literally rejuvenate the Jewish people. The same way the state has transformed the Soviet Jew since the revolution, he now shows his readership how youth, energy, and life will be brought back to a Jewish Kyiv after the war.

Around that same time, Hofshteyn wrote two more articles making calls to address the past. Like Bergelson, he was concerned with Jewish memory since the first days of the war, but the need for memorialisation became even more pronounced as it came to an end. His two articles demonstrate two drastically different memory needs for Hofshteyn and his Jewish audience. One, represented by the article “Sholem Aleichem and Ukraine,” was about reconnecting with and rebuilding the traditional Jewish culture of Ukraine and other places destroyed by war; the other, seen in his call for Germans to build “Museums of Shame,” was to remember the horrors of the Holocaust itself.

“Sholem Aleichem and Ukraine” was written just after the Great Patriotic War had ended and was sent abroad to the West. 59 59 D. Hofshteyn, “Sholom-Aleikhem i Ukraina.” GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 92, 35-37. Hofshteyn begins his article with the news that a memorial plaque has appeared in honor of Sholem Aleichem in front of his former home in Kyiv on Red Army Street — the symbolism of its name not to be overlooked. The article reminds us not only of Hofshteyn’s own previous encounter with “Tevye Not-the-Dairyman” in Ufa, but also of Bergelson’s lamentation that the Sholem Aleichem House Museum in Pereyaslav was destroyed by the Nazis in an affront to the Soviet notion of Friendship of the Peoples. That a new memorial is being constructed is a sign that the earlier raw anger is being channeled into construction and creativity, and that the hard memory work has begun. In her reading of Bergelson’s second wartime play Prince Reuveni, Harriet Murav has shown his similar attitude toward a new, Jewish future: Bergelson’s play focuses not on tragedy, but on the belief in the continuity of time and his hope for future Jewish life, which is being rebuilt by the hard work of restoring the past which he undertakes. 60 60 Murav, David Bergelson’s Strange New World, 339-348 (digital version).

Hofshteyn explains in his article that before the war Sholem Aleichem was published in twelve languages in the Soviet Union and read by millions of Soviet citizens. This establishes Sholem Aleichem as a shared figure in the cultural consciousness of the worldwide Jewish family as well as the Soviet one. By focusing on Sholem Aleichem’s literal place of residence as the site of memorial, he reminds his Western Jewish readership that the father of Yiddish literature was from Ukraine and that the Soviet Jews are next in that lineage, and thus natural and capable inheritors of the cultural legacy now shared between two families. He then provides a standard Soviet interpretation of Sholem Aleichem’s work, which sees it as a product of class struggle in Tsarist society. 61 61 For analysis of the typical Soviet reading of Sholem Aleichem, see Gennady Estraikh, “Soviet Sholem Aleichem,” in Translating Sholem Aleichem. History, Politics and Art, eds. Gennady Estraikh, Jordan Flnkin, Kerstin Hoge, Mikhail Krutikov. (Legenda: London, 2012), 62–82. For Hofshteyn, even though a character like “Menakhem Mendl is known to Jews everywhere Yiddish is read or spoken,” these works are tied geographically, socially, and politically to the specific context in which they arose. This context has given birth to a Yiddish-speaking Jewish diaspora all over the world, but is also one that led to revolution and to the Soviet power which has proven itself a worthy caretaker of its legacy, making Sholem Aleichem just as much a figure in the Soviet family and the perfect example of how those two families are related.

Unlike the first, which was directed toward Jews and discussed one of the triumphs of Jewish culture, Hofshteyn’s second call for memory action in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust was directed toward Germans, and asked them to remember their greatest atrocities. In “Museums of Shame,” he uses a harsh type of language similar to that of his own earlier essay, “The German Fool,” which made no distinction between the common German and the fascist, and to Bergelson’s in his 1944 article “The Germans Did This!” about the horrors of the Majdanek extermination camp. In just a few years Soviet policy would change; the Soviet press would place all blame for the worst aspects of the war at the hands of fascists, not Germans, but at this time Hofshteyn was clear just who was responsible, and what they needed to do.

We need a Museum of Shame in every city of the world, in every point of German population… We should use the same methods with the younger German generations that we use with cats and dogs: we should push their entire face into the horrible, disgusting filth that the German people have done during the War. 62 62 GARF, f. 8114, op. 1, d. 90, 463.

Hofshteyn’s article is strong and direct in its condemnation. The entire German nation is to blame and must carry this guilt and shame, working hard to “wash the filth from their hands.” He even suggests that every young German should be forced to take a special exam before they become a full member of society, proving that they know about the crimes of their parents and grandparents, and are truly aware of the contents of the so-called Museum of Shame. It is an angry and vengeful piece by Hofshteyn, a far cry from the kind of anxiety about confronting the crimes we saw earlier; nor is it even the same kind of mourning or memorial piece directed toward grieving Jews that he wrote as well. Here Hofshteyn has moved from grievance to accusation, and by suggesting that Germans be forced to look their crimes in the eye, he returns to the metaphor of sight, which was so painful for him upon his own return to Kyiv in 1944. He then moves beyond sight when suggesting that Germans have their faces pushed into their own filth: like house-training a dog, this multi-sensory experience requires recognition (and repulsion) activated by smell and touch as well. Despite the perspective he was able to acquire from a physical distance between 1941-1944, here he argues the temporal distance arising with the war’s end is not enough. Now Jews and Germans alike require sight and all their other senses, sometimes pleasant and sometimes painful, in order for a new type of memory to emerge.

Conclusion

Overall, Hofshteyn and Bergelson’s wartime writing demonstrates an attempt to create eynikayt or “unity” in the culture of the worldwide Jewish family. The fact that the only Yiddish journal permitted by the Soviet government during wartime bore that title shows just how acceptable such an attitude was deemed by the authorities. Before the war, the differences in historical development between Jews in the Soviet Union and those in capitalist countries were often stressed in the official, Marxist interpretation of Jewish nationality, but in this worldwide family, suddenly embraced and promoted in the pages of Eynikayt and elsewhere, the Soviet Jews were shown to take on the role of “elder brother,” in a way similar to the Russians in the Soviet family. To this end, the Yiddish writers stressed the way they maintained their authentic connection to the land and culture from which they sprung – Ukraine, a site not just important for Jews who could trace their roots there, but also certainly for Soviet power itself, still trying to cement power over this fractious and multiethnic “periphery.” It thus served the Soviet state’s own interests to allow the Jewish writers of the JAC a platform in which they demonstrated their connection to the land along with the ways that that the Soviet state had empowered the Soviet Jews, turning them into suitable leaders for their “dear brothers and sisters, Jews of the entire world.”

When Hofshteyn wrote that his “weapons are words” in 1942, he succinctly expressed that entanglement between Soviet power and Yiddish writers during wartime, and the extreme extent to which the relations of power had been renegotiated. It was an empowerment that had prepared and allowed Yiddish writers like Hofhsteyn and Bergelson to reach around the world and spread their Soviet-Yiddish culture — an outward reach, however, which was already coming to an end just as quickly as it had begun. Hofshteyn was arrested in 1948 and Bergelson shortly after him in January 1949 along with most other members of the Jewish Antifascist Committee; fifteen of those members were brought to a collective trial in 1952, which ended in their execution on the “Night of the Murdered Poets.” The trumped-up charges laid were vague and related to “promoting Jewish nationalism,” which seemingly amounted to nothing more than writing in Yiddish and taking an interest in Jewish concerns. Defending himself at the trial, Bergelson remarked on the abrupt change in permissibility: “There are many such expressions in literature, which were permitted at the time and were appropriate then, whereas now they would be considered highly nationalistic. There was an expression: ‘Brother Jews.’ I don’t see anything wrong with this expression.”

63

63

“Testimony of David Bergelson (Court Record of the Military Collegium of the USSR Supreme Court, May 8-July 18, 1952),” in Stalin’s Secret Pogrom, 157.

But by 1952 the Soviet nationalities policy and the atmosphere of the country had changed. The execution of the Yiddish writers is well-known and tragic, but looking at the moment from 1941 to 1945, before that other shoe ultimately dropped, speaks to the tremendous power of a weaponized Soviet-Yiddish literature during the war. It was a time when Soviet Jewish writers felt themselves not just a part of a worldwide family of “brother Jews,” but as its elder brother – still optimistic about a future unity and their place in it.