Jun 01, 2021

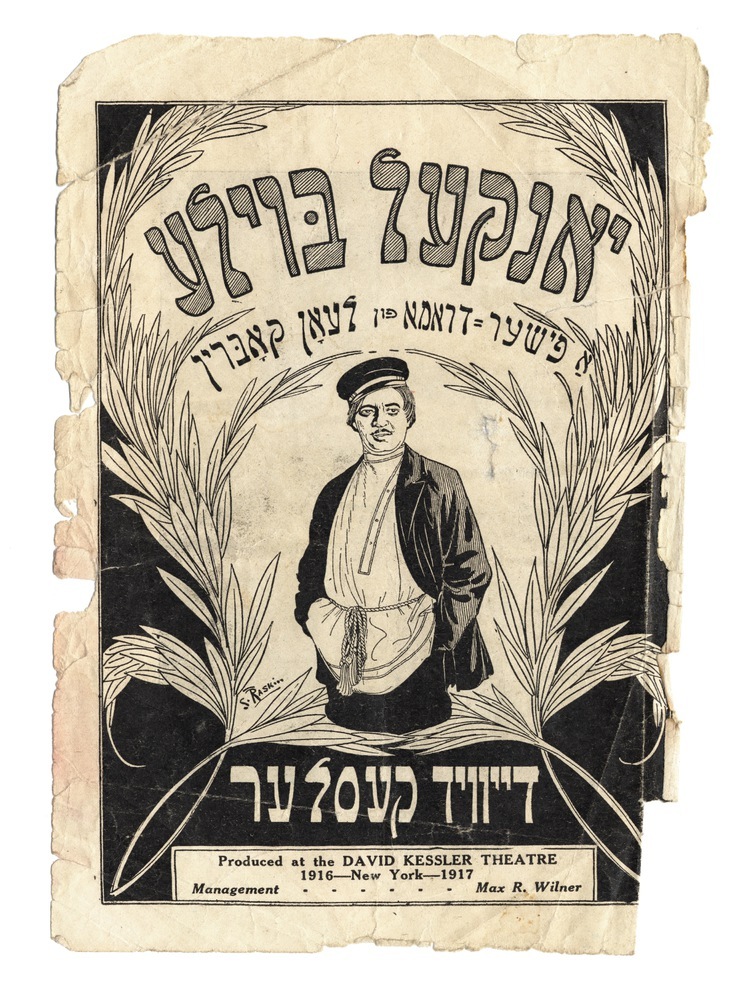

Caricature of actor David Kessler dancing as the title character in the stage adaptation of Leon Kobrin’s 1899 novella Yankl Boyle. From satirical journal Der groyser kundes, December 8, 1916, courtesy of the Yiddish Book Center.

A young man who is engaged to be married goes to his rabbi to learn about marital intimacy. Red-faced with embarrassment, he listens as the rabbi instructs him in how to properly perform the mitzvah of sexual intercourse with his wife. Finally, the rabbi asks the young man if he has any questions. Stammering, he asks if it is permissible to perform the mitzvah with the man on top. “Certainly, my son,” the rabbi reassures him. “This is a classic way of fulfilling the mitzvah.” The young man relaxes slightly and, although still blushing, continues with a second question. “What about with the woman on top?” Again, the rabbi reassures him: “Also perfectly acceptable, some people even prefer it. May you be fruitful and multiply!” The young man relaxes even more and begins to get more creative. He suggests several additional variations, and the rabbi enthusiastically approves of each one. Finally, with scarcely a trace of embarrassment, the young man asks if the mitzvah can be performed standing up. “Absolutely not!” the rabbi bellows. “It could lead to mixed dancing.”

When I told people I was writing a book about the Jewish taboo on men and women dancing, they frequently recalled this classic joke. In fact, the joke is so good that there are Baptist, Muslim, Mormon, Adventist, and Mennonite versions. Yet the ban on mixed dancing has a particular resonance in a Jewish context. References to the punchline appear frequently in contemporary Jewish popular culture, from a Nathan Englander short story to a viral Reddit thread, and saying something “could lead to mixed dancing” has become a lighthearted shorthand for all kinds of behaviors that are frowned upon by (Orthodox) Jewish communities. Although the joke mocks the logic behind rabbinic prohibitions, particularly the principle of “building a fence around the Torah” (according to which guidelines about religious practice should be made more stringent to prevent any possible transgression of Jewish law), it is popular among religiously-engaged Jews who use the punchline to signal their awareness of communal norms. Jokes about mixed dancing are an effective tool for poking fun at communal restrictions and for showing awareness of a social taboo.

For centuries, rabbis have forbidden Jewish men and women from dancing together, often in colorful terms. Grounds for the prohibition on mixed dancing include halakhic restrictions on men and women touching each other in general, and a lack of a precedent for this style of dancing in the Hebrew bible. The fact that these prohibitions frequently had to be repeated suggests that Jews often defied communal laws. They also found ways around them, such as by dancing holding onto opposite corners of a handkerchief to avoid touching one another directly, so that men––including Hasidic rebbes––could gladden a bride by dancing before her at her wedding. But not everybody stopped there. Whether for flirtation, fun, or simply because that was what everyone else was doing, young people still performed fashionable couple dances, which afforded them a cherished opportunity to interact without the involvement of their families or a matchmaker.

In my book, It Could Lead to Dancing: Mixed-Sex Dancing and Jewish Modernity, I show how writers have used scenes of transgressive dancing as a way of talking about the dramatic social changes that swept through Jewish communities across Europe and the United States between the Enlightenment and the Holocaust. Scenes of scandalous dancing are exciting, and they allow writers to entertain their readers while also making a political point about topics such as acculturation, secularization, sexual morality, and arranged marriages. Perhaps the most famous example of this motif is found in the American musical Fiddler on the Roof, where the revolutionary Perchik demonstrates his political radicalism by introducing mixed dancing to the shtetl of Anatevka. In my book, I focus primarily on what I call “mixed-sex dancing”––incidents where men and women dance together or interact significantly on the dance floor, and I demonstrate how such scenes are closely connected to concerns with gender roles, acculturation patterns, and changes in courtship norms. Yet this social mixing is rarely only about men and women dancing together. I have also found many dance pairings that transgress class, ethnic, or other boundaries–even if they do not necessarily violate the taboo on men and women dancing.

While researching my book, I collected a wide variety of entertaining dance scenes, in Yiddish and other languages. Many of them involved mixed-sex dancing. Others involved different, or additional, boundary crossings. I have shared some of these scenes in talks at KlezKanada and Yiddish New York. Many of these episodes found their way into my book. Others did not. Even though Perchik doesn’t dance in Sholem Aleichem’s original story “Hodl,” mixed dancing is a fascinating, delicious, and widely used Yiddish literary motif. Many Yiddish writers use dance scenes to add titillation, plot twists, character development, and social criticism to their fiction. The types of social mixing they describe might not be what you expect. For your reading pleasure––or as a potential warning––here are some of the best and most surprising actions in Yiddish literature that lead to mixed dancing.

Smuggling Horses Over The Prussian Border

In Joseph Opatoshu’s breakthrough 1912 novella Romance of a Horsethief (Roman fun a ferd ganef), set in Congress Poland, protagonist Zanvl celebrates a successful smuggling venture by carousing with his friends in a seedy tavern and dancing with his ex-lover Manya, a tavern maid. Never mind that he was thinking of turning respectable for his current sweetheart Rokhl, a nice Hasidic girl from the right side of the tracks. Or that he reconnects with an old friend Gradul, who introduces him to his seductive wife, Beyle, who has very liberal ideas about mixed dancing. In public. At a wedding. In front of Rokhl. This can only end well…

Fraternizing With The Polish Nobility

Once, court Jews would have been required to dress up as bears and entertain the guests at Polish noble balls. Or so says the dissolute nobleman Lucian in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s epic family novel, The Manor (Der hoyf, serialized between 1953 and 1955 in the Forward). Now, however, Lucian’s sister Helena attends a Jewish wedding and fraternizes with a Polish-speaking Jewish woman in a way that would have once been unthinkable, since a Polish noblewomen would not have been on such intimate terms with Jews or joined in their separate-sex dancing: “When the band struck up and the girls paired up with each other for dancing, Helena, requesting a mazurka from the musicians, threw a coin onto a drum as was the custom, bowed like a gallant before Miriam Lieba, and asked her to dance.”

1

1

Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Manor (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1967), 81.

In fact, Helena even befriends Miriam Lieba, invites her home, and introduces her to Lucian. Then he and Miriam Lieba elope. What happens to them next? Better you shouldn’t ask.

Getting A Fancy Secular Education

Education leads to family conflict in the novella Inconsistent (Nisht oysgehaltn), written by “Izabella” (pseudonym of Beyle Fridberg) and published in 1891 in the first volume of I. L. Peretz’s Jewish Library. Polia’s father indulges her in a bourgeois Russian education, with the assumption that once she has finished her studies she will come home and have a traditional arranged marriage, as her mother insists. Wanting to join her friends in their idealistic plans to become schoolteachers in Russian villages, Polia goes with them to a party celebrating their graduation, complete with mixed-sex waltzing, and it seems at first that her education has led her into just the secular world her mother feared. But despite her fondness for higher education, political idealism, and social settings with mixed dancing, Polia soon finds herself dancing with a group of women at her own traditional wedding.

Trying To Become American

Maybe you’ve heard of Abraham Cahan’s 1896 English-language novella Yekl: A Tale of the New York Ghetto, about immigrant life on the Lower East Side and the struggle to become American, or the 1975 feature film adaptation Hester Street (which has mostly Yiddish dialogue). In that case, you might be familiar with the story of Jake, who charms the ladies with his skill as a dancer at Joe’s Dancing Academy. Little do they know that he’s married, and it is very awkward when he finally sends for his wife Gitl. But did you know that while Cahan was trying to find a publisher for Yekl, he serialized a Yiddish version of his novella as Yankl the Yankee (Yankl der yanki, 1895-96)? Of the three versions, the Yiddish one focuses the most on female spectatorship in the dancing academy. It also develops a more polarized rivalry between the two female dancers who compete for Jake’s affection: his mild and gentle coworker Jenny (who, like Jake, comes from Lithuania) and the aggressive, dark-eyed Mamie, who comes from Poland.

Coming Home For The Holidays

Holidays can get complicated when older siblings who work in the city come home for some rest, relaxation, and matzoh––especially when the protagonist’s older half-siblings aren’t technically related to each other, and they’ve learned to dance in the cities. In Yehoshue Perle’s largely autobiographical 1936 novel Everyday Jews (Yidn fun a gants yor), the narrator’s older half-sister Ite (his father’s daughter) and older half-brother Yoyne (his mother’s son) come home for Passover. Ite works in a wealthy kitchen in Warsaw, and Yoyne is a salesman from Lodz. At first, Ite is turned off by the rude way Yoyne treats her father. But then he asks her to dance––or more accurately, he negs her into proving she can dance. Soon after this encounter, Yoyne and Ite begin a short-lived sexual affair, which awkwardly takes place in the family’s one-room house.

Hanging Out With Dead People

The over one hundred characters in I. L. Peretz’s expressionist 1907 play A Night in the Old Marketplace (Bay nakht im altn mark) represent a full panorama of Jewish society, both living and dead. So when the mixed dancing starts, it isn’t just a question of men and women dancing together; the dead also dance with the living. You can see a similar motif in the 1937 film version of Sh. Ansky’s The Dybbuk (Der dibuk), where modern dancer Judith Berg, who is also the film’s choreographer, performs a Dance of Death with the bride in the midst of a mixed group of dancing beggars. The dance is so intriguing, even the bride’s dead lover feels compelled to join in.

Illicit Sex

Yankl Boyle, protagonist of Leon Kobrin’s 1899 novella Yankl Boyle (later turned into a play with the same title), is not like the other Jewish men in his Russian fishing village. He struggles with basic Hebrew prayers. He speaks with a peasant’s accent. And, oh, can he dance! Yankl’s dancing skills help him win the affections of a Christian woman, Natasha: “In her eyes, he was a suitable beau with every virtue: handsome, healthy, well-dressed, and a tremendous dancer.” 2 2 Sonia Gollance, It Could Lead to Dancing: Mixed-Sex Dancing and Jewish Modernity (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2021), 89. Since the Jewish community doesn’t approve of their relationship, Yankl and Natasha prefer to dance and carouse with Christian peasants. In one dramatic scene, Yankl gets into a dance competition with another man. It’s all fun and games until people start gossiping about Yankl converting, his dead father’s ghost starts haunting him, and Natasha announces she’s pregnant.

Program illustrated by Saul Raskin for a production of Leon Kobrin’s “Yankl Boyle.” Courtesy of YIVO.

Walking In The Woods Minding Your Own Business

In Dovid Pinski’s 1938 short story “The Power of a Melody” (Der koyekh fun a nign), a Christian peasant encounters a group of Hasidim, whose ecstatic singing and dancing in the middle of the woods cuts right through a country path, blocking his way. At first the peasant is annoyed by this unexpected roadblock. He calls the Hasidim insulting names, mocks their dancing, and even lifts his coat and shakes his tukhes at them. The Hasidim are singing too loudly to notice, and the peasant continues on his way. But he finds his walk is less interesting without the dancing Hasidim, so he walks more slowly so that he can still hear them as long as possible. He starts to sing a folksong of his own, as loudly as possible, but he forgets the tune and starts singing the Hasidic melody. Finally, the peasant goes back and begins singing and dancing with the Hasidim. Recognizing the power of their faith, he crosses himself, and the Hasidim think that their shared dancing is a miracle.

Going Into The Kitchen To Get A Pickle

This one isn’t really about men and women dancing, but instead a practice round that goes horribly wrong. In Kadya Molodovsky’s 1942 novel A Jewish Refugee in New York (Fun lublin biz nyu-york), one of the most surprising forms of mixed dancing involves a man and a pickle. It doesn’t matter that Pinchas Hersh is practicing (with the pickle as his partner!) to dance a polka-mazurka with Chanke Mostovlianski, an actual woman. He still becomes a laughingstock who has to move to America to lose the nickname Pinchas Hersh-with-the-pickle. And Chanke? She refuses to dance with him.

Conspicuous Consumption

What point is there in arranging an illustrious marriage between a brilliant Torah scholar from a well-to-do family and a pretty girl from an equally wealthy family if you can’t show off the spectacle to all of your friends? This is the logic in Israel Joshua Singer’s 1936 family epic The Brothers Ashkenazi (Di brider Ashkenazi). It isn’t as if the bride is getting any other pleasure out of the wedding; Dinele would rather marry her new brother-in-law instead. And Simcha Meir, the groom, is busy plotting how to usurp his new father-in-law’s business. If this drama weren’t enough, the wealthy industrialists (bride’s side) and scruffy Hasidim (groom’s side) have very different ideas about how to celebrate the wedding. In fact, when the ragged group of largely uninvited Hasidim catch the acculturated Jews (a distinguished group of bankers and industrialists) engaging in mixed dancing in the women’s section, they trash the fancy hall and pour water on the waxed floors to prevent any more mixed dancing. Mazel tov!