Jan 13, 2023

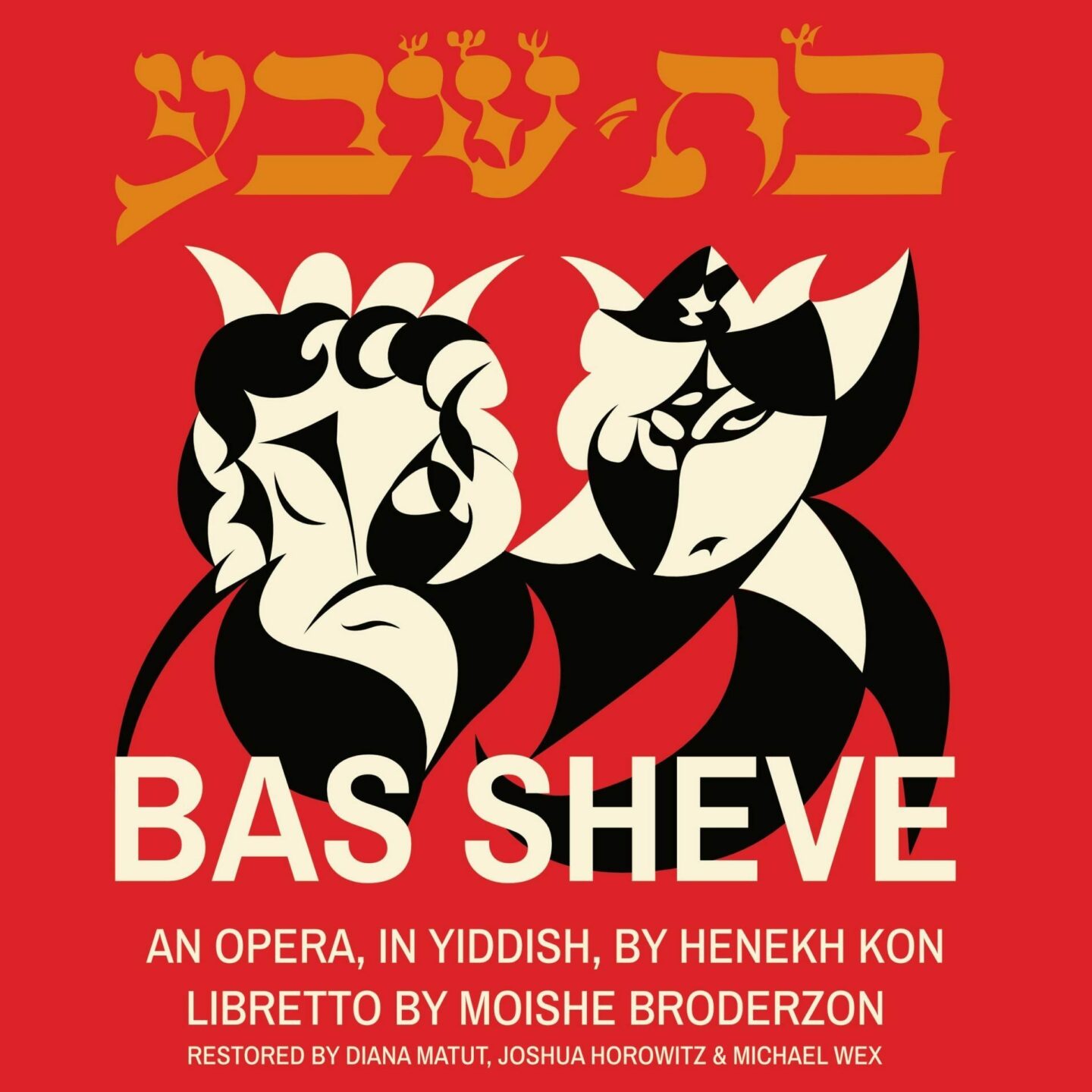

As the biannual Ashkenaz festival kicked off, so did the North American Premiere of Bas Sheve, a Yiddish opera, on August 31, 2022. Who would suspect that one could go to watch an opera in which a Yiddish-speaking Dovid Meylekh wore a man bun? Or that an opera would not be over until Bas Sheve sings? Originally by Henekh Kon with libretto by Moishe Broderzon, Bas Sheve premiered in Warsaw on May 24, 1924. Martin Luther University Halle Wittenberg professor of Jewish Studies Diana Matut rediscovered the score at a Yale University auction. When Matut found the score, there were sixteen missing pages. With a team consisting of composer Joshua Horowitz and librettist Michael Wex, Bas Sheve appeared reimagined and remastered for the twenty-first century.

Out of transparency, while I enjoy a night at the theater, my academic training does not lend itself to music criticism. Nonetheless, seeing this opera as an aspiring Yiddish scholar raised many questions for me. Without belaboring the minutiae of the technical questions, this opera evokes the perennial and, at times, uncomfortable place of Yiddish as diasporic kitsch. Far divorced from what was likely the serious desires of Kon and Broderzon to elevate Yiddish from vernacular to highbrow art, a 2022 Yiddish performance is layered with decades of Yiddish, or more accurately, Yinglish, symbolically becoming the language of comedians, an awkward punchline of a traumatic history on stage announcing a foreignizing presence. Inevitably, Yiddish will remain novel, kitschy, nostalgic, and even humorous when presented to a primarily non-Yiddish speaking audience, even if mainly an Ashkenazi one. In the seriousness of the transnationally collaborative twenty-first century revival, I walked away unsure if the excitement was about the opera on its own merits, its undoubtedly unique performance in Yiddish, or, indeed, the marriage of opera and Yiddish.

This line of questioning is not to diminish the care of the artists in recreating Bas Sheve, but rather to acknowledge some of the latent narratives with which such a project contends. Indeed, its appearance in the Ashkenaz Festival could not have been a more appropriate forum for a North American premiere. The festival is self-described as “originally… a showcase for Klezmer and Yiddish music and culture, the Ashkenaz Festival has evolved over the years into an eclectic showcase of global Jewish art and culture, encompassing not merely the traditions of eastern Europe, but also Sephardic, Mizrachi and Israeli culture, and all manner of cross-cultural fusion.” The venue was ripe for a showcase of Ashkenazi highbrow art, bookended by performances from an international cast of Jewish musicians and performers who flocked to Toronto for the festival.

After a heymish oneg-like opening night reception, Horowitz took to the stage explaining how he and Wex revived the once-lost opera. Wex is the author of Born to Kvetch (2005), among other books, and numerous translations of Yiddish literary works, but most relevantly, Wex translated The Threepenny Opera into Yiddish. Together Horowitz and Wex revived a long-lost manuscript. Wex, the librettist, had to lyrically fill in the blanks of Horowitz’s composition in a clear modern, and (as he described it) “psychedelic,” style. For example, at one point, the choir banged together rocks while intermittently shouting, making the new style hard to miss. According to the Bas Sheve website, Horowitz, in addition to his stylistic innovations, “chose to utilize two pieces that were composed later by Kon: His song, Yosl Ber, and the nign from the Polish film music Kon composed the music for, the Dybbuk.” Filling in the missing climax was an act of generational translation; Horowitz had in mind both fidelity to Kon and making his mark on the opera while orchestrating. Fortunately, for anyone who is interested in seeing the changes, the score (for those musically inclined), and the multilingual libretto, are available on their website.

While this was the North American premiere, the opera, in this contemporary iteration, was first performed in Germany at Yiddish Summer Weimar in 2019 (a preview of that performance is accessible online). However, with its reorientation in North America, the musicians and conductor were swapped from a local German ensemble for the UCLA Philharmonia directed by Neal Stulberg. As a result, the cast at this performance consisted of only Canadian soloists, featuring Jaclyn Grossman as Bas Sheve, Jonah Spungin as Dovid Meylekh, Marcel d’Entremont as Nosn, and Geoffery Schellenberg as the sheliekh.

At the beginning of the hour-long performance, the lights dimmed, and the four vocalists took center stage and sat in equally spaced-out metal chairs. The fixed position of the vocalists, who only rise to sing, relentlessly reminds the audience that this is not a fully performed opera. Dovid and Bas Sheve were flanked by Nosn, the prophet, and the sheliekh, a comedic antagonist to Nosn. The orchestra visible behind the soloists was complete with a choir. The choir began the opera with the refrain: “In bloe, tife malkhes-nekht, zayn vebung vebt der goyrl shlekht. [In blue, deep, royal nights, fate weaves its weave badly].” The leitmotif, while melodically recognizable, is altered to reflect the evolving drama throughout the opera.

The drama of the opera is not a surprise. After all, it is the biblical story of Dovid and Bas Sheve. However, what happens in the opera is perhaps best described as psychological midrash. Only a little happens in the story’s action, beginning after Dovid has sent Urye to the front line to die and after he has already impregnated Bas Sheve. Dovid’s first trial is guilt-induced insomnia. Yet, because the opera starts at the peak of Dovid’s downfall, one gets to explore the moral and psychological demons of Judaism’s most revered but problematic king.

The sixteen missing pages cut off after Nosn explains that Dovid will be forgiven but will suffer first, and the choir sings out the familiar refrain “meylekh Dovid khay vekayem [King Dovid lives and endures].”

From this point on, the climax is in the hands of Wex and Horowitz. During this part of the opera, Bas Sheve speaks, or rather, “sings” her sorrow as she mourns the loss of a son damned by the unambiguously violent conditions with which he was brought into the world. Horowitz’s composition ends, and Kon’s continues, after the child is proclaimed dead. At this point, the opera resolves and ends with the now familiar leitmotif, however, lyrically modified: “In bloe, tife malkhes nekht, firt knekht mit knekht a beyz gefekht. In tife, bloe malkhes nekht, far eybik rekht fun har! [In blue, deep royal nights, servant fights an evil battle against servant. In deep, blue royal nights, for the eternal privilege of the lord!]”

It is truly a dramatic moment in the plot where the original score cuts off and where the new score continues. Nosn tells Dovid that he will be forgiven, but first, he must suffer. There is a clear challenge in creating suspense from a story so canonized that the audience already knows how the drama ends. However, the music and space of the opera allow one to wonder how the events unfold, even if the outcome is known.

Image of Henekh Kon’s original score of Bas Sheve, via http://www.bas-sheve.com/.

The original staging of the opera in 1924 Warsaw certainly influenced the dialect Kon and Broderzon anticipated from their performers. When Horowitz made his introductory remarks, he explained a joke that was lost in translation and dialect. In Polish Yiddish Nosn is pronounced “Nisn.” The original 1924 audiences certainly would have heard the double entendre with the subtext that “nisn” also means sneeze. In an early scene, the sheliekh sneezes three times and sings, “Tsum dritn mol genosn!” announcing the arrival of Nosn. Even to the Yiddish-speaking audience today, the performer’s Yiddish resembles YIVO standard pronunciations. There were exceptions such as Dovid Meylkh’s German-sounding “ich,” which is unsurprising, considering that German is one of the primary languages of the operatic form. This slip, though it may sound jarring, does not change the meaning of the Yiddish or miss opportunities for wordplay.

The supertitles, created by Berlin-based translator and dancer Yeva Lapsker, were projected center stage accompanied by animations. Even if the soloists were not costumed and strutting across the stage, Lapsker’s clear eye for movement came through in the video projection which brought the audience into the world of the opera and simultaneously evoked the Yiddish avant-garde movement of the 1920s, which sought inspiration from bricolage, bringing together different mediums to make something that pierces through time. The performance, the composition with new lyrics, imposed itself onto and augmented the 1924 piece, which reaches back to an even older Biblical story. In the second half of the performance, the music and visuals deteriorate from Romantic and Classical paintings and ornamentation to psychedelic colors popping at the audience. The change is paired with the choir, essentially shouting, alerting the audience to the stark and sudden changes.

After the performance, there was a lively question-and-answer session. During this session, Horowitz and Wex spoke more about their process and especially the historical context of Bas Sheve. They remarked that both Kon and Broderzon were very prominent in Yiddish cultural life before the War, but this opera was a product of their early careers. Interestingly, Horowitz and Wex explain that while Kon and Broderzon could have revived Bas Sheve if they wanted to, they did not. It is possible that once the two were established in their careers, they began to see the opera as an early project that they did not want to see revived. The other possible explanation Horowitz and Wex gave is that nobody liked the opera at the time. Apparently, Yiddish papers did review the opera even though it did not run long at the time; however, this amendment about the Yiddish press was vague and did not account for its reception. Instead, Horowitz and Wex used the fact that Bas Sheve was reviewed in the Yiddish press to explain that even if reviewers did not like it, the opera was touted as proof that Yiddish could be a high culture language.

While during the opera the audience had to wait through half the performance before hearing from the titular character, this was not the case with the after-performance question-and-answer. Grossman, the soloist who played Bas Sheve, remarked that her work for Bas Sheve “felt like preparing for any opera. There is no reason why this [Bas Sheve] shouldn’t be available in any opera space.” Optimistic in keeping with the celebratory tone of the revival and premiere, she claimed that the only difference between this opera and any other is how it connects with her Jewish identity. Grossman did allude to the idea that the opera would have had a lasting place and capacity to act as a unique testimenant to Jewish culture in the general opera canon (and in the Yiddish canon) had the Holocaust not occurred. However, this idea is not corroborated by the pre-War life of the opera, where it originally had a short run, and instead, the creators put their energy behind other creative pursuits.

The final question worth considering from the discussion is: What makes the opera Yiddish, aside from the lyrics? Wex comically but bluntly retorted, “The fact that it’s managed to stay underfunded for a century.” The list of sponsors for a three-day run makes evident this fact. After all the speculation about why Bas Sheve had such a short run in 1924 and why Kon and Broderzon did not revive it, it seems that the answer could be that the opera then shared the same financial struggles as the Yiddish opera faces today.

Clips from the performance are on the Ashkenaz Festival YouTube page. There, one can get a glimpse of the world-class performances and visual experience.