Mar 07, 2021

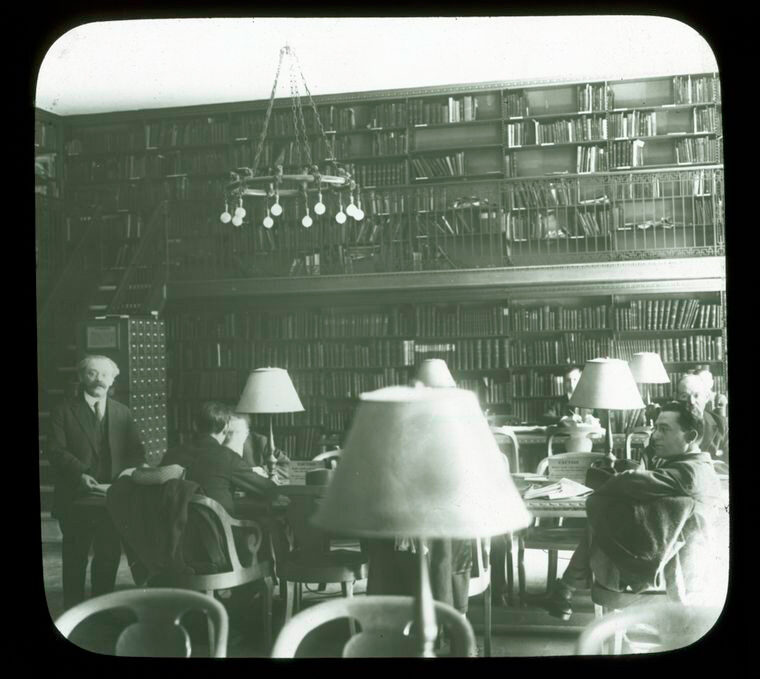

The Jewish Division, Room 217 in the Main Library of The New York Public Library (42nd Street and Fifth Avenue). Source: The New York Public Library.

INTRODUCTION

This is a companion piece to my article, “The Promises and Frustrations of Yiddish Studies Research during a Time of Quarantine: A Case Study,” in the Pedagogy section of In geveb. In that article, I describe the research tools and methods that I utilized while working on this essay. During the course of this modest project, which I began during the summer of 2020, I have had to rely on what is available online, both free and paid (accessible to me through my academic affiliation), supplemented only by printed books in my personal library and by occasional purchases from book dealers. I wish to express my deep appreciation for the assistance of my librarian colleagues Lyudmila Sholokhova and Amanda Miryem-Khaye Seigel, of the Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library, and Vanessa Freedman, at University College-London.

A Librarian on the Yiddish Rialto

Since retiring in 2018 from my position as Judaica/Hebraica Curator in the Stanford University Libraries, I have been pursuing research on Yiddish theatrical history. The fruits of my efforts to date include several posts and essays on the website of the Digital Yiddish Theatre Project (DYTP). In addition, also in connection with DYTP, I have been annotating a bibliography of over two hundred Yiddish plays.

Improbably, my work on the DYTP bibliography led to an exploration of the career of a reclusive, pioneering, and Yiddish-theater-loving Judaica librarian. This research in turn led me to the New York journalism of the leading theoretician of Socialist Zionism, who was in addition a passionate Yiddish philologist and literary scholar. The Yiddish daily and weekly press of New York City provided the bulk of the documentation about the personalities and institutions that are discussed here. The research revealed the tight nexus that existed over one hundred years ago between the small coterie of Eastern European-born Judaica librarians in the United States, who were children of the Haskalah; their philanthropic patrons, the oft-disparaged Yahudim of Central European background; and the largely male, Yiddish-speaking readers who frequented the important Jewish libraries of that era — amateur scholars, bibliophiles, literati, and journalists. Today, libraries can disseminate information on a scale that would have been unimaginable in 1920. Meanwhile, philanthropists have shifted their gazes to causes other than Judaica libraries. But the legacy of the earlier librarians lives on.

I first encountered the name Abraham S. Freidus as an intern in the library of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in early 1976. The internship program was run by the library’s Head Cataloger, Bella Hass Weinberg, and she mentioned the classification scheme that Freidus devised for the New York Public Library in her overview of library classification systems devised for Judaica collections. The Freidus classification has not been completely forgotten since then: In 2010, Vanessa Freedman, the Judaica librarian at University College London, devoted a major portion of her M.A. dissertation to it, and she spoke about it at the 2011 conference of the Association of Jewish Libraries.

1

1

Vanessa Freedman, The Maskil, the Kabbalist and the Political Scientist: Judaica Classification Systems in Their Historical Context (London: submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MA & Information Studies, University College London, 2010). In addition, Ms. Freedman spoke about the Freidus classification, along with two other Judaica classifications systems, at the 2011 conference of the Association of Jewish Libraries, and her presentation is accessible online: http://databases.jewishlibraries.org/node/17594 (accessed October 11, 2020).

In addition, I have long been aware that Freidus was the first Chief of NYPL’s Jewish Division (now called the Dorot Jewish Division). The door-stopper of a commemorative volume Studies in Jewish Bibliography and Related Subjects, in Memory of Abraham Solomon Freidus (1867-1923) occupied an honored place on my office shelves during my years as Curator of Judaica and Hebraica Collections in the Stanford Libraries, but it stood there mainly as a bibliographical monument.

2

2Studies in Jewish Bibliography and Related Subjects in Memory of Abraham Solomon Freidus (1867-1923) (New York: The Alexander Kohut Memorial Foundation, 1929).

Its pages are filled with erudite essays by a Who’s Who of Judaic scholars of its era, along with contributions by two of Freidus’s NYPL colleagues, Avrahm Yarmolinsky (Chief of the Slavonic Division, which I like to call “the NYPL’s other Jewish Division”) and Joshua Bloch (his successor as Chief of the Jewish Division).

3

3

Among the contributors are the historians Cecil Roth and Salo W. Baron, the Harvard philosophy professor Harry Austryn Wolfson, the Danish rabbi and bibliophile David Simonsen, the Hebrew scholars Israel Davidson, Bernard Wachstein, Isaac Rivkind, and David Yelin, and Freidus’s fellow librarians Alexander Marx, Israel Schapiro, and Aron Freimann (who, in the late 1930s, as a refugee from Nazi Germany, would come to work at NYPL). While at NYPL, Aron Freimann published A Gazetteer of Hebrew Printing, in the Bulletin of the New York Public Library, May, June, July, and December 1945. The Gazetteer was reissued by NYPL as a monograph, with revisions and additions, in 1946.

Bloch’s article “The Classification of Jewish Literature in the New York Public Library” offers an overview of important Judaica libraries and includes the detailed subject classification that Freidus devised for the Jewish Division’s rapidly growing collections.

My reintroduction to Freidus came about unexpectedly, in the course of annotating the DYTP bibliography of canonical Yiddish plays.

The bibliography includes tentative listings for a couple of works by the playwriting team of Rose Shomer Bachelis and Miriam Shomer Zunser, aka Di shvester Shomer — the Shomer Sisters.

4

4

Miriam Shomer’s father-in-law was Eliakum Zunser (1840-1913), aka Eliakum Badkhn, who was renowned for his wedding couplets. Zunser immigrated to the U.S. in 1889.

One of their big hits, “The Circus Girl,” was a vehicle for the very popular (and acrobatic) actress Molly Picon. With music by Joseph Rumshinsky, it opened at the Second Avenue Theater on September 15, 1928, where it enjoyed a 16-week run.

While annotating my entry on that play, my online search for bibliographical information led me to the Yiddish Book Center’s Digital Library, where I found a memoir by Rose Shomer-Bachelis, Vi ikh hob zey gekent (As I Had Known Them), which she self-published in Los Angeles in 1955. 5 5 Rose Shomer Bachelis, Vi ikh hob zey gekent: portretn fun bavuste idishe perzenlekhkeytn (As I Had Known Them: Portraits of Renowned Jewish Personalities) (Los Angeles: 1955). The chapter “Avrom Freydus” is found on pp. 89-90. Accessible online at: https://www.yiddishbookcenter.org/collections/yiddish-books/spb-nybc210269/shomer-bachelis-rose-vi-ikh-hob-zey-gekent-portretn-fun-bavuste-idishe-perzenlikhkeytn (accessed October 11, 2020). There, her arresting pen portrait of Abraham Freidus is nestled alongside reminiscences about such iconic authors as Morris Rosenfeld, Eliakum Zunser (Miriam Shomer’s father-in-law), Naftali Herz Imber (author of the future Israeli anthem “Ha-Tikvah”), Peretz Hirschbein, and Solomon Bloomgarden (Yehoash), the theater luminaries Abraham Goldfaden and Bertha Kalisch, and members of the Shomer Sisters’ family (their father was the prolific author of Yiddish pulp fiction and plays Nokhem Meir Shaykevitsh (1846-1905), also known by the pen name Shomer).

In her brief and affectionate account of Freidus, Rose Shomer sketched out his personal and professional idiosyncrasies. First, his physical attributes: “average height, fat, with a round, smooth face and an even smoother, shaved scalp.” Next, his appetite: “He loved to eat a lot – two portions of each dish that he was served. But he would skip dessert in order to lose weight.” Upon meeting an acquaintance, rather than shake hands Freidus “offered one finger – his index finger.” He seldom opened his mouth to speak, preferring instead to listen, especially if he enjoyed the sound of the interlocutor’s (or, at a lecture, the speaker’s) voice. (The Yiddishist intellectual Chaim Zhitlowsky was a Freidus favorite.) Though Freidus never married, “he liked girls with black hair and dark eyes; [but] he avoided blondes and redheads like the plague.”

Freidus’s first love was his work as a librarian. When the NYPL administration offered to give him a raise, “he sharply protested: ‘Buy books with the money, instead.’” He was deeply devoted to the Jewish Division’s patrons: “He kept everyone in mind and remembered what kind of information each person needed. In his spare time, he would read a variety of newspapers in a range of languages and prepared clippings for various people.” Case in point: On one occasion, Rose Shomer “asked him a question about spinach, so Mr. Freidus provided me with a year’s supply of clippings about that vegetable.” Each evening, after the library closed, he repaired downtown to “the boisterous Café Royal on Second Avenue, which was the gathering place for writers, actors, and others. Freidus would sit by himself at a small table until late at night, not speaking with anyone, and make clippings from newspapers.” To him, the café’s hubbub provided a welcome “balance to the silence that reigned all day long in the library.” Rose Shomer concluded her affectionate account of Abraham Freidus as follows: “A devoted friend, a good person, he lived alone [and] died alone, on a busy street in New York.”

“Pillar of Fire”: Ber Borokhov on Abraham S. Freidus

Virtually every contemporaneous write-up of Freidus – and there were quite a few – confirms Rose Shomer’s capsule summary, which she published more than three decades after his death. I was able to track down many of these articles through a simple keyword search in JPress, using the English and Hebrew / Yiddish spellings of his surname. Given the imprecisions of the JPress OCR engine, it helps that “Freidus” (פריידוס) is a short and uncommon name in both alphabets. In addition, the Freidus memorial volume includes a bibliography of articles and obituaries about Freidus, some of which I was able to access online via JPress.

One of the most perceptive journalistic pieces about Freidus that I found is by Ber Borokhov. Appearing in the May 22, 1917, issue of the New York Yiddish daily Di varhayt (Warheit), it bears the biblically inspired title “Der omud-ha-esh fun der idisher bikher velt” (The Pillar of Fire of the Jewish Book World”).

6

6

B. Borukhov, ““Der omud-ha-esh fun der idisher bikher velt,” in Di varhayt (Warheit), New York, May 22, 1917. Accessible online via the Historical Jewish Press Project / JPress.

Borokhov’s political writings fused the ideals of Zionism with those of socialism, and nowadays he is remembered as the leading theoretician of the Po‘ale Tsiyon (Poale Tsien) movement. But he was also a habitué of the great research libraries of Europe and the United States, where he pursued his scholarly endeavors. He was working on his magnum opus, a multivolume history of the Yiddish language and its literature, when his life was cut short in December 1917 at the age of 36. Indeed, in Yiddish Studies circles, Borokhov is revered as the pioneering Yiddish scholar who set the research agenda for this nascent field in his 1913 essay “Di oyfgabn fun der yidisher filologye” (The Aims of Yiddish Philology) and the accompanying bibliography “Di biblioteyk fun dem yidishn filolog” (The Library of the Yiddish Philologist).

7

7

Both of these essays were published in Der pinkes, ershter yohrgang [5]672, redaktirt fun Sh. Niger (Vil’no: Vilner ferlag fun B. A. Kletskin, [5]673 [1912/1913]); see: B. Borokhov, “Di oyfgabn fun der yidisher filologye,” cols. 1-22, and “Di biblioteyk fun dem yidishn filolog,” [part 2], cols. 1-65. They are also included in Nakhmen Mayzel’s compilation of Borokhov’s writings on Yiddish, Shprakh-forshung un literatur-geshikhte (Tel-Aviv: I. L. Peretz Publishing House, 1966). Both Der pinkes and Shprakh-forshung un literatur-geshikhte are accessible online, via the Yiddish Book Center. For background and perspectives on “Di oyfgabn…” see: Dovid Katz, “Ber Borokhov, Pioneer of Yiddish Linguistics, in Jewish Frontier, vol. 47, no. 6 (1980), pp. 10-14; Barry Trachtenberg, “Ber Borochov’s ‘The Tasks of Yiddish Philology’” Science in Context, vol. 20, no. 2 (2007), pp. 341-379; Miriam Schulz, “For Race Is Mute and ‘mame-loshn’ Can Speak,” in Judaica Petropolitana, vol. 5 (2016), pp. 98-127, online at: https://judaica-petropolitana.philosophy.spbu.ru/Archive/issues.html (accessed October 31, 2020).

“Biblioteyk” (ביבליאָטייק) is a transliteration of Borokhov’s spelling of the Yiddish word for “library”; for him, reform of Yiddish orthography was an idée fixe.

Accompanied by his wife and young daughter, Borokhov arrived in the United States in late 1914, several months after war had broken out in Europe. He reunited in New York City with his immigrant parents, who had settled there. Borokhov stayed in the U.S. until the middle of 1917, when he returned to Russia to agitate on behalf of the Po‘ale Tsiyon party. During his two and a half years in the U.S., he threw himself into the Labor Zionist movement’s activities and he served as editor of the party’s organ, Der idisher kem(p)fer. In addition, he was in frequent demand as a lecturer at Po‘ale Tsiyon gatherings in New York and elsewhere.

For Di varhayt, Borokhov contributed articles about Zionism, world politics, Yiddish literature, and the Yiddish theater, along with a regular book-review column. Somehow, he also found the time to pursue his research projects, and that is what brought him to NYPL’s Jewish Division and several other Jewish libraries in the U.S., which were the focus of a second piece by Borokhov in Di varhayt. His tribute to Freidus coincided with the librarian’s fiftieth birthday – an event that served as the occasion for a surprise party that was held at the Upper West Side residence of George and Rebecca Kohut on May 1, 1917. (Borokhov was not present at that celebration.) The article appeared while Borokhov was in the throes of preparations for his return to Russia, a fact to which he alluded:

Many of those who devote themselves to scholarly studies, whether systematically or casually – scholars, journalists, and artists – have often had the opportunity to tap Mr. Freidus’s knowledge and friendliness. And wherever they might eventually wind up – wherever fate might toss them – one of their best memories will always sweep them back to the quiet confines of the Jewish Division of the New York Public Library. For here Mr. Freidus reigns and serves as the sovereign over the books and the friend of each and every researcher.

Like others who wrote about Freidus, Borokhov compared his subject’s attachment to the library’s clientele to that of a parent overseeing “a helpless child; he will do everything to make you feel that you are not on your own but are in your father’s home. He is concerned that your work will be blessed with good fortune – and he wants no recognition for his efforts. He is [even] insulted by your gratitude.” In addition, Borokhov discerned the professional qualities that lay behind the librarian’s nurturing of his patrons. Not only had he built up a collection of 25,000 volumes during the course of his twenty years of service, but he had established order out of the bibliographical chaos that he encountered when he was appointed as the Jewish Division’s first Chief in 1897.

For today’s users of online library catalogs and bibliographical databases, Borokhov’s description of the Jewish Division’s card files serves as a useful reminder that the card catalog was the search engine par excellence of the analog era in libraries. It was the state of the art. As Borokhov wrote, “Who has not heard of Mr. Freidus’s catalog?” To him, it was one of the marvels of the age: “The catalog is a system of cabinets, filled with 120,000 cards and with tens of thousands of newspaper clippings… There, in the catalog, you have everything relating to Jewish matters. If you want to know your own biography or the address of your famous friend, you will find it there. If you are searching for a Jewish organization somewhere – say, ‘Anshe Boiberik’ – just consult Freidus’s catalog, and there you have it.”

Borokhov directed his newspaper readers’ attentions to another, equally critical aspect of Freidus’s organizational genius: “And then there is the classification!... This is Freidus’s [alphabetical] letter-system, which the greatest authorities in library science consider to be wondrous for its simplicity and comprehensiveness.” He provided a few concrete examples of how a shelf classification works: “If you’re looking for something that has to do with the Hebrew Bible, go to the ‘D’ shelves. If you’re looking for Jewish history, take the shelves marked ‘X.’ If you want mame-loshn, inquire within the shelves marked ‘T.’ And so forth.” Further, Borokhov noted, each main letter within the classification system included numerous subdivisions, for a grand total of 500 classes and subclasses within what would later be known as the Freidus-Billings classification. 8 8 The outline of the Freidus classification was included in the memorial volume and, with modifications, is now accessible online: http://billi.nypl.org/classmark/*P/about. Each of the main letters delineated by Borokhov is preceded by *P. (Freidus shared credit here with John Shaw Billings, who had been appointed as the NYPL’s first Director in 1895.)

For a large library, an organizing principle is of course indispensable; what, then, of its holdings? Borokhov praised Freidus’s accomplishments on that front as well: There were the Jewish Division’s 4,000 periodical and newspaper volumes; 3,000 volumes of the Tanakh (and portions thereof) and its commentaries and translations; 2,000 volumes in Yiddish; 500 volumes on the Land of Israel; 2,000 volumes of responsa. “In New York, you can get everything that is published in America and almost everything from Russia, thanks to our friend’s two decades of collecting.” Borokhov described some of the Jewish Division’s rarities, incunabula (books printed before 1501), manuscripts, and fine editions which Freidus had shown him – further evidence that this “lonely, eccentric person,” as Leonard Singer Gold characterized him, was a master of his craft.

Borokhov concluded by conveying his impressions of the “national characteristics” of the world’s research libraries and their custodians:

Go to a library in Italy and you are immediately seized by the air of centuries of inborn refinement, the elegant atmosphere of a Renaissance church. Visit a library in Germany and you encounter the cold precision of a police station; you don’t quite know why you need to be in the library – did you want to study there, or did you commit a felony? In France a library is somewhat neglected and in disarray, with people chatting loudly and amiably all around you, the way things are in Paris. Upon entering an Austrian library, you encounter a mishmash of the German police spirit and Slavic disorder. In England, there is cold politeness, where the library is a gigantic engine that serves you with the friendliness of a machine and the staff are merely small cogs that move according to the clock’s ticking….

A German librarian gives you the books unwillingly; the English [librarian], with the cold, apathetic attitude of an indifferent person; the Italian, with the easy-going friendliness of a monk who is satisfied to observe a new person who has come from afar.

Whereas, at the New York Public Library, “Mr. Freidus has created the prototype of a Jewish library: Talmudic acuity and the most precise classification, genuine Jewish warmth and an insistent manner of service that is authentically Jewish.” By this, Borokhov was alluding to Freidus’s practice of catering to his regular readers’ needs by personally providing piles of books and wads of clippings that he felt would further their research interests or journalistic assignments. Borokhov did not mention Freidus’s political views or affiliations. Indeed, Freidus stood apart from the ideological quarrels of the yidishe gas; whenever he was queried about his politics, he would respond that he was a librarian.

By defining the Jewish Division as the quintessential “Jewish library,” Borokhov was only half right. If one is to speak of a library’s “national characteristics,” then the NYPL’s Jewish Division in the Freidus era was also – and above all – an American institution, albeit one with an Eastern European Jewish tinge. Peter Wiernik described Freidus as a one-time prodigy in full command of the Jewish textual tradition, who in his youth absorbed the teachings of the Haskalah and emerged as an adamant freethinker. Just a few years after immigrating to the U.S., the erstwhile ‘ilui Freidus enrolled in Pratt Institute’s library school, one of the first training grounds for professional librarians in the United States, and he graduated in 1894.

9

9

For historical background on the Pratt Institute’s Library School (now called the School of Information), see: https://www.pratt.edu/academics/information/about-the-school/history/; and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pratt_Institute_School_of_Information (accessed October 11, 2020).

Both by virtue of his formal education in librarianship and his experience as a staff member at one of the nation’s foremost research and reference libraries, Freidus absorbed the service ethos and organizational methodologies of American librarianship. And the shelf classification that Borokhov praised so highly was but one small segment within the NYPL’s ramified classification scheme – after all, the Jewish Division itself was but one “cog” in a much larger American “machine.”

“Who Will Run the Jewish Division?”

To be sure, the “Jewish” qualities that Borokhov and others remarked upon in Freidus’s domain in Room 217 of the Forty-Second-Street Library were undeniably personified by the Jewish Division’s Riga-born Chief and much of its clientele. A couple of months after Freidus’s sudden demise, the newspaper Der tog / The Day ran two articles devoted to the future of the Jewish Division, each of them highlighting the Division’s distinctive atmosphere, while drawing different conclusions as to its virtues. Looming behind both of these articles was the suspicion that a power play was afoot at NYPL to have the Jewish Division absorbed by the Oriental Division, which was headed by the Columbia University Semitics scholar Richard Gottheil. Yiddish journalists did not consider Gottheil (son of the Prussian-born Reform rabbi Gustav Gottheil) to be terribly sympathetic to either the late Abraham Freidus or a separate Jewish Division.

The first of the two articles in Der tog, “Who Will Run the Jewish Division?” was by the Hebraist intellectual Reuven Brainin. 10 10 Reuven Brainin, “Ver zol farvalten di idishe opteylung? A frage vegen der shtodt-bibliotek, vos iz negeye di gantse idishe inteligents,” in Der tog (The Day), New York, December 20, 1923. Accessible online via the Historical Jewish Press Project / JPress. Rumors were flying that the library was inundated with applications for this position, some of them from manifestly unqualified candidates. Brainin underscored the continuing need for a full-time Division chief who was fully grounded in traditional Jewish texts and knowledgeable about Hebrew and Yiddish literature – someone who would be dedicated to serving the Jewish Division’s clientele. These were points that he had raised in a face-to-face meeting with Gottheil.

Brainin then turned his sights to the legacy of the Jewish Division’s recently deceased chief. “To tell the truth, the Jewish Division of the New York Public Library always gave the impression of being a stepchild or an orphan,” he wrote. “Everything in the Division was neglected, almost chaotic. To this day it lacks a catalog. While Freidus was alive he wanted to serve as a living catalog, without which no one could cope.” Visitors to the Jewish Division were utterly dependent upon Freidus’s whims because “only he knew which Jewish books are located in his department and where they are shelved, and which ones are lacking.” He insisted upon “never giving out the books that one needed or requested, but rather those books that he wanted and considered necessary.” This was a situation that was “impossible in any other library.” Moreover, the ambience of Room 217 “lacked quiet and orderliness,” Brainin continued. “The entire Jewish Division took on the features of a kind of kloyzl, a yeshiva of bygone times.” With Freidus now dead and buried, the time had come “to demand that the Jewish Division of the New York Public Library be managed properly, that its faults be addressed, and that the next librarian be up to the task.” Brainin summed up the Freidus legacy as one of “neglect and impossible management.”

Brainin’s harsh appraisal of the Jewish Division’s deceased chief seems like a slap in the face, considering that he was among the select few who, only six years earlier, had been honored with an invitation to Freidus’s surprise fiftieth birthday party. The article gives no hint about what caused him to sour on the Freidus legacy.

One month later, Brainin’s article met with a resounding rebuttal by the lawyer and American Jewish historian Samuel Oppenheim 11 11 Huhner, Leon. “Samuel Oppenheim.” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society, no. 32 (1931): 132-34. Accessed September 23, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43059648. Oppenheim’s papers are at the American Jewish Historical Society: https://archives.cjh.org//repositories/3/resources/1657. (1857-1928), in the same newspaper’s English section. 12 12 Samuel Oppenheim, “The Jewish Section of the Library: A Rejoinder to Mr. Reuben Brainin’s Article on the Jewish Section of the 42nd Street Library and the Late Mr. Abraham S. Freidus, Its Administrator,” in Der Tog (The Day), New York, January 20, 1924. Accessible online via the Historical Jewish Press Project / JPress. “I brand the Brainin statement as utterly at variance with the facts,” Oppenheim wrote. The Jewish Division lacks a catalog? “This statement is absolutely without the slightest foundation, as any one who has visited the Jewish room can testify. There is and always has been a catalogue there. I myself have used it frequently in the Fifth Avenue building since 1911, and so have others. Mr. Brainin’s statement is made out of whole cloth.” Not only did the Jewish Division have its own catalog, but “there is also the main catalogue in room 315 which lists all the Jewish books among the other books in the library.”

Regarding Brainin’s characterization of Freidus as a “living catalog”: “This is no crime but a merit.” Freidus “gave his personal attention and helped in every way to solve all kinds of problems without loss of time to those who are not intimately acquainted with the true sources of information.”

Oppenheim scorned the accusation that the Jewish Division resembled a kloyzl, a traditional Jewish study house. Admittedly, the Division was in “cramped quarters” in Room 217—and “the sound of requests made to the librarian for books and information would naturally, in a small room, be carried to readers, but on any complaint Freidus would command silence.” (Borokhov, too, had referred to the “quiet confines of the Jewish Division” in his 1917 article.) And perhaps equally to the point, “the appearance of the Jewish room which was frequented in the main by Jews… naturally did not present the appearance of a Catholic resort, or a quaker [sic] meeting place, a Presbyterian synod house or a Joss House attendance, but of a Jewish room where friends and acquaintances often met and asked each other for information on the subjects in which they were interested.”

In a curious mixture of gendered praise, Oppenheim compared Freidus’s attentiveness to “a loving mother looking after the welfare of her children… It needed a man like Freidus to supply the wants of students and writers, and their calls for help and mental food and clothing were not neglected” (my italics). (Others, including Borokhov, referred to the otherwise childless Freidus as the Jewish Division’s father.) In short, what Brainin viewed as Freidus’s shortcomings, Oppenheim considered to be that librarian’s most admirable and essential qualities. Decades later, a subsequent chief of the Jewish Division, Leonard Singer Gold, agreed: “Thus, the man whom Reuben Brainin accused of not knowing how to run a library actually left behind him a firm foundation upon which his successors could build… We must conclude that this lonely, eccentric person, who invested all his life force in The Library and who could reach out to his fellow man only through The Library, finally succeeded in wresting his greatest contribution from his most apparent shortcoming.

13

13

Gold, Leonard Singer. “Abraham Solomon Freidus.” Studies in Bibliography and Booklore, vol. 10, no. 3/4 (Winter 1973/74): 72. Accessible online via JSTOR.

Der kibetser December 15, 1911.

The East Side bookworm: Mr. Freidus of the Astor Library. Founded in 1897, the Jewish Division was originally situated in the building of the Astor Library (now the home of The Public Theater), which had recently been incorporated into the New York Public Library. In 1911, NYPL relocated the former Astor Library’s departments and collections to its newly constructed library at Forty-Second Street Library and Fifth Avenue:

“Oh, how slipshod and careless people act with books. Yesterday I gave out a book for the first time, a brand-new one, and today I already find a hole in page 59 and, oddly enough, exactly the same hole in page 60.” (Artist: “Sam.”)

The Model Jewish Library: Transformations and Continuities

Although he was a habitué of Yiddish lecture halls and a regular at the Yiddish theaters of New York, Freidus was no Yiddishist. Still, among the more unexpected finds that came my way during this project were three caricatures of Freidus from the Yiddish press. Two of these, generously provided by librarians in NYPL’s Dorot Jewish Division, appeared in the Yiddish humor magazines Der groyser kundes and Der kibetser (both in 1911); a third, which I found through JPress, was from the newspaper Der tog (dating from 1922). The caricatures in the Kundes and Kibetser depict Freidus in the workplace, scissors at the ready. The one in Der tog, which accompanies a journalist’s account of watering holes on New York’s Lower East Side, shows Freidus dozing off at a small table at the Café Royal, opposite a young woman who has evidently not caught his eye.

![<p>Irritating personality [<em>Spodik-dreyer</em>], no. <span class="numbers">50</span>.</p>

<p><em>Der groyser kundes</em>, March <span class="numbers">8</span>, <span class="numbers">1911</span>.</p>

<p>The celebrity with whom we conclude our series of irritating personalities is our friend, your friend, the books’ friend, <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>the man with the shears,” Mr. Freidus, Librarian of the Jewish Division of The New York Public Library — the only man in the neighborhood who is <em>not</em> irritating. (Artist: Saul Raskin.)<br></p>](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ingeveb/images/groyser-kundes.jpg)

Irritating personality [Spodik-dreyer], no. 50.

Der groyser kundes, March 8, 1911.

The celebrity with whom we conclude our series of irritating personalities is our friend, your friend, the books’ friend, “the man with the shears,” Mr. Freidus, Librarian of the Jewish Division of The New York Public Library — the only man in the neighborhood who is not irritating. (Artist: Saul Raskin.)

Encountering these caricatures of a librarian in the popular Yiddish press gave me pause. As far as I’m aware, no Judaica librarian among my contemporaries has been immortalized by a cartoonist’s ink nib. Yet Avrom-Zalmen Freydus, aka Abraham S. Freidus, was represented in the Yiddish newspapers and magazines of his era as a familiar public figure, foibles, warts, and all – something that would be almost inconceivable for his librarian counterparts in today’s media environment. For better or worse, the time has passed when caricaturists targeted Jewish librarians.

This observation prompts some reflections about the position of Jewish librarians in that “heroic age,” a century ago, of library collection building and systematizing in the United States. It was an era as well of widespread and intense political activism. More than once, the confirmed socialist Borokhov expressed his admiration for the Jewish bankers and lawyers whose contributions enabled America’s Jewish libraries to acquire and manage world-class collections. The leading Jewish philanthropists of the early twentieth century considered it a matter of social and communal prestige to endow book funds and donate incunabula to those institutions. Today’s high-profile Jewish business moguls — whether on Wall Street, in Silicon Valley, or in Hollywood — seldom shower their ostentatious largesse on the country’s great Jewish libraries, at least not to the extent that their predecessors, such as Jacob Schiff and Louis Marshall, once did.

Nevertheless, Ber Borokhov’s formula for the model Jewish library — “Talmudic acuity and the most precise classification, genuine Jewish warmth and an insistent manner of service that is authentically Jewish” — lives on in the U.S., Israel, and elsewhere, albeit transmuted in style, technology, and funding structures. If Borokhov were to somehow rise from his grave near the Sea of Galilee, in the Kinneret Cemetery (where his remains were moved from Kiev in 1963), and pay a visit to Jerusalem, he would find himself entirely at home in the Sifriyah le’umit – the National Library of Israel (NLI).

14

14

The NLI is currently located on the Hebrew University’s Givat Ram campus and is scheduled to move to its new building next to the Knesset and opposite the Israel Museum in 2022.

Although the NLI operates on a vastly grander scale than did Freidus’s bailiwick, in-person visitors to the Jerusalem library on Giv’at Ram are bound to encounter something of the kloyzl atmosphere that Reuven Brainin so disdained in his visits to Room 217 of the Forty-Second Street Library. (Whether the NLI’s “kloyzl atmosphere” will migrate to its new building, which is scheduled to open in 2022, remains to be seen.) Simultaneously, the NLI’s collections are expertly cataloged and classified according to international standards – like those of the NYPL in Freidus’s day. In addition, researchers worldwide have ready access to the vast array of resources that the NLI puts at our disposal, some of which I tapped into from my home in California while working on this article. That marks a quantum leap from the time when the library was a destination one had to visit in order to tap the information shelved within — apart from the occasions when you ran into the librarian at the Café Royal and were handed a sheaf of newspaper clippings.

In the century that has passed since Freidus was the custodian of NYPL’s Jewish Division, research librarianship has evolved from a skilled artisanal craft into a technocratic profession, and the “national library of the Jewish people” (as the NLI sometimes styles itself) has likewise undergone this transformation. Over the past several decades, Israel’s national library has developed its state-of-the-art information infrastructure in a business collaboration with the Israeli firm Ex Libris, and since 2000, that same company has successfully marketed its technology to libraries around the world. In a twist of the dialectic that a Marxist like Borokhov might well have appreciated, a few years ago Ex Libris was bought out by an American library-technology conglomerate, ProQuest, headquartered in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and owned by a private investment firm based in New York City: a blending of Israeli technical prowess, American corporate oligopoly, and Wall Street private equity. Borokhov would likely have marveled at the ironies of late capitalism, while at the same time grasping that the amalgam of organizational methods, advanced technologies, and service ethos that drive today’s libraries, Jewish and otherwise, had its roots in systems devised by librarians like Freidus over a century ago.

![<p><em>Der tog </em>(<em>The Day</em>), June <span class="numbers">11</span>, <span class="numbers">1922</span>.</p>

<p>Freidus at the Café Royal: In her eyes, she’s dreaming a dream, and in his eyes, sleep has snuck in. (Artist: Yehude <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>Usa” Gombarg, accompanying the article by Tsvi-Hersh Rubinshteyn, <span class="push-double"></span><span class="pull-double">“</span>A shpatsir iber der barihmter idisher <span class="push-single"></span><span class="pull-single">‘</span>teater gas’ fun unzer ist sayd” [A Stroll Through the Famous <span class="push-single"></span><span class="pull-single">‘</span>Theater Row’ of Our East Side.”])<br></p>](https://s3.amazonaws.com/ingeveb/images/Freidus-by-Gombarg-Tog-1922.png)

Der tog (The Day), June 11, 1922.

Freidus at the Café Royal: In her eyes, she’s dreaming a dream, and in his eyes, sleep has snuck in. (Artist: Yehude “Usa” Gombarg, accompanying the article by Tsvi-Hersh Rubinshteyn, “A shpatsir iber der barihmter idisher ‘teater gas’ fun unzer ist sayd” [A Stroll Through the Famous ‘Theater Row’ of Our East Side.”])

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the assistance of Lyudmila Sholokhova and Amanda Miryem-Khaye Seigel of the Dorot Jewish Division of the New York Public Library, who have shared materials — and enthusiasm — about Abraham S. Freidus and the early years of the Jewish Division. Many thanks, as well, to Vanessa Freedman, Hebrew and Jewish Studies Librarian at University College - London, for providing a PDF copy of her 2010 M.A. dissertation.