Aug 10, 2015

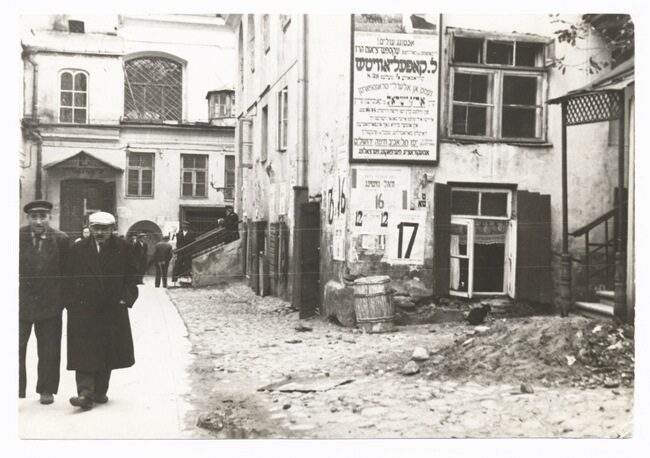

The shulhoyf, synagogue courtyard, Vilna, 1930s, showing a Yiddish advertisement for shipping agent L. Kopelovitsh. Source: YIVO Archives.

ABSTRACT

The “spatial turn” in the humanities has opened up new kinds of thinking about Jews’ relationship to place. Yet how can this approach — which focuses on the physically concrete — be applied to the field of Yiddish studies, which after all is defined by the intangible factor of language?

Is there such a thing as “Yiddish architecture”? I have encountered several skeptical responses to this question, yet I hope that as it occupies me it can generate some productive insights into the field of Yiddish studies and perhaps Jewish studies as a whole.

Many scholars have explored how Yiddish writers and artists sought to produce a modern culture that combined elements of tradition—in particular folklore—with the European avant-garde. Examples abound in literature, theater, and, to a lesser extent, the visual arts. Few have asked, however, whether there were parallels in the realm of design. In the years after the First World War, a battle played out in architectural circles between older historicist styles and the modern aesthetic championed by Le Corbusier in his treatise Towards a New Architecture (1923). Such debates were reflected in Zionist thinking about the proper appearance of new communities in the Yishuv such as the “first Hebrew city,” Tel Aviv. One idea I wish to explore is whether we can speak of a parallel “Yiddish architecture” or “Yiddish city” that reflects the attempt to create a modern Jewish culture in the Diaspora.

Even putting aside the issue of architectural style, it is clear that Yiddish-speaking Jews put their stamp on the environments in which they lived in a myriad of ways. The so-called “spatial turn” in the humanities has opened up new kinds of thinking about Jews’ relationship to place. Yet how can this approach—which focuses on the physically concrete—be applied to the field of Yiddish studies, which after all is defined by the intangible factor of language? One way to square this circle is to interrogate the role of language itself in shaping space. In my earlier scholarship I showed how the Jewish quarter of Vilna was marked as a distinct neighborhood through the use of Yiddish, which was not only heard in the streets but made visible on shop signs and advertisements. Efforts by various camps to promote or restrict Yiddish signage demonstrate that the significance of the language was legible—symbolically if not literally—to Jews and non-Jews alike. 1 1 Cecile E. Kuznitz, “On the Jewish Street: Yiddish Culture and the Urban Landscape in Interwar Vilna,” in Yiddish Language and Culture: Then and Now, ed. Leonard J. Greenspoon (Omaha, NE: Creighton University Press, 1998): 67-71. In this way residents and business owners created a kind of “Yiddish space” within the city.

While the narrow streets of Vilna’s Jewish quarter were lined with historic architecture, more modern structures were erected by Polish Jews to accommodate new communal and educational functions. The I.L. Peretz Folkshoyz (People’s House) in Lublin was established as a secular Yiddish school and cultural center. While its exterior was apparently planned without explicit Jewish references (it remained uncompleted in September 1939), I would argue that it sent a powerful message nonetheless. It hews closely to the tenets of the International Style advocated by architects such as Le Corbusier, thus underlining the forward-looking orientation of its progressive founders. These women and men emphasized how the building conveyed their commitment to the Diaspora nationalist principle of doikeyt or “hereness.” As Bundist Shlomo Mendelsohn (1896–1948) stated, “Peretz House in Lublin is—a symbol!” that “we are deeply rooted and entrench ourselves” in the local Polish environment, rejecting Zionist (and anti-Semitic) calls for emigration. 2 2Folkshoyz a.n. fun y.l. perets in lublin in gang fun der boy-arbet (Lublin: Boy-komitet fun folkshoyz in Lublin,1939): 5. Does the Peretz Folkshoyz, lacking Jewish stylistic markers but with implicit ideological overtones, qualify as Yiddish architecture?

These questions can, I hope, lead to fresh perspectives on two broader issues. Many criteria have been proposed for what makes a work of art Jewish, including the identity of the artist or intended audience, thematic content, or other more abstract qualities such as a proclivity towards abstraction. 3 3 See for example Stephen J. Whitfield, In Search of American Jewish Culture (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999): 1-31. While examples have been drawn from literature and to a lesser extent music and the visual arts, bringing architecture into the discussion can shed new light on this debate. To create a building, more so than a poem or a painting, necessarily involves a range of individuals to commission, design, and finance construction. Moreover, one may choose whether or not to read a novel or visit a museum. But a structure within a larger built landscape will inevitably become part of the daily experience of all those who inhabit, visit, work in, and pass by it. Thinking about architecture, in other words, encourages us to consider a wider range of actors who shape Jewish culture as both producers and consumers.

In addition, describing architecture—or cities, or space—as “Yiddish” raises the matter of the boundaries of Yiddish studies. Can an adjective referring to a language be applied to non-verbal cultural forms? Is “Yiddish music” or “Yiddish art” (or “Yiddish sandwiches,” as the sign in a Paris delicatessen would have it) a non sequitur, or may we consider Yiddish culture as encompassing all realms of expression distinctive to Yiddish-speaking communities? The founders of YIVO debated whether Yiddish scholarship encompasses work produced in Yiddish on any topic, work produced about Yiddish in other tongues, or both. 4 4 Cecile E. Kuznitz, YIVO and the Making of Modern Jewish Culture: Scholarship for the Yiddish Nation (New York: Cambridge University Press. 2014): 66-67. When writing a survey of the field of Yiddish studies a decade ago, I struggled over including historical studies of all Yiddish speakers or only those who consciously engaged the language and its culture. 5 5 Ibid., “Yiddish Studies,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies, ed. Martin Goodman (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2002): 541-71.

In an age of declining literacy among secular Jews, some have argued that Yiddish culture is becoming increasingly divorced from the Yiddish language itself.

6

6

Janet Hadda, “Imagining Yiddish,” Pakn Treger 41 (Spring 2003): 17-19; Jeffrey Shandler, Adventures in Yiddishland (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006): 184-185 and 191-192.

As we greet the appearance of a new journal—in English—I hope the concept of “Yiddish architecture” may help us think about the contours of the field of Yiddish studies and its future.