Apr 09, 2019

Georgia O’Keeffe. Abstraction IX, 1916. Charcoal on paper, 241⁄4 X 18⁄4 inches (61.5 X 47.5 cm.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1969 (69.278.4)

INTRODUCTION

This reading guide is part of a series designed to make our work accessible for use by educators in a variety of settings. We’d like your feedback to make these guides as useful as possible. Please write to pedagogy@ingeveb.org to tell us what you found helpful, what needed clarification, what you would like to see more or less of, and what texts or topics you would like us to produce guides for next.

If you are interested in creating a teaching guide for materials on our site, or if you are already teaching with materials on our site and have ideas to share, please also write to pedagogy@ingeveb.org.

For a PDF version of this teaching guide click here.

Approaches to Teaching Erotic Yiddish Poetry

I recently taught a course titled “Yiddish Literature in America,” and in it I asked my students to read a number of erotically charged poems by Anna Margolin, Celia Dropkin, and Malka Heifetz Tussman. In our course we attempted to situate these poems in relation to the political, romantic, lyrical, activist, experimental, and other concerns that other poetry and prose raised elsewhere in our course. I found that I had previously encountered resources, from my own training, for thinking through the political and communal motivations of Edelshtat, the romantic poetry of Rosenfeld, the aesthetics of the Di yunge poets, and the development of the In zikhistn beginning with their manifesto and moving beyond it. I tried to place the erotic Yiddish poetry in relation to the poetic lineages and concerns that I had learned marked the canonical trajectory of American Yiddish poetry. But within these concerns, there was limited space for thinking about the role of desire, of bodies, of the erotic as such.

So I asked around, and I have attempted here to build up a library of resources from scholars, artists, translaters, and teachers who share their experiences teaching erotic Yiddish poetry and/or discuss what they think are the most important ideas for teachers to consider when approaching these texts. In addition, I have included here a sample lesson of my own based on a selection of poetry by Troim Katz Handler. I hope that this compilation will be of use as those who teach Yiddish literature continue to expand the scope of themes and approaches to teaching Yiddish poetry.

I am grateful to all of those who participated in this piece. If you teach erotic Yiddish poetry and you have reflections, exercises, or recommendations to share, I hope you will write to [email protected]. Also, if there are resources you would like to see added to the suggestions for further reading, please send them along! I will be happy to add your work to this collaborative document.

Faith Jones:

I had pitched my Limmud Vancouver class in the most shameless possible way: “Come learn about the world of erotic Yiddish poetry your bubbe never told you about!” or words to that effect. Forgive me. I was just trying to sell books. But then I had to deliver on that class. So I chose the poems for the class simply by trying to maximize sexual variety. Then I made a PowerPoint menu of the sexual issue introduced by each poem, with a link to that poem, and decided to allow student choice to guide what we learned. We’d have a vote: which topic should we look at next? This was the slide:

The students did not disappoint. They jumped in at “Lust” and went only downwards from there. We never got back around to the top of the list. The poems we read were: “My Mother,” “My Hands,” “And Thirstily I Drink,” and “Suck” (all can be found in The Acrobat, the Dropkin collection I co-translated with the poets Jennifer Kronovet and Samuel Solomon).

About a third of participants knew Yiddish, so while we did look at the originals and talk about pure meaning, most of our conversation was about translation as a process. There was a student assistant from a local Jewish day school—getting credit towards his mandated volunteer hours for running technology at Limmud—and the poor young man could not look at me, or any of the adults in the room, as we discussed the snake imagery in “My Hands.”

Probably the most productive part of the conversation was about “Suck,” when we had to confront what Jesus is doing in this Yiddish poem about sadomasochistic sex. We wondered about how the crucifixion says something about bodies and pain, and the relationship of bodies and pain to God and spirit, and the relationship of God and spirit to sex and ecstasy. We didn’t necessarily agree with each other, but in the end we agreed that if you’re writing a poem about transgression, you might as well take it as far as you can.

I’ve given a number of seminars about Dropkin—those books aren’t going to sell themselves—but Limmud Vancouver was the most successful from a pedagogical standpoint. I suppose what I learned from the experience is this: if you are teaching adults, just put it all out there. We all have to deal with our feelings about our grandmothers having sex sooner or later. But if I were going to teach a whole unit or semester, I would temper it with other teaching styles. I would probably still start with something like this exercise, to break taboos and to unapologetically center explicit sexual topics. The downside (you will have noticed) is that the students get telegraphed the content and don’t get the joy of finding it themselves; and in turn, I miss out on their readings of the text, which could be radically different from, and better than, my own. So to follow up from a taboo-breaking exercise, I would move on to their own close readings of texts and get my assumptions out of their way. Ultimately, we are reading poetry here, so what matters is being able to really think about it deeply; to do that with sexual material we have to get past shame and titillation, and just read.

Faith Jones is a librarian in Vancouver, Canada. She completed an MA in which she investigated Yiddish culture in Winnipeg. She is co-translator of The Acrobat: Selected Poems of Celia Dropkin (2014), and is currently working on a collection of short stories by Shira Gorshman.

“Celia Dropkin: Bent Like a Question Mark” A work-in-progress concert by Book of J

July 30, 2018

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, Supported by New York City Department of Cultural Affairs

Jewlia Eisenberg and Jeremiah Lockwood:

Thinking about our work in progress…with Celia Dropkin: Bent Like a Question Mark

This past summer we were artists-in-residence at YIVO, beginning work on a hybrid archival/creative project on the work of Yiddish poet Celia Dropkin. Dropkin was a transgressive visionary who published her first poems in Yiddish around 100 years ago. She writes about desire and violence in a way that feels shockingly modern, causing queers, musicians, and revolutionaries to adopt her as our own. YIVO holds Dropkin’s papers.

Our project at YIVO had three main components:

1. We went into the archive at YIVO and read a lot of her unpublished works—to see what we wanted to use as song inspirations. She has a lot of excellent unpublished work, including some pieces that have the potential to make significant contributions to our understanding of her oeuvre.

2. We read Dropkin’s poetry with students. We offered them xeroxes of published and unpublished work. For published work we offered The Acrobat (Jones, Krovovet, Solomon), a book that includes translation with facing pages in the original Yiddish.

3. We composed a song cycle of ten pieces based on Dropkin’s writings, including settings of previously unpublished and untranslated works. Our final presentation at the end of our month of residency was a work-in-progress performance of these new songs as well as the screening of a short video we made of students at the YIVO Summer Program reading and discussing Dropkin’s work.

Dropkin’s poetry has a quality of performativity, acting on the reader and compelling a response that is embodied and immediate. Her startling and visceral description of sexual acts and the experience of longing and abjection in erotic relationships implicates the reader in a web of experience. Linda Williams talks about the power of genre art to act on the body; for example, the horror film elicits gasps. Dropkin’s work holds some of this quality of initiating physical response. The impact of her work makes her particularly fruitful for reading with students, in that it initiates a powerful and entrancing affective connection. At the same time, the focus of her work on erotic experience can be problematic for the classroom, bringing up subject matter that not all students will be comfortable discussing. For those students, framing it in a scholarly way may be particularly useful.

We found Zohar Weiman-Kelman’s reading of Dropkin to be a helpful opening for conversations with students. Dropkin’s poetry, as Weiman-Kelman says, “transgresses normative sexuality and thematizes powerplayand the explicit violence embedded in it.” Weiman-Kelman’s reading offers a chance to talk about fetishism and BDSM, and whether this work is part of what Elizabeth Freeman refers to as “a ‘reparative’ criticism that takes up the materials of a traumatic past and remixes them in the interests of new possibilities for being and knowing.” We also found the work of Dareick Scott (on abjection) and Ianna Owen (on failure) to be useful in framing poems about desire that is violent, ugly, and also transformative.

Questions that come up:

When is it interesting, moving, or useful to recite experiences of abjection?

By stating that one is experiencing pain, can we prevent others from defining it, deforming it?

Can there be a radical reclamation of abjection?

When is submission not powerlessness?

It can always be challenging to engage with work that is hardcore, as Celia Dropkin’s work can be. But if we want to make a world that does not idolize power, this is a good place to start.

Jeremiah Lockwood is a fifth year PhD candidate at Stanford University where he is working on a dissertation on young cantors in the Chassidic community in Brooklyn, NY. While working on his research and writing, Jeremiah pursues an active career as a musician; his band, The Sway Machinery, has performed on stages around the world.

Jewlia Eisenberg is a musician and composer working at the intersection of voice, text, and diaspora consciousness with ensembles Charming Hostess and Book of J. Her music is mostly released on Tzadik’s Radical Jewish Culture imprint; her installation work has been curated into the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco and the Museum of Peace in Uzbekistan.

![<p>Celia Dropkin, <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span><em>Dame in bloy</em>” [“Woman in Blue”]. Watercolor. In <a href="https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yiddish-books/spb-bilderfuninheysn00drop/dropkin-celia-bilder-fun-in-heysn-vint">Bilder fun <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>In heysn vint” [Pictures from <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>In the Hot Wind],</a><a href="https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yiddish-books/spb-bilderfuninheysn00drop/dropkin-celia-bilder-fun-in-heysn-vint">],</a> <span class="numbers">1959</span>. </p>](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ingeveb/images/dropkin.png)

Celia Dropkin, “Dame in bloy” [“Woman in Blue”]. Watercolor. In Bilder fun “In heysn vint” [Pictures from “In the Hot Wind],], 1959.

Zohar Weiman-Kelman

In her essay “The Yiddish Vocabulary for Sex and Love” Troim Katz Handler describes how her erotic poems come to her “in a mystical experience” (Handler 1996, 60). In teaching erotic Yiddish poetry, I aim to introduce the mystical-erotic experience that takes place not while writing, but while reading, and getting turned on by Yiddish poetry. In the moment of erotic arousal, the reader’s body becomes susceptible to the erotic interaction depicted in poetry, enacting what Carolyn Dinshaw describes as “touching across time, collapsing time through affective contact” (Dinshaw 1999, 16). The erotic mode of reading Yiddish poetry makes the flesh and blood of the world of the Yiddish past present. At the same time, being turned on by erotic materials in Yiddish activates not only the bodies of the readers, but also imagined bodies past, returning to them the corporeality that time, and the particular perils of Yiddish history, denied them.

In the corpus of erotic Yiddish poetry, the poems of Celia Dropkin (1887-1956) stand out for their overt expression of sexuality, and even more so for their unapologetic female poetic sexual agency and explicit sadomasochistic imagery. Dropkin’s poetry transgresses normative sexuality and thematizes power play, violence, and many forms of pleasurable pain. Fascinatingly, Dropkin does not take on a fixed position on the S/M dynamic portrayed across her poetry. In her poem “Odem,” the speaker plays the role of “top,” biting into the flesh of her consenting and indeed begging “bottom.” Yet in Dropkin’s most famous poem “Di tsirkus dame” [The Circus Lady] we can read a reversed version of the S/M power dynamic, where the female speaker erotically expresses her desire for pain, submission, and even annihilation.

Indeed, on the whole Dropkin’s poetry expresses a strikingly wide range of desires and positions vis-à-vis power and pleasure, vacillating between fantasies of extreme submission (“beat my hands/nail my feet to a cross/…/leave me deeply shamed”) and those of extreme domination (“my hands like snakes/that will choke you,” or “I’ve never seen you sleeping/I’ve never seen you dead”). Even within the use of a single image, Dropkin offers contradictory impulses; in the poem “A kush” [a kiss], she describes the speaker opening her lover’s blankets, kissing his chest submissively and thirstily drinking his blood, whereas in another untitled poem, she takes a knife to her own chest, and her lover lays his lips on her “wounded heart/drinks and drinks…”

Teaching these poems, I encourage my students to turn their ear not only to the erotic content, but to the form of the poem, and to the way it registers on their own bodies. Reading these poems, “our entire sensorium is activated in a synesthetic manner with one bodily sense translated into another” (Williams 1989), thus “viewing and hearing makes for a material experience of embodi-ment.” In the case of erotic poetry (much like the cases of visual pornography Williams is discussing) this translation from the poem to the body happens through both form and content. Specifically, the poem’s structure of address-- to “you --reaches out to hail the reader. Poetic devices of rhyming, repetition, alliteration, and other sound patterns sonically leave their mark on the reader. Finally, structures like enjambment render the reader dependent on the speaker, suspending her ability of interpretation across the poetic line (Agamben and Heller-Roazen 1999). Whether submitting to weakness or taking on a dominating position, Dropkin creates unique Yiddish poetics that succeed in materializing a lasting erotic charge. Teaching her erotic Yiddish poetry can offer consummation across time, promising new pleasure for Yiddish and poetry alike.

Zohar Weiman-Kelman is Assistant Professor in the Department of Foreign Literatures and Linguistics at Ben Gurion University. They recently published their first book Queer Expectations: a Genealogy of Jewish Women’s Poetry, and are now working on an online archive of Yiddish sexology as part of an exploration of the Yiddish history of sexuality.

Hinde Ena Burstin:

ON WRITING EROTIC YIDDISH POETRY

When I first wrote erotic Yiddish poetry, I had never read any erotica in Yiddish. So I had to be my own role model. I turned to expressing erotic desires in Yiddish when, for the first time in my life, I found myself in a place where I could be Yiddish and lesbian at the same time. I had the good fortune, at that time, to be living and dreaming in Yiddish. Writing about my fantasies — and realities — in Yiddish felt natural. I quickly discovered that Yiddish is a great language for writing erotic poetry. It has such zaftig, squishy sounds: oys, oohs, and aahs that are unafraid to be expressed with gusto and with passion. Giving voice to lesbian passion can also be a form of resistance against heteronormativity and the policing of women’s bodies. To name women’s body parts in Yiddish and own their desirability feels both delicious and seditious.

ON READING EROTIC YIDDISH POETRY

There is a way that Yiddish wraps itself around the tongue that makes you want to eat it up. The sensuous Yiddish sounds, along with an oral tradition of declaiming poetry with heart, passion, and nuance, makes reading erotic Yiddish writing a sheer delight. I often read my Yiddish poems to audiences where very few people speak Yiddish, yet inevitably, every time, at least one audience member will tell me that although they don’t speak a word of Yiddish, they understood everything I read. Reading erotic lesbian Yiddish poetry is both sexy and subversive. It cuts through the silence that has been imposed on expressions of lesbianism, a silence so deep that, despite growing up as a native speaker in a secular Yiddish-speaking community, I was 30 years old (and halfway across the world) before I learned the word for “lesbian” in Yiddish. Not everybody responds well to hearing erotic words spoken in Yiddish, especially where those words describe sexual activities between women. Reading to a disapproving audience can be disconcerting. I have learned to carefully choose the venues where I read erotic Yiddish poetry. This is not to say I will only read to approving audiences. It just means I make a conscious choice. Sometimes, you have to push the envelope.

ON TRANSLATING EROTIC POETRY

I find translating Yiddish erotica into English more challenging than other Yiddish-to-English translations, because of the way that sound can be so essential for setting and building the sexual atmosphere. As an example, I have not been able to translate my own poem “Eyn kuk” [“One Look”] into English in a way that satisfies me. I have made many attempts, with a range of different translational approaches, and have had friends try as well, but none of the translations has been able to capture the interplay of rhythm, sound, meaning, and musicality of the original.

Yiddish has a far freer syntax in terms of word order, which enables some delightful wordplay. This can be difficult to reproduce in English translation.

Translation from English into Yiddish can also present challenges. Many years ago, the brilliant writer Joan Nestle invited me to translate her erotically charged “Our Gift of Touch,” written for women in prison. (Bridges Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends, Vol 8, Nos 1 & 2, 2000, pp. 142-145). In “Our Gift of Touch,” Joan writes of moaning with pleasure. I was surprised to discover that I did not know how to say that in Yiddish. I looked in my dictionaries, but the only translations were for moaning as in complaining. I called my parents to ask them how to say “moan with pleasure” in Yiddish. They also didn’t know, so my beautiful Dad phoned all his friends to ask their opinions. My dad called me back with two options: “mruken” [a purring moan] or “brumen” [roaring]. So, I phoned Joan and asked, “For the sake of translational accuracy, when you come, do you purr or do you roar?” To this day, I can hear the smile in her raspy reply, “Honey, I roar.“

ON TEACHING EROTICA

With the right students, studying erotic writing can be a very positive experience. It is often relevant and relatable. It will certainly stimulate conversation. However, to my mind, teaching erotica needs to be a conscious choice based on the student cohort and class atmosphere. As a teacher, I need to be mindful of the students’ positioning. My Lubavitch students, for example, would be shocked to study erotica, finding it not tsniyesdik [modest, chaste]. Some undergrad students lack the maturity to deal with the subject matter respectfully. For others, studying erotic writing might not feel safe. For this reason, I don’t include erotic writing in the syllabus for my first semester with any group of students. I want to know the students before I share erotic writing with them. If it seems appropriate, I add it in. If students show sexist or heterosexist approaches, I do not include erotic writing in the course.

I have had some great experiences teaching erotic Yiddish poetry. Personal favorites for teaching are Fradel Shtok’s “Serenade” and her sonetn [sonnets] cycle, and Dina Lipkis’ “Fun yener zayt vant.” I also love teaching Rivke Kope’s “Dray”, because it leads to interesting Yiddish discussions about polyamory. I think it is important to ensure that the erotic poems selected cover a range of sexual desires. It can be very alienating for queer students if only heteronormative material is presented.

I always teach poetry in Yiddish and then in translation, even with beginners. Erotic Yiddish poetry presents wonderful opportunities to teach students about ways that poetry works with sounds to create atmosphere.

Like all writing, erotic poetry takes place in social contexts. I like to interrogate the power dynamics within and underlying the poems, and the social and political climate in which they were published. This can make for memorable lessons for students. Teaching erotica is a powerful way to subvert stereotypes about Jews and about Yiddish. It can also be a great way for students to bond and be inspired to practice their Yiddish outside of class!

Hinda Ena Burstin is a Yiddish writer and researcher who is passionate about retrieving forgotten works by Yiddish women poets and restoring their voices through readings and literary translations. She is coordinator of the Jacob Kronhill Program in Yiddish Language and Culture at Monash University, where she is also a lecturer in Yiddish language, literature, and culture. She is currently completing her PhD on Yiddish women poets of the 1920s. Her work has most recently been published in Pakn Treger, The AALITRA Review, and Women Writers of Yiddish Literature: Critical Essays. Yiddish is her mameloshn/native language.

Razel Zychlinsky, 1934, via http://www.zchor.org/

Diana Clarke

When I read erotic Yiddish poems, I am working on trusting the intuition of my body, tracing a lineage to find myself. In “Touching Time: Poetry, History, and the Erotics of Yiddish,” Zohar Weiman-Kelman writes, “As in the erotohistoriographic method, my reading of Yiddish texts “admits that contact with historical materials [...] may elicit bodily responses [...] I deploy erotic touch both as historical method and as object of study.” I have most often used Yiddish erotic poetry not to teach in the classroom but to teach lovers and friends that this lineage exists, to historicize and contextualize my own desires, and sometimes theirs. More broadly, I have invited Yiddish erotic poetry into Jewish organizing spaces to speak back to the popular American image of Yiddish as charming, fusty, and possibly insulting or acerbic, but not lush, human, sensual, or lived-in. Not dangerous.

For danger, I reach over and again to Rajzel Zychlinsky’s poem “bring me the blood of the enemy on your knife.” She writes:

bring me the blood of the enemy on your knife.

it may already be dried up, it will erase my heart.

it will erase the enemy who burns in my eyes,

and my gray hair will again turn black.

bring me the blood of the enemy on your knife,

i will kiss your hands long and piously.

Desire and erotic touch (“kiss your hands”) are bound up with violence, with justice, with a rejuvenation of youth (“hair will again turn black”). “Bring me”--it’s a command for the lover to do harm, and in so doing to stop the enemy. Who is the enemy? The reader can only trust the intuition of the body. In this poem, violence is care resulting in safety, and eros is violence’s reward. I use this poem to teach that justice can be intimate, that sex is no separate thing, that intimacy (the ability to ask, the ability to hold) is a protection against the harm others do.

The other erotic Yiddish poem to which I regularly turn is Anna Margolin’s “I have wandered so much.” Most recently, I used this poem in a seminar on archival intersectionality to expand and nuance the emotional elements of the Jewish sources I encountered at the Leather Archives in Chicago. In them, Jewishness was rarely mentioned explicitly, but it hovered at the edges: one essay on the Talmudic laws regarding slavery in the Spirituality and S&M issue of Prometheus, a prominent BDSM magazine of the early 1990s; the names Leonard Dworkin and Michal Daveed on the magazine’s masthead. Margolin’s poem, first published in the 1920s, reckons with the exhaustion of diaspora, of wandering, and how the narrator aches for submission: as grounding, containment, a place to land: “My bad blood, / the iron desire, / has chased me an entire lifetime. // Man of velvet and steel, / man, with quiet voice, / hover over me / shield me from the world / and from my own blood also. / Be kind.” Reading erotohistoriographically into the Leather Archive with the bodily information about Yiddish desire that this poem provides, I was able to help the class locate the insinuation of Yiddish embodiment in the erotic archive through my own present response to Margolin’s literary-historical evidence, even if only Jewish names, and not Yiddish desires, were made explicit in the collections themselves.

Diana Clarke is a doctoral student in the History Department at the University of Pittsburgh. They research the intersections of Jewish racialization, trauma, and whiteness in rural America, and are especially interested in discourses of assimilation related to sexuality and gender. Diana is also a 2018 Translation Fellow at the Yiddish Book Center, and their writing and translation has appeared in the Village Voice, Dissent, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and World Literature Today. Diana is the former managing editor for the In geveb blog.

Erotic Yiddish Poetry: A Sample Lesson

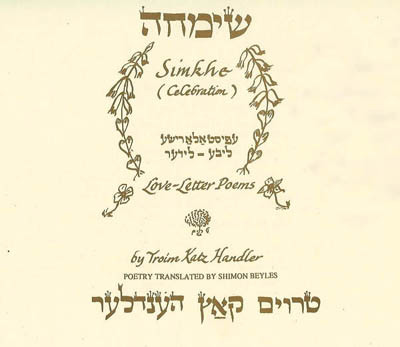

Earlier this year, Vaybertaytsh: A Feminist Podcast in Yiddish came out with an episode produced by Shoshke-Rayzl Yuni and Pearl Lipsky Krupit on the erotic Yiddish poetry of Troim Katz Handler, featuring the poet reading her own work and a conversation about Yuni and Krupit’s volume of translations of her poetry, Simkhe Volume IISimkhe Volume II. Handler’s work is bravely graphic in its portrayal of sexual matters, though as Handler herself insists, “the poems are not pornographic because they are in the context of love.”

In the Vaybertaytsh podcast, Krupit and Yuni explain the significance of this body of work. They explain that with these intimate, erotic love poems Handler preserves Yiddish phrases and ways of relating that often don’t make it to print. In Yuni’s introduction to Simkhe Volume II, she writes, “Handler is one of the precious few women in our time to write erotic poems with modern sensibilities and perspective, so openly free of restraint unlike previous generations who simply couldn’t or wouldn’t speak or write explicitly.” For Yuni, the poems not only have merit in and of themselves but also have an urgent purpose in preserving language: “We need examples of talk about love and closeness, even at times about private intimate matters. Without Handler’s work, perhaps we wouldn’t even have an idea as to where to begin. These poems are a crucial part of our goal to retain the language of our people.”

Vaybertaytsh published a pdf of several of these striking poems. Assign these poems to your students, and if they can understand Yiddish also ask them to listen to the podcast ahead of time. Then, proceed with the following questions.

Questions about the Poems:

Overarching Questions:

- Why is it important to write about sexual desire, in general? What are the politics of gender and language that might attach particular salience to Troim Katz Handler’s poetry?

- What was your experience reading this poetry? What about it was affirming? Uncomfortable? Exciting?

- How do these poems fit unto your understanding of genre? In what ways might you categorize them and what are they similar to (within and outside of Yiddish literature)?

- What are the audience considerations for these poems? Are they oriented toward popular audiences? Do you see them as private writings?

- Does it make a difference to your reading these poems, in terms of purpose, mission, and audience, that they were composed in Yiddish?

Questions about “Yeshue’le” / My Dearest Salvation:

- In the first stanza, would you describe the narrator as experiencing sadness/longing? Or sexual desire? Or both?

- Do you experience the turn from the first to the second stanza as surprising? Does it make you rethink the first stanza?

Questions for “Far mayn brivn-lubovnik” / For my Letter Lover:

- Does the narrator feel her heart has been wronged by the situation?

- Is she seeking the actual man, or the memory of him, or both?

- Why does she refer to the past as a gentler time?

Question for “Far dir, Simkhe, mayn morgn-shtern” / For you, Simkhe, my morning star

- “Earthquakes”: Why does the poet connect science and earth to sexuality? Do these metaphors help to elaborate her feelings or experiences?

- “Conflagration”: What do you notice about the sound of the poem? What mood or effect do the word endings in the first stanza create? Is there a relationship between this poem and the previous one?

Writing activity: After your students have discussed the poetry, invite them to write their own erotic poem (they do not need to share it with you!) in Yiddish or English. Once they have done this freewriting, ask them to discuss the experience of writing the poem. What makes writing or discussing sexual desire uncomfortable and difficult? What makes it liberating or exciting? What does it mean to approach these experiences or ideas in a classroom setting? Are there motivations (political, social, or otherwise) that they might want to address in writing an erotic poem, beyond the experiences or sensations of eroticism?

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red Canna, 1919, High Museum of Art, Atlanta

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Agamben, Giorgio, and Daniel Heller-Roazen. The End of the Poem: Studies in Poetics. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999.

Bernstein, Ignatz, and B. W. Segel. Jüdische Sprichwörter und Redensarten. Im Anhang: Erotica und Rustica. Hildesheim: G. Olms, 1969.

Burstin, Hinde Ena. “Akh, mayn beygl-bekerke” [“Akh, My Bagel Baker”]. Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 5 no. 1 (1995): 52-53.

———. “Ikh vil zayn a tursit” [“I Want to Be A Tourist”]. Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 5 no. 1 (1995): 54-57.

———. “Myriam’s Lid” [“Myriam’s Song”]. Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 5 no. 1, 1995, 58-53.

Dinshaw, Carolyn. Getting Medieval : Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

Dropkin, Celia. In heysn vint. New York: C. Dropkin, 1935.

Falk, Marcia. “Mother Nature and Human Nature: The Poetry of Malka Heifetz Tussman.” Lilith 17:, 20-23.

———. “With Teeth in the Earth: The Life and Art of Malka Heifetz Tussman: A Remembrance and Reading.” Shofar 9, no. 4 (1991): 24–46.

Fox, Sandra. “Smitten in Yiddish: Taytsh and Your Love Life.” In geveb, November 8, 2015.

Fruchter, Temim. “Embracing the Multiple: A Conversation with Zohar Weiman-Kelman.” In geveb, June 1, 2016.

Hellerstein, Kathryn. A Question of Tradition: Women Poets in Yiddish, 1586-1987. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014.

Katz Handler, Troim. “The Yiddish Vocabulary of Love and Sex.” Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 6, no. 1 (1996): 60-65.

Kope, Rivke. “Dray” [“Three”] in Toy fun shtilkayt: Lider [Dewdrops of Quiet: Poems]. Paris: Oyfsnay, 1951, p. 64.

Nestle, Joan. “Our Gift of Touch.” Bridges: A Journal for Jewish Feminists and Our Friends 8, nos. 1 & 2 (2000): 142-145.

Rogers, Janine. “Sex and Text: Teaching Porno-Erotic Literature to Undergraduates.” The Dalhousie Review 83, no. 2 (2003): 189-214.

Seidman, Naomi. “Talking Sex: The Distinctive Speech of Modern Jews.” Dibur, No 1 (2015): 51-59.

Singer, Isaac Bashevis. “Indecent Language, Sex, and Censorship in Literature.” trans. Mirra Ginsburg and B. Chertoff, ed. David Stromberg. In geveb, October 2015.

Torres, Anna Elena. “Celia Dropkin’s Adam.” Teach Great Jewish Books Resource Kit. March 2018. http://teachgreatjewishbooks.org/resource-kits/celia-dropkins-adam

Weiman-Kelman, Zohar. “Touching Time: Poetry, History and the Erotics of Yiddish.” Criticism 59, no. 1 (2017): 99-121.

Weiman-Kelman, Zohar. Queer Expectations: A Geneology of Jewish Women’s Poetry. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2019.

Williams, Linda. Hard Core : Power, Pleasure, and The “frenzy of the Visible.” Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1989.

Zucker, Sheva. “The Red Flower - Rebellion and Guilt in the Poetry of Celia Dropkin.” Studies in American Jewish Literature (1981-) 15 (1996): 99–117.